Good Assessment

Practitioners’ Handbook

Second edition

www.researchinpractice.org.uk

2

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

2

Good Assessment:

Practitioners’ Handbook

Assessment is a central part of adult social care, both as a gateway

to support and as an intervention in its own right. Good practice

in assessment is essential in order to improve the experience and

outcomes of adults and carers, to meet the expectations of law and

policy, and to enable care and support planning that uses resources in

the most effective way.

This handbook is designed to

enable you to:

> Understand adults’ and carers’

experience of assessment.

> Identify how the context of adult social

care affects your assessments.

> Understand the purpose of assessment.

> Use legal literacy to underpin your

assessment practice.

> Follow the steps that lead to

good experience and outcomes in

assessment.

> Develop the capabilities and

understanding to be a good assessor.

> Receive good support for assessment.

This handbook is aimed at practitioners who

are carrying out assessments and those who

support them, including first-line managers

and practice development staff. Practitioners

who are undertaking assessments will have

different levels of experience and professional

development, so the handbook is divided into

different sections to make it easier for people to

identify those elements that are likely to be most

useful for them.

The handbook concentrates on Care Act 2014

assessment for care and support for adults,

and support for carers. In the Care Act 2014,

assessment precedes eligibility, and care and

support planning. The handbook explores

assessment practice in its own right, whilst also

making reference to what happens following

assessment.

The handbook makes links to mental capacity

assessments and safeguarding enquiries. Adult

social care practitioners may be involved in other

assessments, for example, occupational therapists

completing assessments for major adaptations

funded by Disabled Facilities Grants under the

Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration

Act 1996, or Approved Mental Health Professionals

completing assessments under the Mental Health

Act 1983. The same principles of assessment apply.

The information and tools in this handbook

can be used by adults and carers, and by their

advocates, to support them when they are having

assessments. They may also be useful to people

working in other agencies such as health, housing

and the community voluntary and social enterprise

sector.

Introduction

3

©Research in Practice September 2022

3

2

This edition

The first edition of this handbook came out of a

Research in Practice for Adults Change Project

called Ensuring effective assessment on the

front line, which brought research and practice

together to look at how best to ensure good

assessment in adult social care. The focus was

on supporting people to carry out assessments

that are consistently empowering and useful.

The handbook also drew on learning from a

Research in Practice Change Project in Children’s

Services called Analysis and Critical Thinking in

Assessment (Brown et al., 2014).

The handbook has been more recently reviewed

with input from Research in Practice Partners

in order to reflect the changing landscape

of assessment practice. This second edition

includes updates relating to guidance, evidence

from the implementation of the Care Act

2014, developments in practice and practice

standards. It also refers to and signposts

additional Research in Practice resources.

At the time of writing the second edition, the

major practice themes in adult social care

were equality, diversity and inclusion, and

co-production. The focus in practice was on

strengths-based work and relationship-based

practice and the importance of a human rights

approach to adult social care. The handbook

was revised after a year of practising during

the COVID-19 pandemic and so also reflects

emerging practice arising from this, particularly

relating to virtual assessment.

Language

Throughout the handbook, the aim is to use

clear and accessible language. People who are

being ‘assessed’ are referred to as ‘adults’ and

‘carers’ as this is what they are called in the Care

Act 2014, unless the handbook is referring to

evidence that uses another term. The Act talks

about ‘care and support’ for adults and ‘support’

for carers. We use ‘care and support’ throughout.

The word assessment itself is problematic.

Research in Practice Partners (2021) identified

that the word ‘assessment’ is now being

used less often and replaced by the word

‘conversation’. This is because ‘assessment’

can feel bureaucratic or like a test. However,

it is important to remember that assessment

has a meaning in law. In this handbook, we use

assessment to reflect the language of the Care

Act 2014.

4

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

4

Overview of the handbook

The handbook sets out good practice in assessment based on evidence including

research, practice experience and the lived experience of adults and carers. It

considers the quality of experience as well as the outcomes of assessment.

The handbook starts with a brief overview of the context for assessment in adult

social care, the purpose of assessment and the law that underpins it, and adults’ and

carers’ experience of assessment.

The handbook then explores three

areas:

1. Good assessment

This highlights ethics of assessment

and approaches that underpin good

assessment. The handbook sets out a series

of steps to carrying out a good assessment,

and specific elements of assessment that

need to be considered.

2. Good assessors

This looks at who should do assessments,

the capabilities that they need, and the

impact of different types of situations on

the capabilities required.

3. Good support for assessment

This looks at the support that is required

for assessors to do good assessments,

including learning and development, and

organisational support.

Overview

5

©Research in Practice September 2022

5

4

Using the handbook

Practitioners and those who support them work in busy environments. The handbook

aims to act as a reference. It can be downloaded and easily searched using the

contents page or search function. Individual pages can be printed. The tools are also

available in a form that can be edited, so that you can write onto them directly.

Throughout, there are highlighted

areas:

Main message

These are short summaries of the main

learning from the section in which they are

placed.

Reflective point

These are designed to prompt reflection on

how you can transfer the learning into your

practice.

Exercise

These support you to use the learning to

think about your own practice.

Good practice suggestion

These suggestions have emerged from the

evidence and are designed to be used to

promote discussion and reflection.

Example

These help you consider how to use the

learning in your practice.

Signposting

This signposts you to further Research in

Practice resources.

ee.gg.

Learning needs analysis

You can use the Learning needs analysis on

pages 8 to 9 to rate your current capabilities

– how you act to use your knowledge,

skills, behaviour and values in practice – for

each area of assessment practice that the

handbook covers. This will support you to get

the most out of the handbook by focusing on

the areas that you want to develop.

Following the Learning needs analysis, there

is a Learning and development plan that

you can complete as you use the handbook.

This supports you to transfer your learning

into practice, so that it impacts positively on

the experience and outcomes of adults and

carers.

Using the handbook

6

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

6

Contents

1. Learning needs analysis - page 8

2. Learning and development plan - page 10

3. Context of assessment - page 11

> Context of assessment in adult social care -

page 11

> The purpose of assessment - page 13

> Legal literacy: Assessment for Care and

Support - page 18

> Legal literacy: Links to other assessments -

page 23

> Adults’ and carers’ experiences - page 25

4. Good assessment - page 27

> Ethics and approaches to assessment -

page 28

> Person-centred approach - page 28

> Relationship-based practice - page 29

> Strengths-based practice - page 29

> Human Rights approach - page 30

> Anti-oppressive practice - page 31

> Ethics of care - page 31

> Confidentiality and consent - page 31

> Assessment steps - page 32

- Step 1: Building a relationship - page 34

- Exercise: Understanding responses to

assessment - page 37

- Step 2: Gathering information - page 39

- Exercise: Ecogram - page 41

- Step 3: Analysing the information - page

42

- Exercise: Important to, important for -

page 45

- Step 4: Making a judgement - page 46

- Exercise: Discrepancy matrix - page 49

> Action and review - page 50

> Supported self-assessment - page 52

> Joined-up assessment - page 53

> Methods of assessment - page 55

5. Good assessor - page 58

> Assessment capabilities - page 58

> Consideration of complexity - page 61

> Specific considerations: - page 63

- Carers - page 63

- Older people - page 64

- People with learning disabilities - page 65

- Autistic adults - page 65

- People with an acquired brain injury - page

65

- People with hearing and visual

impairments - page 65

- People living with dementia - page 66

- People with multiple complex needs - page

66

- People in prison - page 66

- People at end of life - page 67

- Young carers - page 67

- Young adults - page 67

> Recording assessment - page 69

> Practitioner audit - page 72

6. Good support for assessment - page 74

> Professional development - page 74

> Critical reflection - page 77

> Organisational support - page 79

Conclusion - page 83

References - page 84

Contents

7

©Research in Practice September 2022

7

6

Learning needs analysis

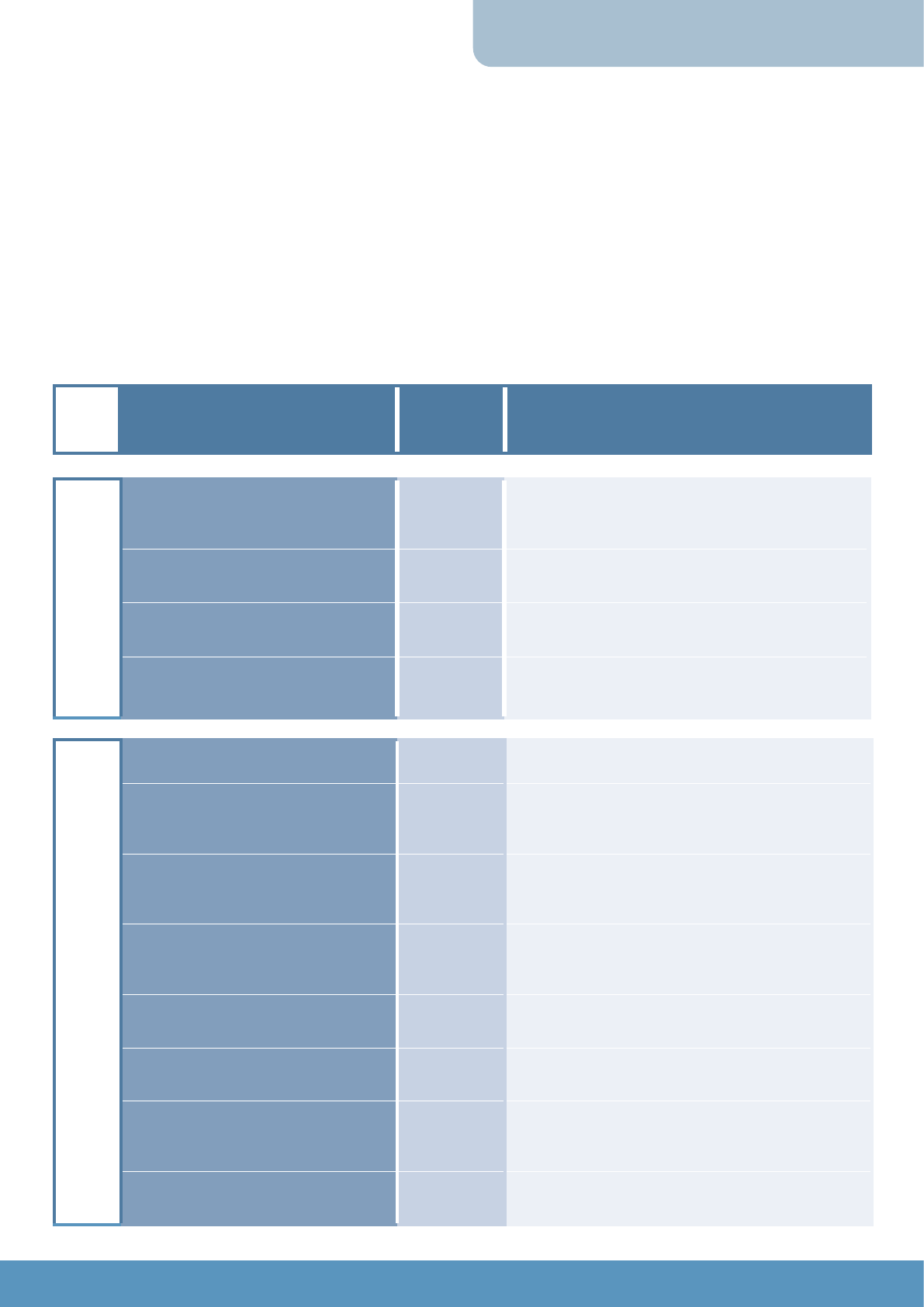

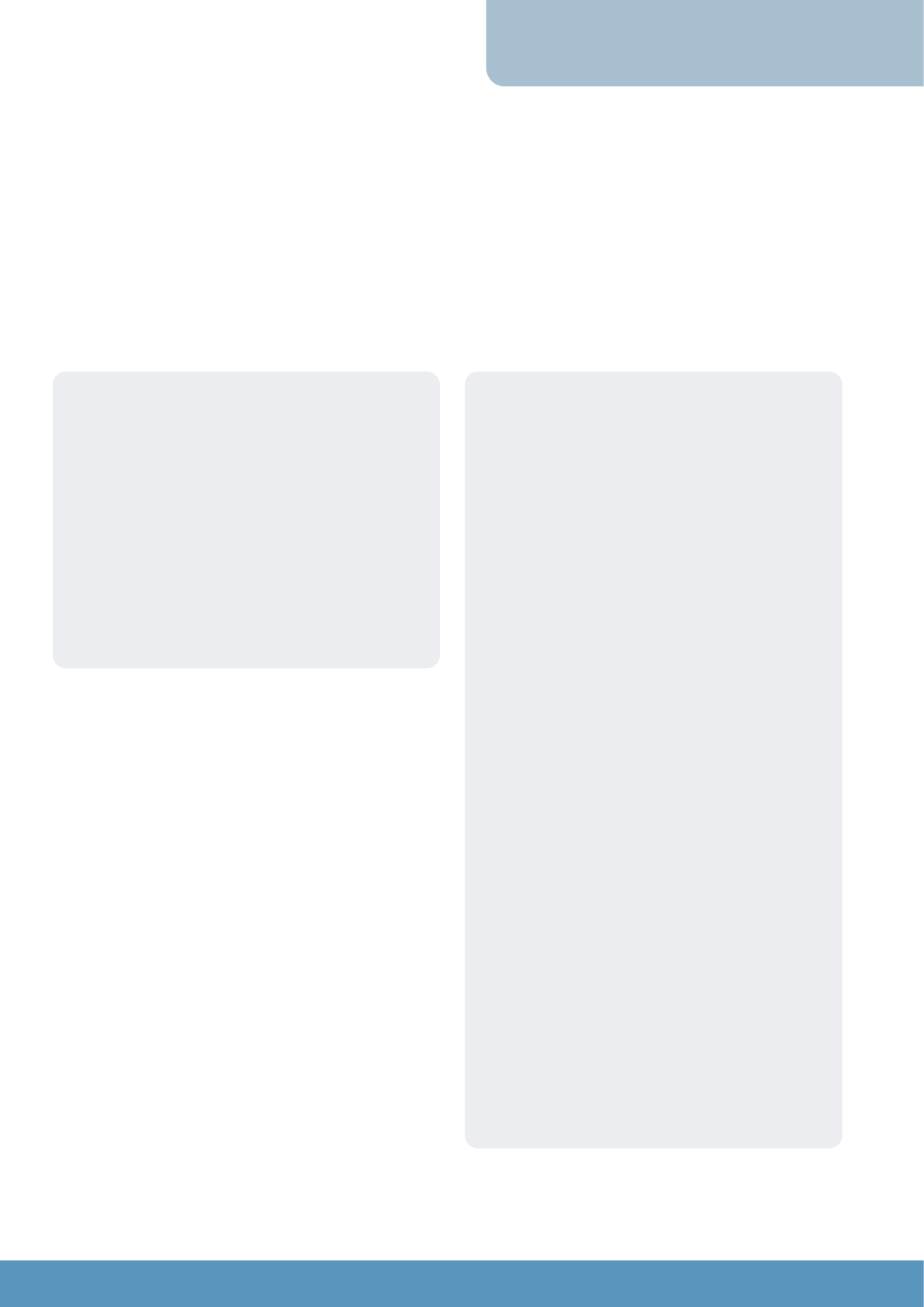

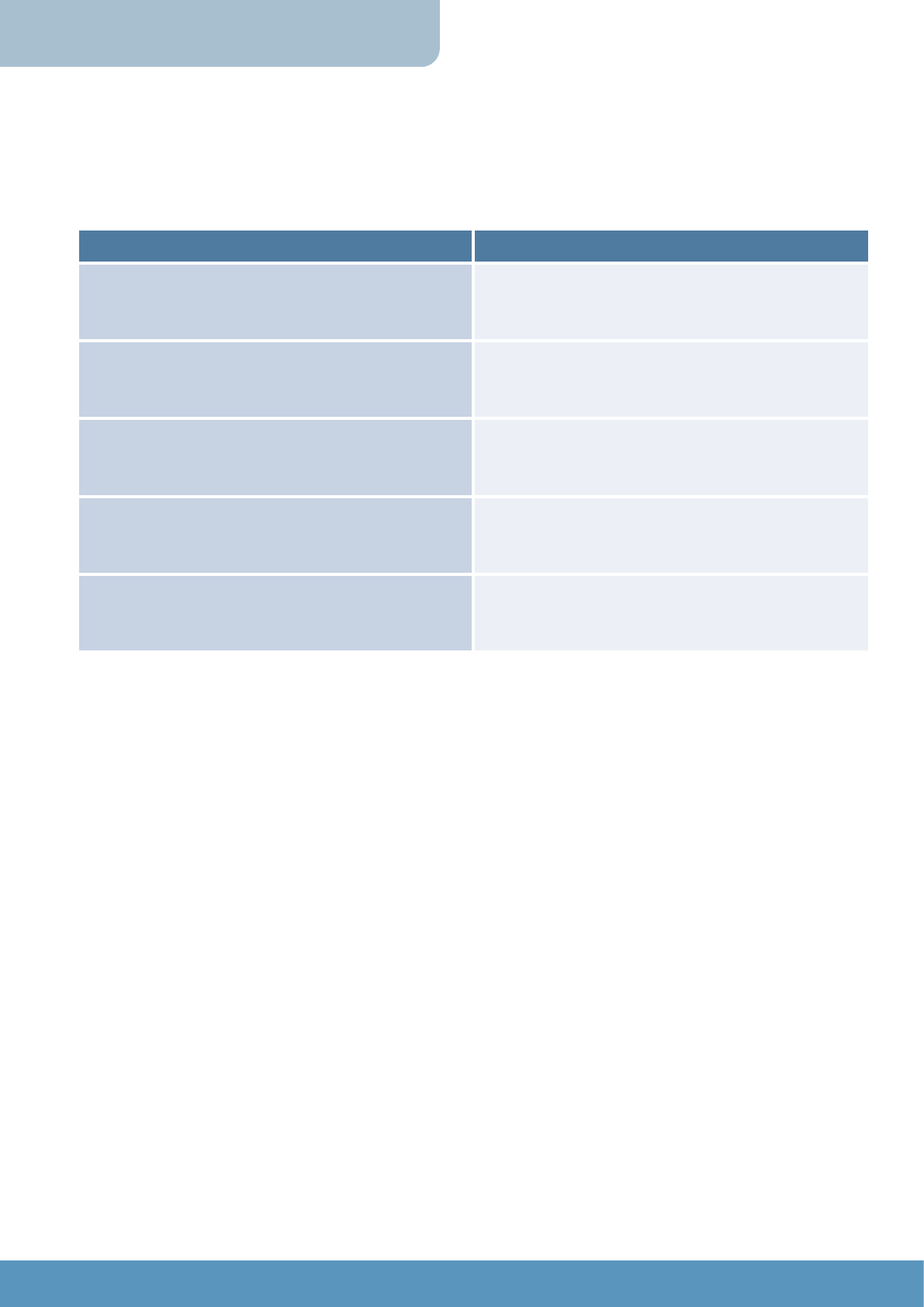

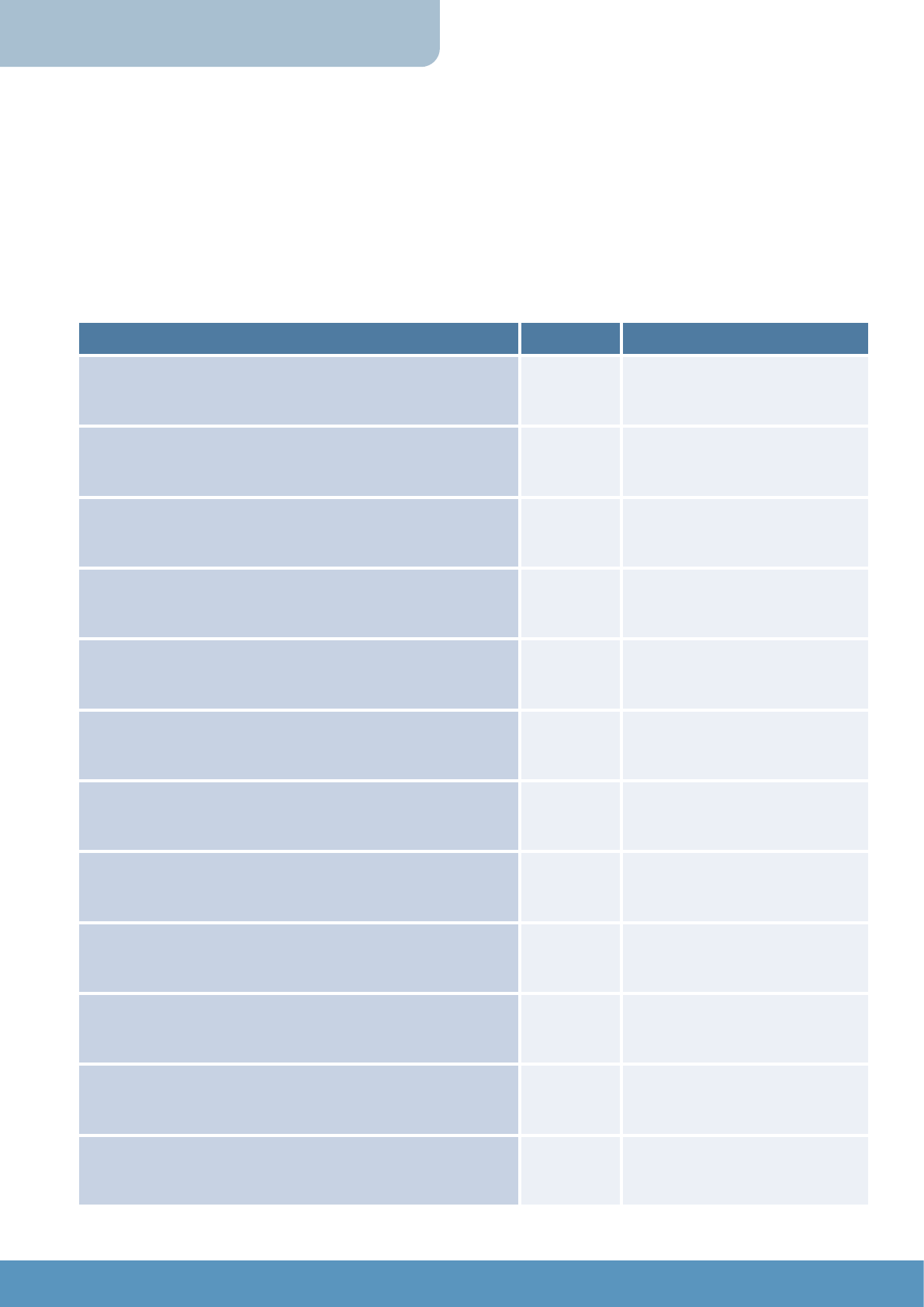

1. Learning needs analysis

The learning needs analysis allows you to rate your capability for each area of assessment practice that is

covered in this handbook. This feeds into a learning and development plan to help you address the areas

that you rate as low.

You can use the handbook to support your learning and development in order to meet your practice

development goals. When you have met your goals, you can revisit the needs analysis to see how your

ratings have changed.

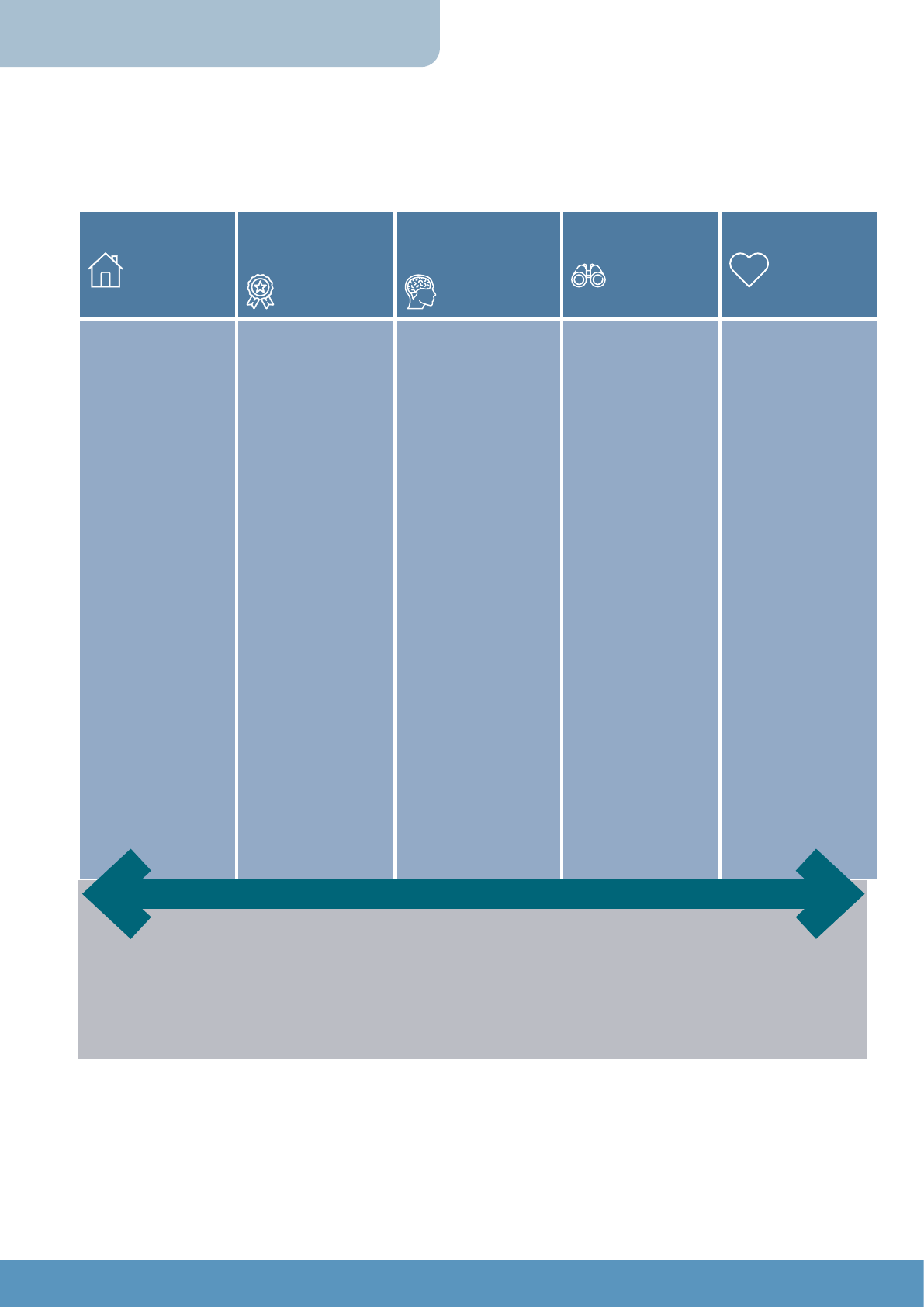

Area Capability Capability

level (1–5)

Comments – evidence of good practice or

areas for development from feedback, practice

examples or reflection

Context

I understand the context of

assessment and how that impacts

on my assessment.

I understand the purpose of

assessment and my role in this.

I understand the legal framework for

assessment.

I know what adults and carers want

from assessment.

Good assessment

I carry out ethical assessments.

I am able to build relationships

with adults and carers to support

assessment.

I am able to gather appropriate and

proportionate information about a

situation.

I am able to analyse information

to understand the meaning of a

situation.

I am able to make defensible

judgments based on my assessment.

I support people to do self-

assessment.

I carry out joint assessments with

other agencies and organisations for

the benefit of adults and carers.

I use a range of methods of

assessment to enable involvement.

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

8

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

8

Area Capability Capability

level (1–5)

Comments – evidence of good practice or

areas for development from feedback, practice

examples or reflection

Good assessor

I understand the values, knowledge

and skills that underpin good

assessment.

I record assessments in ways that

empower adults and carers, and

promote their wellbeing.

Good support

I continually develop my capabilities

for assessment.

I critically reflect on the experience

and outcomes of my assessments.

I seek the appropriate support for

assessments.

I contribute to organisational

learning about assessment.

Example

Jade is a newly qualified social worker. She was asked to reflect on a recent conversation

with an older person. Jade used the learning needs analysis to consider her assessment

capabilities based on what happened in the conversation. She then discussed this with her

supervisor and wrote up the reflection and discussion for her portfolio.

ee.gg.

Learning needs analysis

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

12345

9

©Research in Practice September 2022

9

8

Learning & development plan

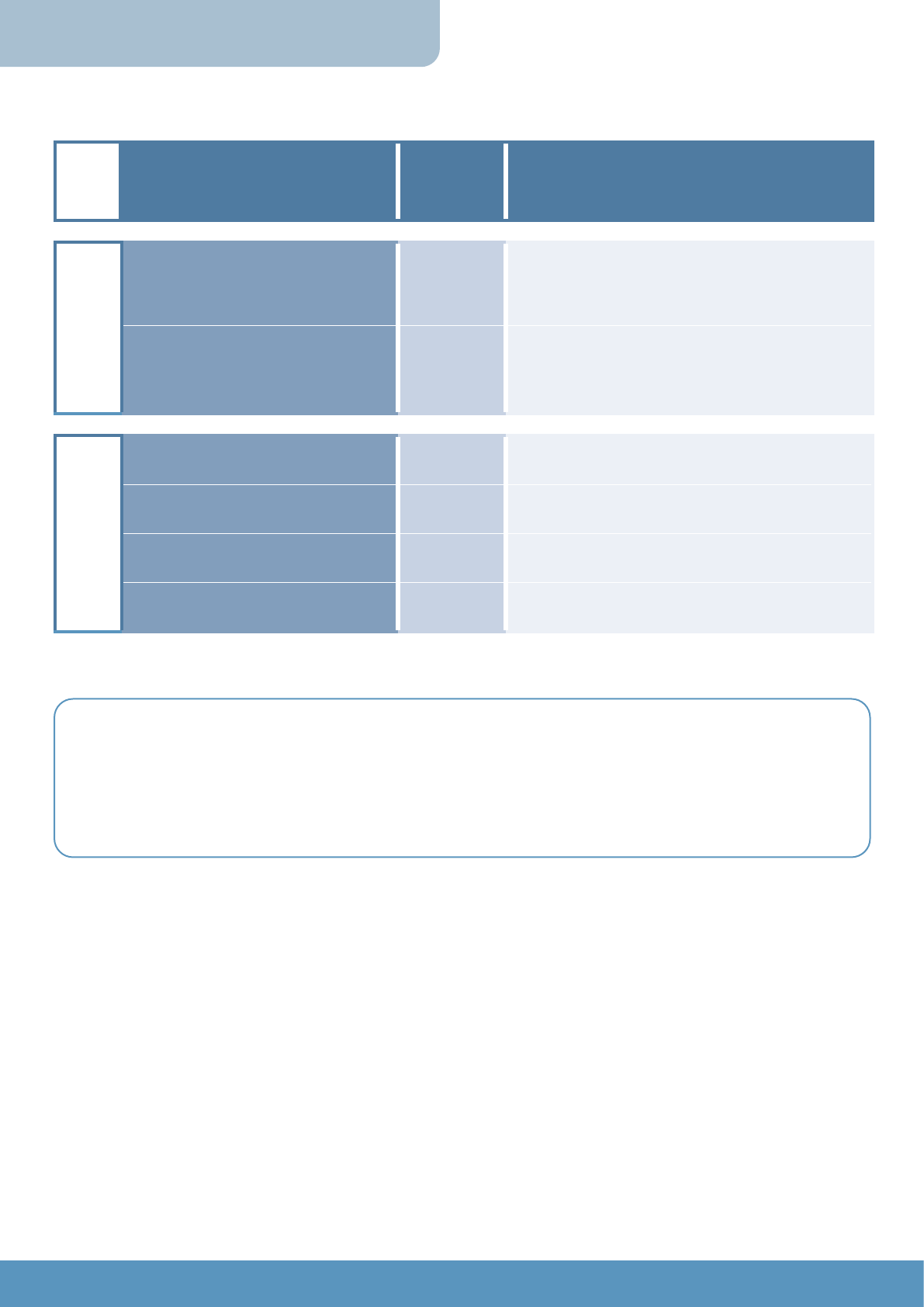

2. Learning and development plan

Area of practice

(taken from learning needs

analysis)

Practice goal

(what you want to do

differently)

Actions

(to achieve goal)

11

©Research in Practice September 2022

11

10

3. Context of assessment

in adult social care

The approach we took … was to put

assessments at the centre of the legal

framework for adult social care …. It operates

both as a service in its own right, and as

the gateway to the provision of services.

Furthermore, assessment is instrumental –

along with the eligibility framework and care

planning – in determining the scope of adult

social care in practice.

(Law Commission report on Adult Social Care,

2011, p. 25).

Assessment is a central part of adult social care.

The Care Act 2014 affirmed assessment as both

the gateway to care and support as well as being

an important experience in its own right. This

reflects the significance of the decisions and

actions that assessment leads to and the impact

that assessment can have, both positive and

negative, on the lives of adults and carers.

Assessment needs to balance two central values:

> Autonomy – supporting people to make

their own decisions and to pursue their

wellbeing.

> Fairness – ensuring that resources are

distributed according to need and to

achieve outcomes.

Before the Care Act 2014 was introduced, the

Law Commission’s consultation with adults and

carers identified areas that needed to change.

These included:

> lack of clarity about what assessment is

> screening people out of assessments who

would benefit from an assessment

> not involving people fully in assessments

> concentrating on needs and problems,

rather than on abilities and aspirations

> delays in getting an assessment

> multiple assessments and duplication of

assessments

> different assessment practice leading to

different decisions on care and support

around the country

> assessments being driven by the resources

available

> assuming that carers will be willing and

able to care

> changes in care and support if people move

between services, e.g. from Children’s to

Adults’ Services

> changes in care and support if people move

house.

(Law Commission, 2011)

Context of assessment

in adult social care

12

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

12

As a result, the Care Act 2014 aimed to make

assessment practice more transparent and

consistent. The changes in the law required

assessors to work differently because of the

overarching duties: to promote wellbeing; to

reduce, prevent and delay needs; to integrate

care and support; and to provide information and

advice.

Assessment takes place within the context of a

complex and changing landscape. Since the Care

Act 2014 was enacted, England has seen ongoing

social and economic change. Implementation

of the Act has taken place against a backdrop

of austerity in public services, and the impact

of funding shortages has been exacerbated by

the COVID-19 pandemic (ADASS, 2020). The

pandemic has also highlighted disparities in risk

and health related to inequalities of income,

housing and occupation. Those inequalities may

be underpinned by issues of discrimination, in

particular due to racialisation (Public Health

England, 2020). Throughout this period there

has also been widespread technological change,

including growth in the use of social media and

digital technology.

Adults and carers have had a growing voice, and

have advocated for co-production, that is to have

equal say and involvement in designing services

and in individual assessment (for example, TLAP,

2018).

Main message

Assessment under the Care Act 2014 aims

to empower and involve adults and carers.

Reflective point

How do you talk transparently

with adults and carers about the

opportunities and constraints of

assessment?

Signposting

Nosowska and Series (2013). Good

decision-making: Practitioners’

handbook. Research in Practice

Context of assessment

in adult social care

13

©Research in Practice September 2022

13

12

The purpose of

assessment

The Research in Practice brief guide to

assessment, which is written for the general

public, explains what an assessment is.

An adult social care assessment is a

process which identifies what you want

to achieve in order to maintain or improve

your wellbeing, whilst having as much

independence and control over your day-

to-day life as possible. The things you want

to achieve that support your wellbeing

are often referred to as your ‘individual

outcomes’. … Under the Care Act 2014, your

local council has a duty to carry out an

adult social care assessment with anybody

they are aware of who seems to need care

or support. (McNamara, 2018, pp. 2–3)

The Research in Practice brief guide for

carers says:

The Care Act 2014 gives carers a legal right

to an assessment of their needs (regardless

of how much care they provide) and suitable

support to help them in their role as a

carer. This assessment of need is usually

done by the local authority, or a voluntary

organisation working on their behalf. Even

where carers are not eligible for funded

support, councils have a duty to provide

information and advice to carers. The Care

Act has improved rights for carers and

means that a carer’s eligibility for support

may have changed. … Carers are entitled to

an assessment even if the person they care

for does not receive support from the local

council. (Bishop, 2016a, p. 2)

The rights set out in the Care Act apply to

adult carers (over the age of 18) and young

carers (aged under 18) who are caring for

someone over 18. For young carers and

adults who care for disabled children,

assessment and support is also guided

by children’s law and practice. When a

professional is assessing a carer’s needs

and those of the person they care for, the

Care Act says that the circumstances

of the whole family should be taken into

consideration so that the support a family

receives is as joined up as possible. This

includes making sure the needs of any

young carers in the family are included. The

assessment will look at the carer’s physical,

emotional and mental wellbeing, and what

support might be needed to maintain it. (p.

3)

Context of assessment

in adult social care

14

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

14

Section 1 of the Care Act 2014 states, ‘The general

duty of a local authority, in exercising a function

under this Part [Care and support] in the case of

an individual, is to promote that individual’s well-

being.’ This means that assessment is ultimately

undertaken to promote wellbeing.

The Change Project Development Group

(Research in Practice for Adults, 2014) identified

the overarching purpose of assessment as

maintaining or improving quality of life. They also

identified a series of aims that underpinned this

overarching purpose:

> identifying the need behind the assessment

> managing crisis

> building a relationship

> sharing information and advice

> co-producing a picture of needs, risks and

strengths

> gathering evidence for analysis

> making a judgment, including managing risk

> identifying outcomes, priorities and goals

> ensuring appropriate level of care and support

> maintaining/improving quality of life.

Throughout this, assessors need to be able to show

transparency in their thinking and decision-making.

There is also an organisational need to gather

information about the assessment to inform service

development and improvement.

The Care Act 2014 statutory guidance (first

published in October 2014 and last updated in April

2021) states that assessment ‘should not just be

seen as a gateway to care and support, but should

be a critical intervention in its own right’ (DHSC,

2021a, para. 6.2). Ultimately, assessment should be

an empowering experience that helps someone to

understand their situation and access the support

that they need to achieve outcomes. This has an

ethical element, including the promotion of people’s

human rights. An individual assessment is not an

isolated activity, however; the assessment of one

person must always be balanced with the needs

and rights of others, including how resources will be

shared.

Assessment has a number of stakeholders and the

purpose of assessment may be different for each of

them. They will each bring different views and values

to bear on the assessment.

Context of assessment

in adult social care

15

©Research in Practice September 2022

15

14

The Change Project Development Group (Research

in Practice for Adults, 2014) identified the following

stakeholders and their considerations:

> Adult or carer – human rights, outcomes, life

experience, wellbeing, being heard, appropriate

support.

> Carer of adult being assessed – know needs will

be met, acknowledgement, information, reduce

stress, advice.

> Assessor – professional integrity for the work

that you have completed, doing the best for

people.

> Family – support, being listened to, information,

assurance that needs are being met.

> Organisation – meet legal duties, target

resources, provide outcomes, facilitate

prevention of care and support needs.

> Other professionals/agencies – information,

support for decisions.

> Providers – meeting needs in way person wants,

information for support planning.

> Commissioners – developing the market to

provide choice, identifying gaps.

> Wider community – concern about risks to

adults, carers and others.

Ultimately, assessment is a balance between what

the person being assessed needs and wants, and

what is possible – in terms of their strengths, network

and community, and the resources available. The

goal of assessment should be to support people to

understand their situation so that they can make

their own judgments about what is needed and make

decisions and take actions to achieve what’s needed.

But this may be constrained by the level of capacity a

person has to take a lead in this process; that ability

may be affected by:

> An impairment that affects their capacity,

in which case the Mental Capacity Act 2005

should be followed.

> Difficulties with being heard, in which case

advocacy should be considered.

> The effects of life circumstances, in which

case an empowering relationship may help to

overcome the barriers.

Main message

The ultimate purpose of an

assessment is to promote wellbeing.

Reflective points

> How do you explain

assessment to adults and

carers?

> How do you balance the

principles of autonomy

(supporting someone to

have choice and control) and

fairness (ensuring equality

of access to resources) in

assessment?

Good practice

suggestion

Look at a recent assessment made

by you or a colleague has done.

Identify how the assessment

empowered the person being

assessed.

Signposting

McNamara (2018). Assessment: Brief

Guide. Research in Practice

Bishop (2016a). What rights do carers

have to an assessment of their needs?

Brief guide. Research in Practice

Context of assessment

in adult social care

16

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

16

DO

> Come prepared, having read the

notes.

> Be honest, show empathy and listen

carefully.

> Be friendly and professional so I can

trust and have confidence in you.

> Explain what a carer’s assessment

is (that it’s about my needs, not an

assessment of my caring ability).

> Prioritise the person I care for and

make sure you listen to them.

> Find out about the situation on a

bad day – to understand fluctuating

needs.

> See me as an asset, part of a support

network helping to support the

person I care for.

> Be knowledgeable of services and

suggest options that might help.

> Talk about what can be done, rather

than what can’t.

> See beyond me as just a carer.

> Give me a contact number and a

name of a person I can get hold of.

> Write a summary of what has

happened so that other people can

prepare themselves before visiting.

DON’T

> Appear to be or be in a rush.

> Use jargon or buzzwords (in writing or

speaking).

> Make assumptions about what I like

or can do.

> Be afraid of saying ‘I’ll get back to you

as I don’t know the answer.’

> Make promises you can’t keep.

> ‘Signpost’ me endlessly with no result

– help me use the information that

you can give me.

The Social Work Practice with Carers’ project (www.carers.ripfa.org.uk) identified top

tips for assessors:

Top tips for assessors

Context of assessment

in adult social care

17

©Research in Practice September 2022

17

16

BASW and Shaping Our Lives developed

a charter for disabled adults and social

workers to work better together (2016).

This includes the following

commitments:

> We will start with the disabled person’s

own views of their situation, priorities,

aspirations and preferences.

> We will be honest about what is possible

and what is not.

> We will have conversations rather than

being bound by forms and procedures.

> The conversations will be meaningful and

will be about what disabled adults want.

> We will act like people and not just follow

mechanistic processes.

> We will be ambitious for each other,

thinking big and creatively.

> We will show respect for each other’s

choices, preferences and cultures.

> We will listen to and act on what is not

working.

> We will continue to work to overcome

power imbalances between disabled

adults and social workers, leading to equal

relationships and co-producing solutions.

> We will be prepared to talk about how the

context is impacting on us.

> We will talk about money.

> We will look at all options to promote

wellbeing, not just formal care services.

> We will strive to ensure that advocacy is

available for people who need it.

> We will highlight the barriers that prevent

disabled adults from living full lives,

including barriers to work.

Reflective points

> How do the top tips and the

charter reflect your practice

with carers and adults?

> What examples do you have

of good practice and where

might you want to develop

your practice?

Context of assessment

in adult social care

18

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

18

Legal literacy: Assessment for care and support

Legal literacy can be defined as ‘the ability to connect relevant legal rules with the

professional priorities and objectives of ethical practice’ (Braye & Preston-Shoot,

2016, p. 4). It is a mixture of:

Law - doing things right

Assessors need to ensure that their assessments

are lawful and know when to seek legal

guidance. There have been judicial reviews and

Ombudsman complaints about the application

of the Care Act, relating to how well the Care

Act framework, regulations and guidance have

been applied. Assessors and those who support

them can learn from these, for example through

reading case law summaries.

Rights - thinking derived from human

rights and equality

It is important not just to know the letter of

the Care Act 2014, but also to understand the

underpinning human rights law that guides the

principles by which the Care Act 2014 is used –

i.e. the Equality Act 2010 and the Human Rights

Act 1998.

Ethics - doing the right things

Ethical literacy is needed to understand the

spirit of the law, and structural literacy is needed

to understand how the law can be used either

to challenge inequality or to further it (Braye &

Preston-Shoot, 2021, p. 19).

The Care Act 2014’s aim was to simplify, clarify,

update and improve adult social care through a

single law that reflects good practice for adults

and carers. Regulations go alongside the Act

to clarify and explain it further. These include

national eligibility criteria.

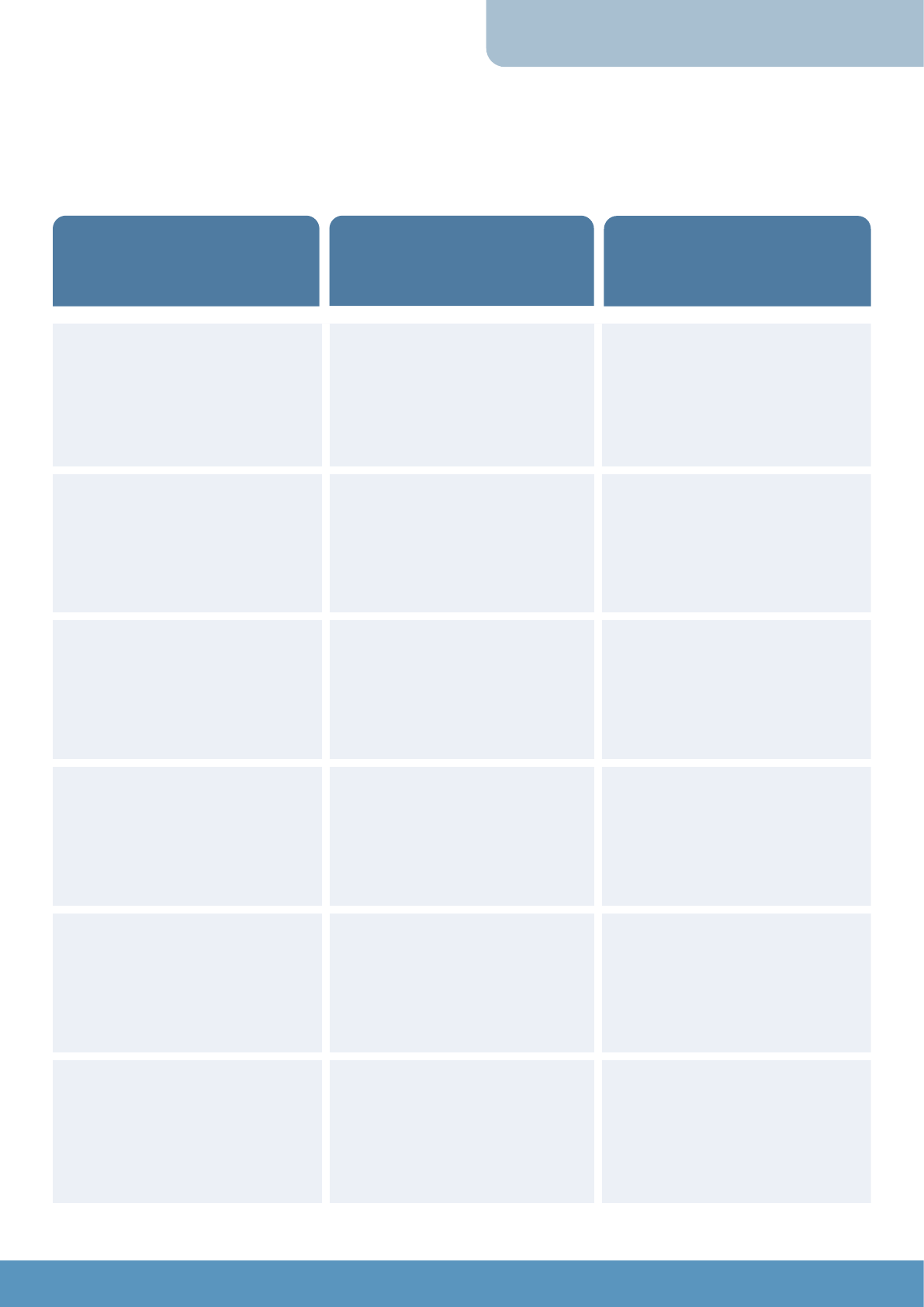

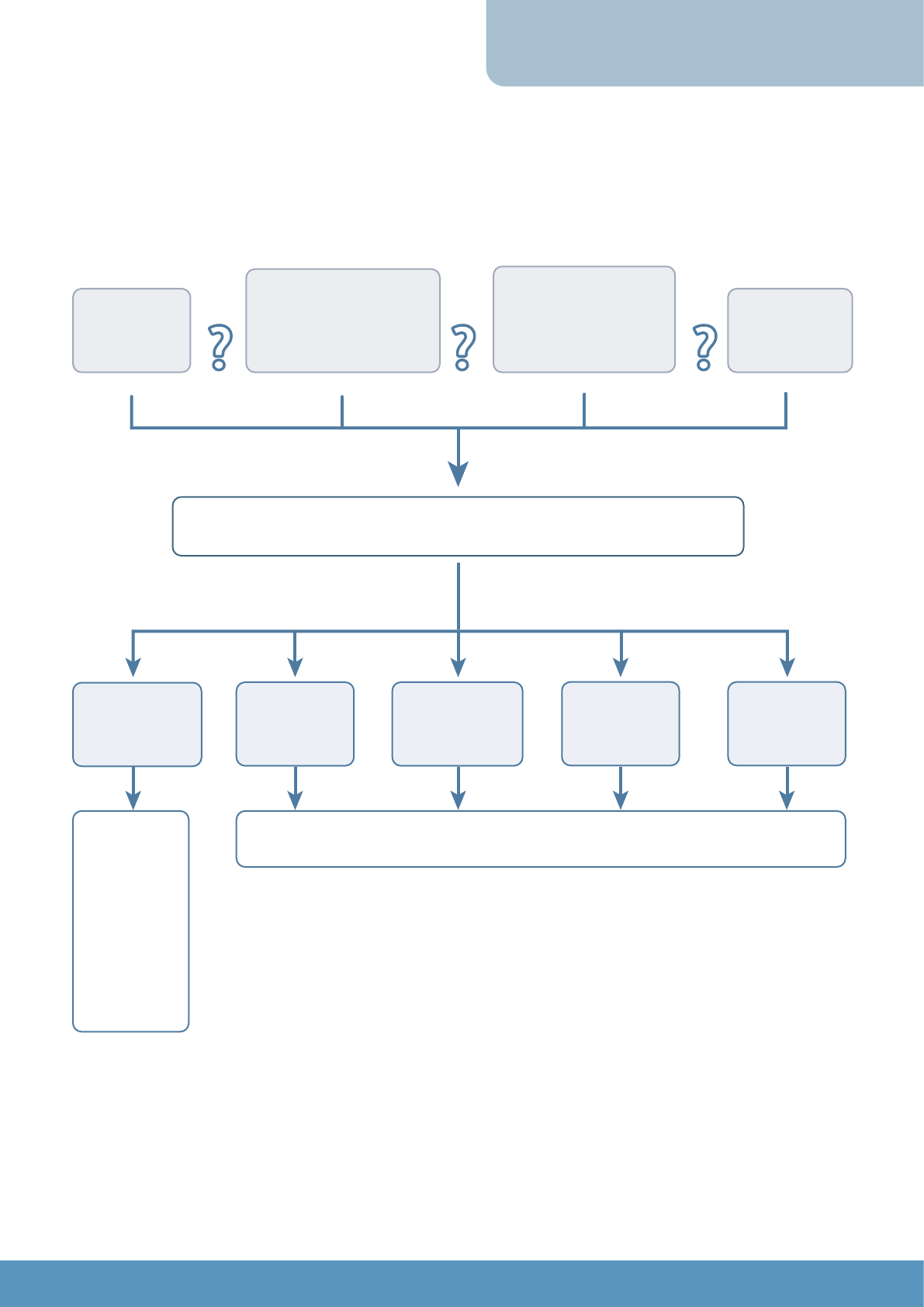

Assessment is part of wider Care Act 2014 duties

(see diagram below taken from the Care and

Support Statutory Guidance, DHSC, 2021a, para.

6.12).

Context of assessment

in adult social care

19

©Research in Practice September 2022

19

18

Throughout the process:

Does the

person have

capacity?

Do they need support

for involvement,

including independent

advocacy?

What is the impact

on the whole family?

Should there be a

carer’s assessment?

Is there a

safeguarding

concern?

If, after review, the care support plan changes - or if the person’s needs or

circumstances change - then a proportionate assessment takes place.

First contact:

assessment

begins

Assessment

process

Eligibility

determination

Care and

support

planning

Review

Needs can

be met by

supporting the

person’s own

strengths,

by universal,

community

or voluntary

services, by

information

and advice, or

by a carer

After assessment, the person and anybody else must be given a record of the assessment.

The person must also receive a written record of the eligibility determination.

Context of assessment

in adult social care

20

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

20

The Care Act 2014 states that the general duty of

a local authority in everything that it does in

relation to identifying and meeting care and

support needs, including assessment, is to

promote that individual’s wellbeing (Part 1,

Section 1(1)).

Does the

person

have

Do they need

support for

involvement,

what is the impact

on the whole

family? Should

there be a carer’s

Is there a

If, after review, the care support plan changes - or if the person’s

needs or circumstances change then a proportionate assessment

First

contact:

Eligibility

Care and

support

planning

Review

Needs can

be met by

supporting

the person’s

own

strengths,

by universal,

community

or voluntary

services, by

information

and advice, or

After assessment, the person and anybody else must be given a record of the

assessment.

These are the areas that need to be considered

in an assessment. There is no hierarchy and all

should be considered for a holistic assessment.

Adults and carers must be assessed where it

appears that they may have needs (including

if those needs are future needs for a carer),

regardless of the level of needs or their financial

resources. Carers may be assessed even if they

are providing care as paid or voluntary work

(DHSC, 2021a, para. 6.17).

Assessment involves looking at an adult’s

needs for care and support, or a carer’s needs

for support, the impact of these on their areas

of wellbeing, outcomes they want to achieve,

and what will help them to achieve that (Care

Act 2014, Part 1, Sections 9 and 10). This should

include consideration of the duties of:

> Preventing, reducing or delaying needs

(Part 1, Section 2).

> Promoting integration of care and support

(Part 1, Section 3).

> Providing information and advice (Part 1,

Section 4).

The duty on the local authority (required by

s9(4)(a) and s10(5)(c) of the Care Act 2014) is

to make judgments concerning the impact of

an individual’s assessed needs on each of the

possible elements of their wellbeing, which are

set out in s1(2). The Care and Support Statutory

Guidance sets out how wellbeing is to be

applied, both for adults and carers. For carers,

this includes the sustainability of the caring role.

The assessment forms the basis of the eligibility

determination.

Wellbeing relates to:

a. personal dignity (including

treatment of the individual with

respect).

b. physical and mental health and

emotional wellbeing.

c. protection from abuse and neglect.

d. control by the individual over day-

to-day life (including over care and

support, or support, provided to the

individual and the way in which it is

provided).

e. participation in work, education,

training or recreation.

f. social and economic wellbeing.

g. domestic, family and personal

relationships.

h. suitability of living accommodation.

i. the individual’s contribution to

society. (Part 1, Section 1(2), Care

Act 2014).

Context of assessment

in adult social care

21

©Research in Practice September 2022

21

20

The Care Act 2014 emphasises the importance

of the adult or carer choosing who should be

involved (Part 1, section 9 and section 10). There

is a duty to provide independent advocacy

where this is needed (Part 1, section 67). This

could include relatives, friends, neighbours,

representatives from other agencies or anyone

who is important to that person.

A local authority may carry out a needs

assessment or carer’s assessment with another

agency (Part 1, section 12). Local authorities

may also assess young people, young carers and

carers of young people who are approaching

18 years of age (Part 1, sections 58-66). The

statutory guidance (DHSC, 2021a) emphasises

that the advocacy duty also applies to children

who are approaching the transition to adult care

and support, when a child’s needs assessment

is carried out, and when a young carer’s

assessment is undertaken.

People have the right to refuse an assessment

(Part 1, section 11). However, assessment should

still be done if the person lacks capacity, or they

are experiencing or at risk of abuse or neglect.

Following the assessment, there is an eligibility

determination (Part 1, section 13), and duties

and powers to meet needs (Part 1, sections 18–

20). The local authority has a duty to ensure that

eligible needs are met, subject to considerations

in relation to residency and immigration status,

needs that are already being met, and choice.

There are national eligibility criteria that give

the threshold for eligible needs. These are based

on meeting three conditions:

> Having needs (because of a physical or

mental impairment or illness).

> Not being able to achieve outcomes in

areas that are specified in section 3 (1) of

the Care Act 2014 (including because the

person needs assistance or it causes pain,

harm or impacts on other areas of well-

being to do so).

> There being a significant impact on their

wellbeing.

The outcomes for adults include personal care,

relationships, occupation and access to services.

The decision on eligibility is made without

reference to what the carer is willing and able

to do, though care and support planning will

include consideration of what the carer is doing.

For carers, eligibility focuses on not being able

to achieve specified outcomes and / or the

consequences or impact of providing care for an

adult, that result in a deterioration of the carer’s

‘physical or mental condition’.

The assessor therefore needs to work with the

individual to understand how needs may be

stopping them achieving outcomes and if there

is significant impact as a result.

Once eligibility has been determined, it is

necessary to identify how eligible needs could

be met. This depends on, firstly, the person’s

ordinary residence and immigration status as

these may be reasons why the local authority

may not meet needs. Secondly, there is a

determination about whether the person wants

the local authority to meet their needs, whether

any needs are already being met, and whether

any services that may be provided are ones

that the local authority charges for. The local

authority can also decide whether it wishes to

use its power to meet any non-eligible needs

(Feldon, 2017).

People whose needs are going to be met by the

local authority will then move onto the next

stage of care and support planning, including

finalising a financial assessment for any financial

contribution from the adult or carer. Care and

support planning includes setting out the

personal budget – the amount of money that the

local authority determines is required to meet

needs. People must be told during the planning

process what needs could be met by a direct

payment, and if the individual requests a direct

payment, they are entitled to receive this if the

criteria are met (Feldon, 2017).

Context of assessment

in adult social care

22

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

22

The requirements in the Care

Act 2014 are for people to be

given:

> A written record of the

determination on eligibility and the

reasons for it.

> (If not eligible) written advice and

information about—

a. What can be done to meet or

reduce the needs;

b. What can be done to prevent

or delay the development of

needs for care and support, or

the development of needs for

support, in the future.

> (If not meeting needs) written

reasons for not meeting the needs

> (If meeting needs) a care and

support plan (adult) or a support

plan (carer), and advice and

information to meet or reduce needs

that are not deemed eligible

> (If meeting needs) a Personal Budget

statement

> (If circumstances change) a revised

care and support plan (adult) or a

support plan (carer).

> The eligibility framework to

ensure that there is clarity and

consistency around local authority

determinations on eligibility.

Main message

Assessors need to be legally literate

and learn from inquiries into whether

the legal rules have not been applied

correctly, for example, through

Research in Practice’s Case Law and

Legal Summaries.

Reflective point

In practice, an assessment often does

not neatly follow legal steps. However,

it must not be led by what is available,

what someone is likely to need or how

much money they have. How do you

ensure that your assessments meet the

requirements of law?

Good practice suggestion

It is important to be familiar with

both the Care Act 2014 letter of the

law and the Statutory Guidance.

Teams or groups of practitioners can

take it in turns to present sections

so that they are reminded of what is

covered.

Signposting

Feldon (2017). The social worker’s

guide to the Care Act 2014. Critical

Publishing

Research in Practice Legal Literacy:

Change Project

Case Law and Legal Summaries for

social care practice

(researchinpractice.org.uk)

Context of assessment

in adult social care

23

©Research in Practice September 2022

23

22

During an assessment, it may be

suspected that someone is at risk of

or is experiencing abuse or neglect. A

safeguarding alert would be made and

the local authority would decide how best

to carry out the safeguarding enquiry

alongside the assessment.

Alternatively, when a safeguarding alert is

made, the enquiry may reveal that an adult

or carer requires an assessment of needs

for care and support. Again, there would

be a decision about how best to carry out

the assessment and the enquiry which are

both required.

Legal literacy: Links to other assessments

The Care Act 2014 states that the local authority must carry out an enquiry if they have

reasonable cause to suspect that an adult is at risk of or is experiencing abuse or neglect

(Part 1, section 42). A safeguarding enquiry may run in parallel to an assessment for care

and support, or for support for carers (DHSC, 2021a, para. 6.57).

The statutory guidance for the Care Act 2014

(DHSC, 2021a, para. 6.11) says that if someone is

unable to request an assessment or struggles

to express their needs, the local authority must

carry out supported decision-making, helping

the person to be as involved as possible in the

assessment, and must carry out a capacity

assessment. The requirements of the Mental

Capacity Act 2005 and access to an Independent

Mental Capacity Advocate apply for all those

who may lack capacity.

Research in Practice partners (2021) identified

the need to be explicit about how the Mental

Capacity Act 2005 principles were considered

in assessment, and to ensure any relevant

information about capacity is recorded.

The Care Act 2014 requires the local authority

to take the individual’s wishes and beliefs very

seriously. The principles in the Mental Capacity

Act 2005 must be considered.

> A person must be assumed to have

capacity unless it is established that they

lack capacity.

> A person is not to be treated as unable

to make a decision unless all practicable

steps to help them to do so have been

taken without success.

> A person is not to be treated as unable to

make a decision merely because they make

an unwise decision.

> An act done, or decision made, under this

Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks

capacity must be done, or made, in their

best interests.

> Before the act is done, or the decision is

made, regard must be had to whether

the purpose for which it is needed can be

as effectively achieved in a way that is

less restrictive of the person’s rights and

freedom of action.

The Care Act 2014 says that a local authority

may only act to promote the individual’s well-

being. The Act does not allow the authority

to make an unwise decision on the grounds

that the individual wishes them to. The Mental

Capacity Act 2005 comes into play if a person is

unable to consent to something. In that case,

the authority may only go ahead with it if it

is in the person’s best interests (Jenkinson &

Chamberlain, 2019).

Context of assessment

in adult social care

24

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

24

Main message

Assessors need to be familiar with the

safeguarding provisions in the Care Act

2014 and also with the Mental Capacity

Act 2005 principles, and know what to

do if someone may not have capacity

to make a particular decision.

Good practice suggestion

Invite a practitioner with experience of

carrying out assessments related to

the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to talk

through the law and practice related

to this.

Signposting

Guthrie (2018). Risks, rights, values and

ethics: Frontline Briefing. Research in

Practice for Adults.

Context of assessment

in adult social care

25

©Research in Practice September 2022

25

24

Adults’ and carers’ experiences of assessment

Responses to the Law Commission consultation (2011) that led to the Care Act 2014

identified that assessments needed to:

> Focus on needs and outcomes.

> Focus on abilities, aspirations and

preferences.

> Involve users, including through advocacy.

> Be appropriate, proportionate and ongoing.

> Be joined up.

> Look at the whole family.

> Be jointly produced by the person being

assessed and the assessor.

> Be transparent.

> Have clear timeframes.

Assessment plays an important part in giving

people control and helping them to identify

and achieve outcomes (Henwood, 2012), as part

of the Care Act 2014’s emphasis on promoting

wellbeing.

The Making It Real statements (TLAP,

2018) are statements developed by people

who use social care about how they want

it to work. These statements are very

relevant to assessment, particularly:

‘I have access to easy-to-understand

information about care and support which

is consistent, accurate, accessible and up

to date.’

‘I can speak to people who know

something about care and support and

can make things happen.’

‘I have access to a range of support that

helps me to live the life I want and remain

a contributing member of my community.’

‘I am in control of planning my care and

support.’

‘I can plan ahead and keep control in a

crisis.’

‘I feel safe, I can live the life I want and I

am supported to manage any risks.’

(TLAP, 2018, pp. 6-8 & p. 10).

Research on implementing the Care Act 2014

(Manthorpe, 2021) gives a mixed picture of

how successful it has been. This is due to the

context of austerity, the complexity of the

social care system, vagueness of terms such as

prevention, and the capabilities and capacity of

the workforce. Research in local authority case

study sites found associations between the

introduction of strengths-based approaches and

reductions in the use of more expensive forms of

long-term care, such as residential and nursing

care, and between community capacity building

and overall reductions in social care spending

and spending on unplanned healthcare (Tew et

al., 2019).

Too many people still receive fragmented and

inadequate assessments, face unmet needs

or experience service-led responses, or do not

have the lawful response needed to ensure their

involvement (Braye & Preston-Shoot, 2021, p. 8).

The specific evaluation on carers’ assessments

highlighted that the number undertaken has

fallen; it also found evidence of infrequent

assessments and reviews, and of shortfalls in the

availability of replacement care, which negatively

impacted on carers’ wellbeing and employment

outcomes (Fernandez et al., 2020, p. 31).

Context of assessment

in adult social care

26

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

26

In September 2016, Think Local Act Personal

(2017) surveyed around 1,100 adults and carers

about their experiences of Care Act 2014

assessment and associated activities. Again,

survey results (60% of respondents were carers)

show progress is still needed:

> Asked what one thing they would most

like to change, 10% of respondents

wanted to see more easily accessible/

good-quality information and advice;

and 21% wanted ‘better quality, more

flexibility or less complexity in arranging

support’ (TLAP, 2017, p. 3).

> Around one in three (34.6%) respondents

said the council ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ listened

to them; an additional one in three

(35.7%) said the council listened to them

‘sometimes’ (p. 9).

> More than half (54.2%) were ‘always’

or ‘frequently’ involved as much as

they wanted in arranging their care or

support; one in four (24.9%) were involved

‘sometimes’ (p. 10).

> Just over two-thirds (68%) were not

offered the support of an advocate (p. 2).

People also identified issues with lack of

assessment or follow-up with support after

assessment, obstacles to getting support,

high thresholds to qualify for support (p. 33),

frustration that carers’ entitlements through

assessment are either not clearly understood

or advertised by councils (p. 37), and having to

tell the same story to different professionals

numerous times (p. 39). Asked to identify one

thing that they would most like to change about

their care and support, the issue most often

identified by respondents (40%) was ‘to make it

more straightforward to understand options’ and

to get and change care and support (p. 32).

There are many disparities in access to

assessment related to information, knowledge,

technology, systems, language, culture,

suitability and stigma. People from particular

groups can face significant barriers, for example,

people who are homeless or autistic adults

(Nosowska, 2020, p. 10). Assessment, when it

recognises and overcomes these disparities and

barriers in access, is an opportunity to promote

equity in access to and distribution of resources.

Systems and processes are important in

enabling positive assessment practice - there is

a section exploring this further towards the end

of the resource.

Main message

Good assessment practice is based

on what people who use social care

say about how they want it to work.

Reflective point

How do you ensure that assessment

is transparent and makes sense to

people?

Good practice suggestion

In a team meeting or practice

forum look at the Making it Real

statements, and consider how far

your practice reflects them and what

else you could do.

Context of assessment

in adult social care

27

©Research in Practice September 2022

27

26

4. Good assessment: Principles of assessment

The Care Act 2014 sets out some principles that underpin work with individuals:

> Beginning with the person’s views,

wishes, feelings and beliefs.

> Thinking about prevention.

> Not making assumptions.

> Ensuring participation.

> Balancing adult and carer needs.

> Protection from abuse and neglect.

> Minimising restrictions.

(Part 1, Section 1 (3))

Involvement: The assessment should start

with the individual’s point of view. Ultimately, it

should be a jointly produced understanding of

the person’s situation. This reflects the exchange

model of social care, where the assessor and adult

or carer exchange expertise about the situation,

rather than the assessor acting as expert (Smale

et al., 1993). The Care Act 2014 emphasises

appropriate and proportionate assessment: this

means that assessment can be done differently

(in terms of depth, timescales and approach) for

different people as long as it achieves its purpose.

But even in a light-touch assessment, assessors

need to keep an open mind about what else

might be going on.

Prevention: The assessment should always

involve asking the question: what can be done

to prevent, reduce or delay needs? Acting

preventatively may involve providing information

and advice, signposting to other services

(e.g. low-level or reablement services), or joint

work with other agencies. It should involve

consideration of the person’s own strengths and

their informal network, as well as the community’s

capacity to support people.

Person-centred: The assessment should

be tailored to the individual and not involve

assumptions. The Equality Act 2010 specifies that

any public sector service must consider how to

‘advance equality of opportunity’ to people with

protected characteristics of: age, race, disability,

gender re-assignment, religion or belief, sex,

sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity,

marriage and civil partnership.

Participation: If the person has difficulty in

giving their point of view, then an advocate should

be considered. This could be an informal advocate

if there is someone willing and appropriate. Or

an advocate may need to be provided. If there is

doubt about capacity, after all reasonable efforts

have been made to support the adult in making

a specific decision, then a mental capacity

assessment must be done.

Balance: The whole family should be involved

and particular consideration given to young

people. It is important that both the adult and

the carer have the opportunity and space to

state their needs. This may require separate

assessments or separate assessors. If needs

conflict, then the assessor may need to act as a

negotiator; again it may be necessary to have two

assessors or to use advocates (Webber & Wright,

2014).

Protection: Assessors need to recognise early

signs of or indicators of possible abuse or neglect.

The discussion about wellbeing should include

how people balance what is important to them

(e.g. relationships) and what is important for

them (e.g. safety). The need for a safeguarding

enquiry may be identified in an assessment.

Any safeguarding activity should start from the

outcomes that someone wants to achieve in their

life.

Reflective point

How far does your assessment practice

reflect the principles above?

Good assessment

28

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

28

Good assessment: Ethics and approaches to

assessment

Assessment is an ethical activity because it involves making judgments about

someone else, and because it has an impact on their life both now and in the

future. There is a close link between social care ethics (see, for example, the British

Association of Social Work’s Code of ethics for social work – BASW, 2021, or the Royal

College of Occupational Therapists Professional standards for occupational therapy

practice, conduct and ethics - RCOT, 2021) and the duty to promote wellbeing that

underpins assessment.

As the Care Act 2014 was embedded, many

local authorities took the opportunity to

change the relationship between the council

and communities. This included aiming to: help

people understand services; build partnerships

with communities; co-produce services; and

re-design conversations to make sure that they

clarify the person’s story and what matters to

them and are asset-focused discussions that

aim to resolve issues (TLAP, 2019, p. 11).

Person-centred approach

An assessor’s view about someone else’s life

cannot be an exact reflection of what it is

really like for them: rather, it is a constructed

account of who they are and what is happening

for them. This raises the question of whether

our record says more about our perspective

than it does about the adult or carer. It also

requires us to question how the idea of someone

is constructed – for example, what makes

someone ‘at risk’ and how does this affect how

they are perceived? (Guthrie, 2018, p. 3).

It is essential that the assessment we do is

jointly produced with the person that it is about

so that they recognise their own self in it. Also so

that we do not impose our values and views on

them.

Working in a person-centred

way is based on the following

values:

> People have the right to choose

how to live their life and are able to

do this with adequate support.

> Power should be shared so that

solutions are jointly produced.

> People are experts in their own lives.

> Planning should start with the

positive aspects of someone’s

life – the things they can do, their

passions and interests.

> People have assets, strengths and

capacities that they can bring to

bear on their situation.

> Communities can be built which

are inclusive and recognise the

contribution of all people.

> Everyone can build meaningful

connections.

(Sanderson & Lewis, 2012)

Context of assessment

in adult social care

29

©Research in Practice September 2022

29

28

Good assessment

Relationship-based practice

Relational work counters the tendency to be

procedural and for the assessment conversation

to be led by the assessor. In a relational

assessment, the conversation is reciprocal and

is built around getting to know the person and

what is important to them. There are some core

characteristics of this approach:

> Each inter-personal encounter is unique.

> Human behaviour is complex and multi-

faceted.

> The internal and external worlds of

individuals are inseparable, and so the

relationship needs to take into account

both the individual and their context.

> Relationship is the means through

which interventions are channelled.

(Ruch et al., 2018)

Strengths-based practice

A strengths-based approach involves

collaboratively exploring the person’s

circumstances and experiences with a focus on

their abilities and on the enablers and barriers

to them thriving. Research in Practice partners

(2021) point out that there has been a shift in

assessment practice from talking about deficits

to identifying what people can do. This is not

about ignoring needs but about putting them

in context and balancing them with strengths.

It is important to tell the person’s story and to

be able to identify them as an individual. This

reflects the statutory guidance, which highlights

the importance of encouraging people to use

their gifts and strengths (DHSC, 2021a, para.

6.63).

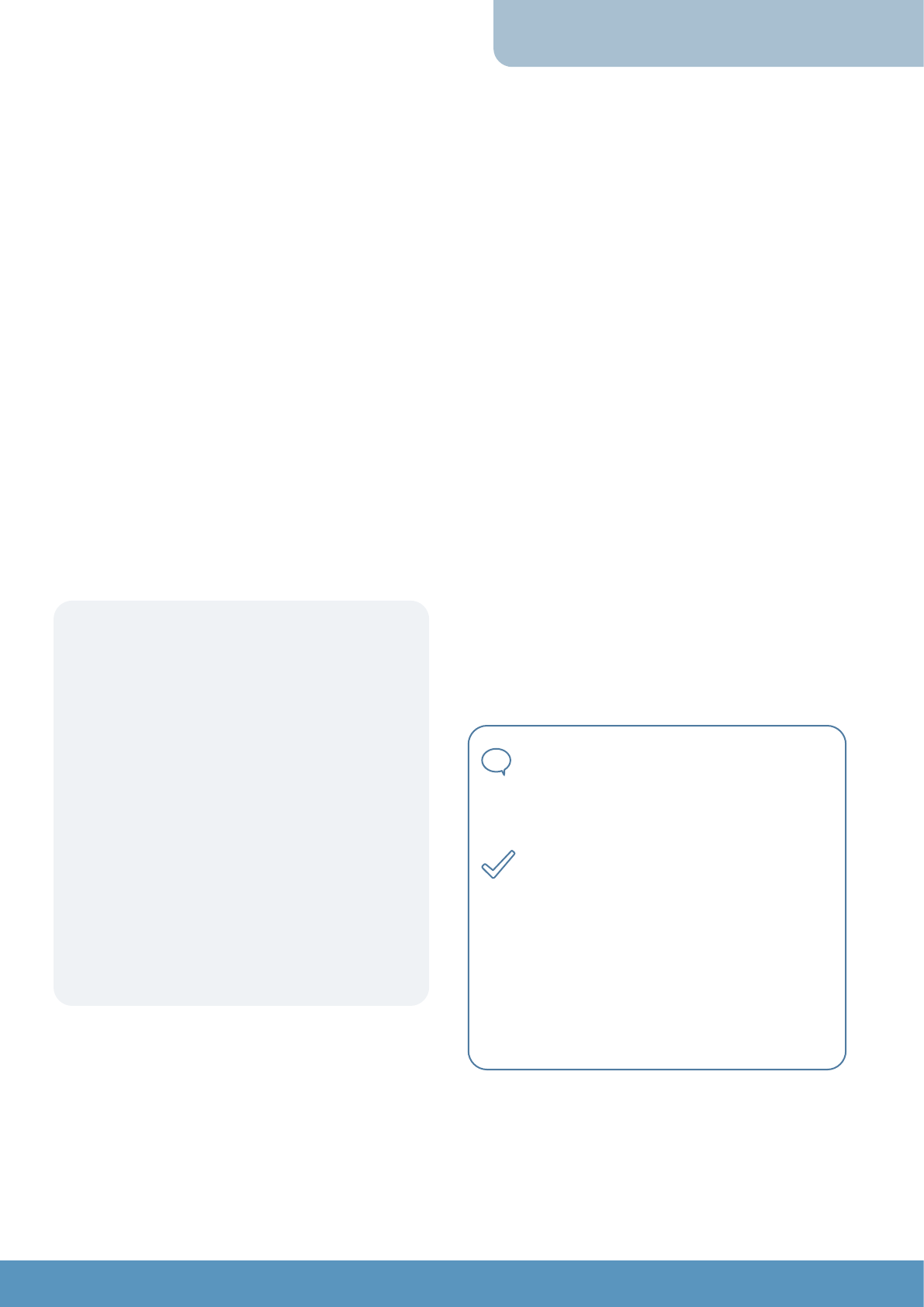

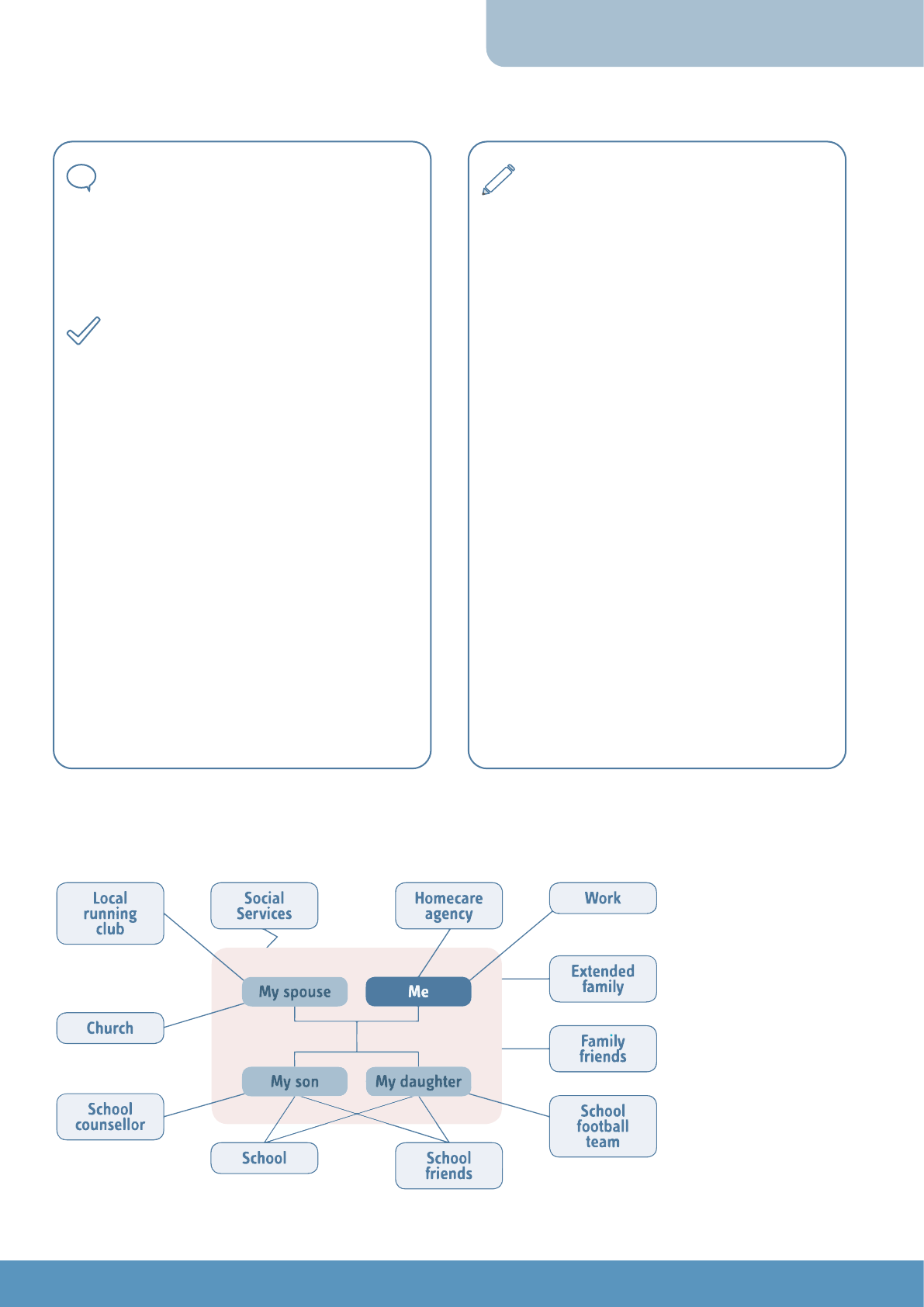

The strengths-based approach to

assessment is about having a dialogue to

identify the person’s own strengths, wishes

and priorities at various levels, the strengths

of the person’s supporting network such as

their family or friends and neighbours, and

their wider network of support, for example

local groups, voluntary organisations or local,

outlets (see diagram below DHSC, 2019, p.

45).

What have you previously enjoyed doing?

What level of independence did you once have?

What level of independence would you like to have?

What can you manage to do now?

What would like to be able to manage?

Who can support you?

Let’s plan how

you can achieve

what you wish

to and live a

fulfilling life.

Exploring these themes during the assessment conversations should help to

identify realistic expectations and the person’s desired outcomes

> The assessment is not the

document or the form.

> The assessment is a holistic

intervention.

> ‘The process of gathering

information’ can consist

of various visits, several

conversations, reading

documents, etc.

Signposting

Research in Practice (2020).

Strengths-based practice (film)

Guthrie and Blood (2019). Embedding

strengths-based practice: Frontline

Briefing. Research in Practice.

30

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

30

Human rights approach

Assessment is an activity where professional

judgment is applied in the situations of people

whose independence and autonomy might be at

risk. Therefore, its aims must align with human

rights values (BIHR, 2016).

The essential elements of the assessment

duty set out in the Care Act 2014 and

their relation to Articles of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights

1

are:

> Adults and carers must be assessed

where it appears that they may have

needs, regardless of the level of needs

or their financial resources (Part 1,

section 9(1-3)). This relates to Article

14 – freedom from discrimination.

> Assessment involves looking at the

adult’s or carer’s needs, the impact

of these on areas on wellbeing,

outcomes they want to achieve and

what will help them to achieve that

(Part 1, section 9(4)). This relates

particularly to Articles 2, 5, and 8 –

right to life, freedom from degrading

treatment, and respect for private and

family life.

> The adult and carer must be involved,

along with any person whom the

adult asks the authority to involve or,

where the adult lacks capacity, any

person who appears to the authority

to be interested in the adult’s welfare

(Part 1, section 9(5)). This principle of

involvement echoes Article I – that ‘All

human beings are born free and equal

in dignity and rights’.

1 www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-hu-

man-rights

A human rights approach to assessment

includes actions to: get to know the person, their

preferences and choices; understand how the

person is able to exercise their rights; identify

barriers and enablers to the person’s dignity and

rights being upheld; and make judgments about

how best to empower the person to live a life of

dignity and equality (Nosowska, 2020, p. 11).

Signposting

Nosowska (2020). Embedding human

rights in assessment for care and support:

Frontline briefing. Research in Practice

Good assessment

31

©Research in Practice September 2022

31

30

Good assessment

Anti-oppressive practice

This approach calls for practitioners to be aware

of the impact of oppression on individuals and

of its presence in their lives. Assessors can add

to people’s experience of oppression – either

deliberately or unconsciously – by reinforcing

stereotypes, making assumptions or accepting the

structural problems that people face as inevitable.

An anti-oppressive assessment takes into account

the personal, cultural and structural barriers

that someone faces, including the potential

for the assessment to reinforce or reflect these

(Thompson, 2016). This can be explored through

using an intersectional lens, which is discussed

later in the section on building a relationship (see

page 32).

Ethics of care

Ethics of care is a theory of moral behaviour.

It is about how we respond to each person

with empathy and compassion. There are

four main elements that make up an ethical

response (Tronto, 2005):

> Attentiveness:

recognition of the other person’s needs

> Responsibility:

taking it upon ourselves to care

> Competence:

having the capability to act

> Responsiveness:

understanding how the other person is

receiving the care.

These elements link to the standards of

conduct, performance and ethics for registered

professionals. These emphasise the importance

of acting in the best interests of people and of

being ready and capable to do so.

Confidentiality and consent

Assessment requires the same ethical standards

as any form of enquiry into someone’s life – it

should be done with consent, and the information

gathered should remain confidential apart from

where information sharing is agreed. People should

be able to withdraw their consent to take part

or for information to be used. Advocacy may be

required, and the Mental Capacity Act 2005 should

be followed.

The data protection principles in the Data

Protection Act 2018 are helpful. Personal data

should be:

> Used lawfully for a specific purpose.

> Adequate, relevant and not excessive.

> Accurate and up to date.

> Shared for a purpose and with consent except

in certain exceptional circumstances

> Kept safely and only for as long as needed.

This applies to all methods of assessment, so in a

virtual environment it is important to check privacy

and security of the conversation.

Main message

Assessment has an impact on people’s

lives and is, therefore, an ethical activity.

Good practice suggestion

In a team meeting or practice forum,

read through an assessment and

discuss how this would impact on

the person who was being assessed.

What ethical dilemmas are there in the

situation? Which values underpinned

the way in which the person was

assessed?

32

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

32

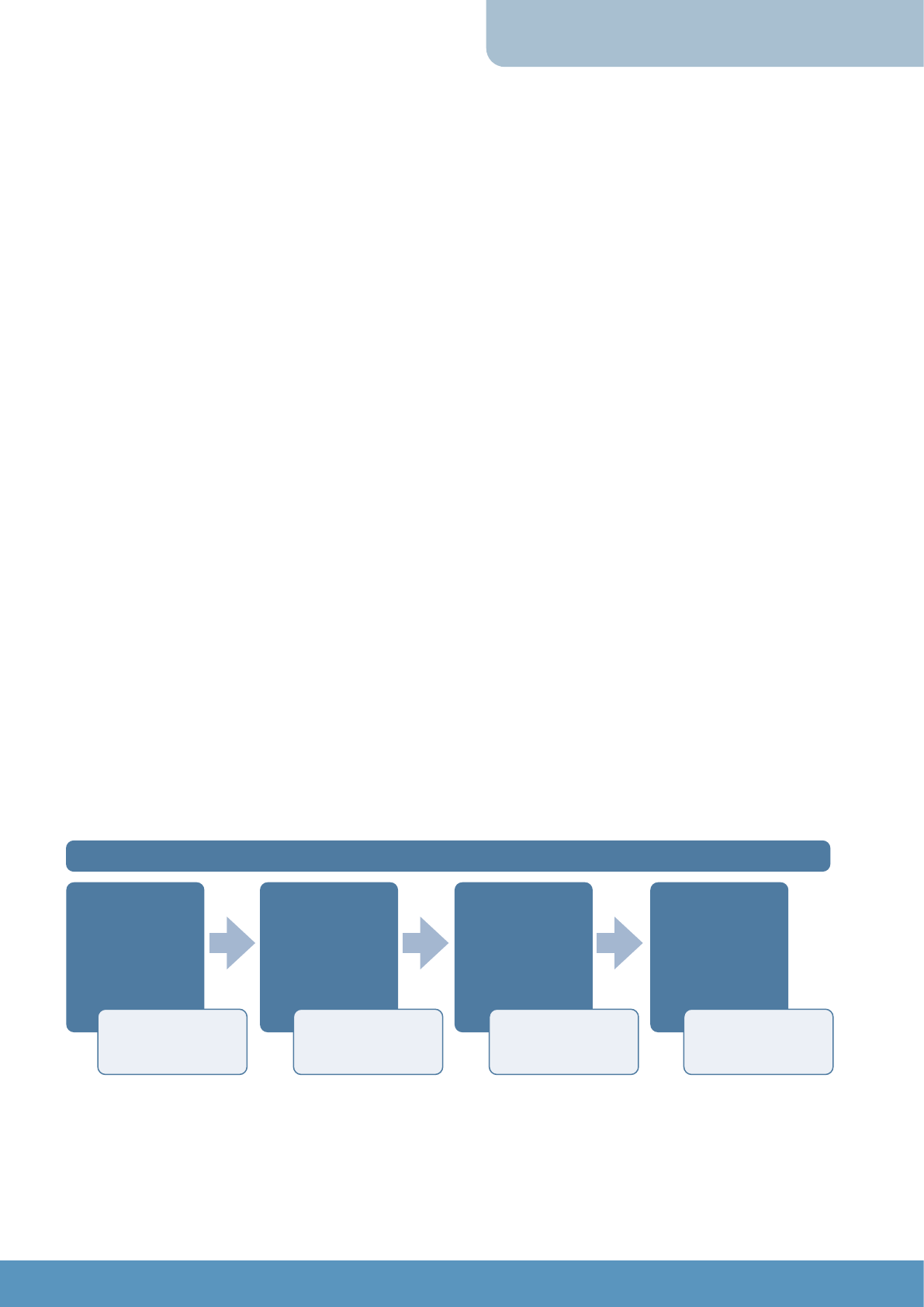

Good assessment: Assessment steps

It is helpful to think of assessment as a series of steps, each of which is important in its own right and

which together lead to the final purpose of promoting wellbeing.

The steps for assessment are:

1. Building a relationship

2. Gathering information

3. Analysing the information

4. Making a judgment.

Main message

Assessment can be considered as a

series of steps with the ultimate goal

of promoting wellbeing.

Good practice suggestion

Look at an assessment record and

see if you can identify the steps of

building a relationship, gathering

information, analysing the information

and making a judgment. How was this

done?

Through building a relationship and gathering

information, we are able to determine what the

story is. Analysis enables us to understand what

the story means. We then make a judgment

which informs our eligibility determination and

any care and support planning that is required.

Research in Practice identified five Anchor

Principles for carrying out good analytical

assessments and interventions in Children’s

Services. These are questions that help

practitioners to work through an assessment,

intervention and review in a clear way. The

questions are:

> What is the assessment for?

- referral

> What’s the story?

– assessment

> What does the story mean?

– assessment

> What needs to happen?

– care and support planning

> How will we know we are making progress?

– review.

(Brown et al., 2014)

Good assessment

33

©Research in Practice September 2022

33

32

Good assessment

Miss Higgins lives alone in a bungalow in a small village on the outskirts of Maytown. She moved there

ten years ago when she retired. Miss Higgins has no close family. She had local friends in Maytown but

has lost touch with them in the last few years. However, she has friends that she phones regularly in

other parts of the country.

Miss Higgins’s closest friend in Maytown, Ann McDonald, died two years ago after a series of strokes.

For a few years before that, Miss McDonald had mostly been unable to go out, and Miss Higgins had

been looking after her, visiting her every day. Molly and Ann had been friends for 30 years and used to

travel together frequently.

Miss Higgins was a piano teacher and still has a piano at home, though she rarely plays now because

she has arthritis. She taught many of the children in the local area over the 40 years before her

retirement. She loves listening to music and used to attend a lot of concerts. Miss Higgins is also

interested in films and film scores.

Miss Higgins was admitted to hospital two months ago with breathing difficulties. She had severe

pneumonia and was in intensive care. When she came into hospital, Miss Higgins had clearly not

eaten for some time and was very dehydrated. She also had pressure sores. Miss Higgins has gradually

recovered and had rehabilitation to be able to walk with a Zimmer frame. Miss Higgins still becomes

tired very quickly and has difficulties gripping objects. She also gets a lot of pain in her legs from the

arthritis and from pressure sores that restrict how well she can move around.

During her time in hospital, Miss Higgins has been refusing all visits to her home and any discussions

about support, including referral to the hospital discharge team. It gradually became clear that

nobody has been to her home for the last four years, or perhaps longer.

Miss Higgins says that she just wants to go home and be left alone.

Miss Higgins has no close family, having moved to the area from North Wales many years ago.

One of the nurses on the ward, who was taught by Miss Higgins, believes that she and Miss McDonald

were in a relationship.

Miss Higgins is also interested in films and film scores, and in songs in her first language, Welsh.

Case study: Molly Higgins

This case study will be referred to as we look at the steps to carrying out a good assessment.

It is based on a real assessment provided by the original Change Project Development Group

and updated for the second edition. It is based on a real situation provided by the original

Change Project Development Group, though not a real person, and was updated for the

second edition.

Reflective point

Before starting an assessment, it is useful to reflect on the purpose of the assessment. This

helps to start the process of building a relationship and gathering information by identifying

some of the relevant issues to focus on. In this case, what do you think the assessment is for?

34

Good Assessment Practitioners’ Handbook Second edition

34

Step 1: Building a relationship

Assessment is a human encounter. A good

relationship is needed to enable positive

outcomes and experience (Ruch et al., 2018). The

experience of relational work may be therapeutic

– for example, it may reduce the person’s

experience of loneliness (DHSC, 2020).

Building a relationship involves using yourself to

gain trust, to establish rapport and to open up

communication. Use of self includes awareness

of how our beliefs, values, experiences and views

impact on our understanding (reflection) and of

how they affect the situation itself (reflexivity). It

involves acknowledging the emotion that is part

of the assessment contact both for the assessor

and for the person being assessed. It demands

honesty about the impact of assessment.

Taking a relationship-based approach to

assessment allows the assessor to avoid an

understanding of the person’s situation that is

based on probability or procedure (Ruch, 2012).

It is helpful to use information about what is

likely to happen and to use procedures to help

us follow steps that usually work, but this can

lead to an oversimplified view of what is going

on or to a routine response. But if we have a

relationship with the individual, then we are able

to:

> Recognise them as a unique individual.

> See what is unique to their situation.

> Identify the gaps between what we

know from research and from previous

experience, and what is happening here.

The level of relationship that is needed will be

proportionate and appropriate to the situation.

Adults and carers value both the relationship

and practical action (Beresford et al., 2008). If

someone is clear about what they need and their

focus is on getting this, then they may prefer

to focus on practical action rather than the

relationship. In other situations, the person may

have great need for empathy and understanding

before they can start to work out what is

happening and what it means.

Research in Practice Partners (2021) pointed

out that the first encounter can be a powerful

opportunity for intervention and so it is

important to give time to the person. The

practitioner acts as a listener not a judge,and

trust is built through the person experiencing

attention without judgment. This approach

helps to understand risks and strengths through

the person’s eyes and enables them to feel more

in control of their identity (Felton & Stickley,

2018). The amount of time needed to build the

necessary level of relationship will depend on the

individual and their situation, and the skills of the

assessor. It may be possible to build sufficient

relationship through a phone call, or it may be

necessary to have extensive face-to-face time

with someone.

It may be that someone else, for example, a

health practitioner, care worker or voluntary

organisation, already has an established

relationship with the person and can help you to

build your relationship. User-led organisations

and advocates can also support initial contact

and relationship building.

Good assessment

35

©Research in Practice September 2022

35

34

Good assessment

The relationship should be an adult-to-adult relationship that is based on an exchange of expertise