Fitting In: Young British Women’s

Reported Experiences of Body Modification

Abigail Tazzyman

PhD

University of York

Women’s Studies

September 2014

1

Abstract

This thesis investigates female cultures of body modification in contemporary

Britain. I begin from the premise that women in current UK society are concerned

about their appearance and subjected to significant media pressures to engage in

body modification. By body modification I mean the methods which women use in

order to alter their physical body and appearance. All methods (invasive or non-

invasive; self-administered or other-administered; permanent or temporary) are

considered, provided the intention of their use is primarily to alter the user’s physical

appearance. Based on qualitative life-history interviews with thirty university-

educated British women aged between eighteen and twenty-five my research

investigates the choices of, motives for, influences on and relationships of women to

their practices of body modification.

The analysis chapters of this thesis deal with three key stages in my participants’

development during which body modification emerged as important. These are the

point when my participants went to school, their years at university and their entry

into the world of work. The analysis chapters focus on these three stages. The first

one explores participants’ initial engagement with and experience of body

modification during the school years. The second centres on their use of body

modification while at university, and the final analysis chapter explores their

engagement with these practices in the world of work. I also discuss my participants’

expectation of their future engagement with body modification.

Unlike third-wave feminist discourse, which frequently refers to body modification

in terms of freedom and choice, my findings offer a completely different

understanding of women’s engagement in these practices. In the life stages I focus

on, sociality and taking cue from others emerged as the most important aspects of

women’s body modification decisions.

2

Table of Contents

Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 1

Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... 2

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. 5

List of Images ............................................................................................................. 6

Lists of Tables ............................................................................................................. 7

Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 8

Author’s Declaration ............................................................................................... 10

1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 11

Literature Review ................................................................................................... 17

Empirical Research ............................................................................................. 17

Non-Feminist Work on Body Modification........................................................ 24

Feminist Approaches .......................................................................................... 30

Conclusion .............................................................................................................. 54

2. Methodology ......................................................................................................... 56

My Research Perspective ....................................................................................... 56

Research Design ..................................................................................................... 58

Why interviews? ................................................................................................. 58

Research Sample ................................................................................................. 60

Recruiting Participants ........................................................................................ 61

Research Ethics ...................................................................................................... 65

Writing Auto-Ethnographically as a Pilot .............................................................. 67

The Interview Process ............................................................................................ 70

Interview Preparation .......................................................................................... 70

Conducting the Interviews .................................................................................. 72

Interviewer/ Interviewee Relationships .............................................................. 77

Bodies in the Interview Process .......................................................................... 79

Being an Insider/ Outsider: Interviewer Positionality ........................................ 81

Issues Raised During the Interview Process ....................................................... 86

Transcribing and Analysis ...................................................................................... 89

Conclusion .............................................................................................................. 95

3. Learning to Follow: First and Early Experiences of Body Modification ........ 96

3

Peer Influence ......................................................................................................... 98

Embodiment, Objectification and Sociality ......................................................... 104

Stigma ................................................................................................................... 108

Consumption Practice ........................................................................................... 110

Peer Approval ....................................................................................................... 114

Becoming a Woman ............................................................................................. 118

Maternal Influence ............................................................................................... 122

Change .................................................................................................................. 136

Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 142

4. Adapting to New Environments: University and Young Adulthood ............ 146

Rhetorics of Change ............................................................................................. 149

New Environments and Changing Identities ........................................................ 152

Communal Living ................................................................................................. 168

Relationships ........................................................................................................ 173

Classed Appearance ............................................................................................. 175

Weight and Identity .............................................................................................. 178

Dressing Up .......................................................................................................... 185

Internalisation and Self-Regulation ...................................................................... 189

Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 191

5. Changing Expectations: The World of Work and Beyond. ........................... 194

The Professional Image ........................................................................................ 197

Class and Professionalism .................................................................................... 203

Image Differences Between Job Sectors .............................................................. 207

Dressing to Impress and Looking the Part ........................................................... 208

Gender and the Professional Image ...................................................................... 219

Life Trajectory and Body Modification ............................................................... 221

Ageing Bodies ...................................................................................................... 230

Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 241

6. Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 244

Key Debates ......................................................................................................... 244

My Findings and Contributions to Knowledge .................................................... 247

Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 260

Appendix A: Call for Participants ........................................................................ 264

4

Appendix B: Consent Form .................................................................................. 265

Appendix C: Participant Information Sheet ....................................................... 266

Appendix D: Support Contacts and Information for Participants ................... 268

Appendix E: Interview Schedule .......................................................................... 269

Appendix F: Body Modification Methods Categorisation ................................. 271

Appendix G: Participants’ Demographic Details ............................................... 275

Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 279

5

List of Figures

Figure 1. Feedback loop diagram

6

List of Images

Image 1. Screen shot from Pinterest

Image 2. Elle magazine online work wear article ‘Elle’s Working Wardrobe’.

Image 3. Harper’s Bazaar front cover for October 2010.

Image 4. Times Style Magazine work wear article ‘New Work Wear Rules’.

Image 5. Times Style Magazine work wear article ‘Work it Out’.

Image 6. Cosmopolitan online work wear article ‘What to Wear to Work’.

Image 7. Marie Claire online work wear article ‘What to Wear to Work’.

7

Lists of Tables

Table 1. Practices Engaged in by Participants

Table 2. Researchers Relationship to Participants

Table 3. Assumed Relationship of Researcher to Participants After the Interview

Table 4. Analysis Themes

Table 5. Practices Engaged in During the School Years by Participants

Table 6. Practices Engaged in During University by Participants

Table 7. Practices Engaged in by Participants in the Work Environment

Table 8. Participant Employment Status at the Point of Interview, 2012

Table 9. Acceptable and Unacceptable Appearance Adjectives

8

Acknowledgements

Thank you firstly to my participants. Without them and the rich data they provided

me with this research could not have taken place. I am indebted to their generosity in

the time they gave and the histories they shared with me.

I cannot thank enough my wonderful supervisor, Gabriele Griffin, who provided

unwavering support, encouragement and guidance throughout the PhD process. You

helped me both to keep on track and to venture down new roads to develop myself as

an academic. I am incredibly grateful for all the help you have given me.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Stevi Jackson and Ann Kaloski-Naylor,

for the thought-provoking insights and guidance they gave as my Thesis Advisory

Panel members and for the opportunities they and the Centre for Women’s Studies

provided, enabling me to develop as a researcher, teacher and scholar. Also a huge

thank you to Harriet Badger for your help and support in the multitude of projects I

have undertaken while a member of the Centre for Women’s Studies at the

University of York: so many of these could not have taken place without you.

Amy Godoy-Pressland (University of East Anglia): thank you for all your advice and

encouragement as a mentor and the opportunities you have given me to disseminate

my research further afield. Thank you to Prof Ruth Holliday from the University of

Leeds for the ideas and the inspiration you offered for my PhD research and the

future.

To my co-organiser of so many projects and conferences, Bridget Lockyer: you have

been an inspirational friend and colleague and I am grateful to have had the

opportunity to work with you, and hope to continue to do so. My friends and

colleagues at the Centre for Women’s Studies provided me with a supportive and

stimulating environment throughout my PhD and I truly appreciate this.

I am incredibly grateful to my family who have given me constant support over the

last three years. The stories of my Grandma Olive inspired my desire to listen to

women’s voices and her support enabled me to do so. My twin brother Seb asked

9

questions like no one else and put life back into perspective with such humour; I

thank him for always being there. I would also like to thank my partner Ash for

everything, for helping me in whatever way I needed throughout this process, be it

proof reading, listening to yet another conference paper, or simply reassuring me that

I could do it. You gave me the encouragement to always keep striving for the best

and the support to get there.

Finally, thank you to mum and dad. Without the two of you this PhD would not have

been possible. You have continuously supported me, patiently listened, persistently

shown interest in my work and always inspired me. You instilled in me the

importance of questioning the taken-for-granted and in doing so led me to my

research and my feminism.

With thanks to Funds for Women Graduates (FFWG) for funding me through the

final year of this PhD.

10

Author’s Declaration

I certify that all the research and writing presented in this thesis is original and my

own. No part of this thesis has been submitted for another award.

11

1. Introduction

Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes

itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its

prison (Wollstonecraft 1792 [2004]: 47).

What do contemporary young British women say about why they engage in body

modification? Beginning from this research question my thesis focuses on female

cultures of body modification in contemporary Britain. I investigate the choices of,

motives for, influences on and relationships of women to their practices of body

modification and how they articulate these. By body modification I mean the

methods which women use to alter their physical body and appearance. Thirty

women took part in this project, aged between eighteen and twenty-five, whom I

interviewed in 2012. I approach this topic from a life course perspective. Given that

my research participants were relatively young (18-25), when I speak of a life course

perspective I do not mean to suggest that this research covers an interviewee’s entire

life course. Instead, it mainly looks back over the life of my participants up until the

point of the interview and focuses on the life stages which in their interviews

emerged as critical in the development of their body modification regimes: school,

university and the work place. My thesis is organised accordingly.

For this research I was open to discuss all possible methods of body modification

(e.g. invasive or non-invasive; self-administered or other-administered; permanent or

temporary). In reality the practices discussed by my participants were very limited;

no one, for example, had engaged in cosmetic surgery or envisaged doing so in the

near future, and little invasive modification had been undertaken. The most

permanent methods disclosed were tattoos and piercings, though these were limited

in the extent of their use. The practices my participants reported engaging in and

identified as body modification during the interviews are documented in Table 1.

12

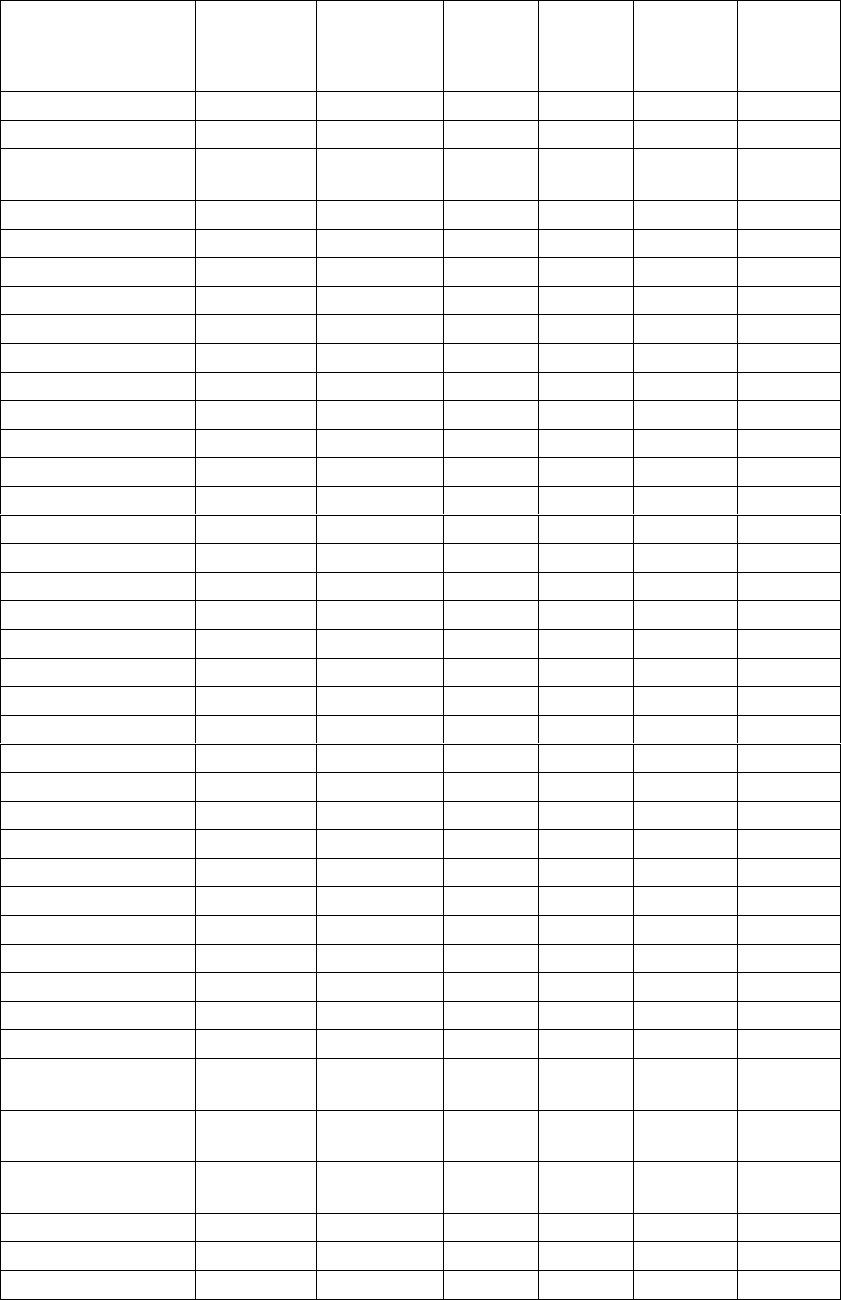

Table 1. Practices Engaged in by Participants

Practices engaged in and identified as body modification by participants in

alphabetical order

Control underwear/ shapewear

Dieting

Dress

Ear piercing

Eating disorder

Exercise

Fake tan

False nails

Hair dying

Hair removal

Hair straightening

Hair styling

Heels

Makeup

Nails (paint/ file/ decorate)

Other piercings

Plucking/waxing eyebrows

Self-harm

Skin regimes (cleanse, tone, moisturise)

Tattoo

Teeth whitening

Tinting eyebrows and lashes

Source: Interview Data.

While the popular media portray methods such as cosmetic surgery and Botox

injections as seemingly commonplace, when one thinks of one’s own practices,

certain parameters exist as to what one is and feels able to engage with. This means

that on the whole, invasive, permanent and ‘extreme’ methods rarely feature, if at all,

in the mundane daily practices of women’s beauty regimes. This was the reality for

my participants and the overwhelming majority of women I encountered throughout

this research. A discrepancy thus exists between certain popular media discourses on

female body modification and women’s lived experiences of these practices, a

discrepancy which this thesis in part seeks to investigate.

Two alternative ways one may think about more extreme forms of body modification

are eating disorders and self-harm. At the time of the interview three of my

participants had or had previously had an eating disorder and two had self-harmed. In

addition to these women, eight of my participants spoke about eating disorders as a

13

form of body modification and one woman included self-harm in the category. Given

the association of eating disorders and self-harm with complex social issues, some

may question whether they can be talked about in the same way as practices such as

hair removal or makeup for example. However I treat them in the same way here

because, in so far as they were mentioned, this is how they were articulated by my

participants.

My participants’ experiences of body modification highlight the significance and

pervasiveness of these practices in the female life course and their importance for

individual identity. The contemporary west is a culture where it is almost impossible

to avoid being a constant witness to images of modified bodies and body

modification methods. Women (and to a lesser degree men) are endlessly assailed by

exhortations to manipulate their bodies to fit in with certain body norms. We are

besieged by cultural imperatives to constantly think about the body and to see it as a

project to work on. A simple Google search makes this clear: typing in ‘Body

Modification’ produces 17,900,000 hits, ‘Female Body Modification’ provides

2,440,000 results, ‘Cosmetic Surgery’ 30,700,000, ‘Weight Loss’ 420,000,000,

‘Cosmetics’ 181,000,000, and ‘Shaving’ 83,400,000.

1

The vast majority of these hits

are for adverts and advice. This emphasis on bodily appearance is overt in the

popular media and highly gendered. TV shows such as Secret Eaters

2

(2014) and

How to Look Good Naked

3

(2008) are dedicated to the topic. Women’s appearance is

inspected and critiqued (Denham 2014; O’Carroll 2014; Rose 2014); women’s

magazines overwhelmingly dedicate their pages to practices of body modification

4

and despite the economic climate, the cosmetic/beauty/fitness industries are growing

(King 2013; The Leisure Database Company 2013; Mintel 2013; Delineo 2014). The

high visibility of issues surrounding body modification is indicative of the

1

Google search undertaken on the 6

th

May 2014.

2

Secret Eaters is a British documentary television series about overeating which scrutinises the eating

habits of families considered overweight by putting them under 24-hour camera surveillance.

Broadcast by Channel 4, May 2012 – 2014, 8pm weekday evening (three series).

3

How to Look Good Naked is a British television show in which fashion stylist Gok Wan encourages

women and men who are insecure about their bodies to strip nude for the camera, and teaches them to

dress ‘better’ for their body shape. Broadcast on Channel Four, June 2006-April 2008, weekday

evenings (four series).

4

Vogue, Elle, Look, Glamour, Instyle, Women’s Health Magazine and Marie Claire for example all

give a large proportion of their pages over to body modification.

14

importance it holds in contemporary western culture and the extent to which its

enactment permeates society.

Body modification then is a highly normative gendered practice which for the most

part goes unquestioned. It acts as the tool of necessity for women’s attempts to reach

a certain feminine ideal propagated in a capitalist patriarchal society. That feminine

ideal is represented by those women in the public eye who are celebrated for their

appearance and attractiveness, such as Beyonce,

5

Scarlett Johansson,

6

Michelle

Keegan

7

and Kate Upton

8

. These women all feature highly in public rating lists of

attractiveness such as FHM’s ‘The Official 100 Sexiest Women in the World 2014’

9

.

They are slim, well-toned, have curvaceous figures, clear skin and shiny hair. When

a woman in the public eye fails to meet this ideal negative reactions are frequent. For

example as I revise my thesis (May 2014), there is a debate in the British media

about the treatment of a young female opera singer who was criticised for being

overweight. The woman in question was subjected to a large volume of negative

criticism for her appearance by opera critics in the press. Phrases such as ‘a chubby

bundle of puppy-fat’ (Clark 2014) and ‘unsightly and unappealing’ (Morrison 2014)

dominated reviews, while little was said of her actual performance (though when

mentioned her singing was highly praised). This sparked off a public debate about

the sexism of these comments, the importance given to female appearance above all

other attributes, in this case an opera singer’s ability to sing, and the body shaming of

women who are in the public eye (Dammann 2014; Lowe 2014; Rayner 2014). This

incident illustrates the importance of women’s looks for how they are judged.

Women in the public eye are constructed as role models and as illustrators of socially

acceptable and unacceptable femininity through the public discussion of their looks.

This informs other women’s (and men’s) understanding of ideals of feminine looks

in contemporary British culture.

5

Beyonce is a highly internationally successful American singer and actor.

6

Scarlett Johansson is an American actor, model, and singer

7

Michelle Keegan is a British actor.

8

Kate Upton is an American model and actor, known for her appearances in the Sports Illustrated

Swimsuit Issue.

9

FHM is a British monthly men's lifestyle magazine. Each of FHM's international editions publishes

yearly rankings of the sexiest women alive based on public and editorial voting through the

magazine's website.

15

The importance of appearance in the contemporary west is a crucial aspect of this

study. In the popular imagination appearance is equated with identity, which has

been acknowledged from a variety of perspectives (Goffman 1963; Lindemann 1997;

Lawler 2008; Jackson and Scott 2010). The association of appearance with identity is

noticeably gendered. It has been repeatedly highlighted that in the contemporary

west the attribute viewed as the most important aspect of a woman is her appearance

(Wolf 1991; Bordo 1993 [2004]; Jeffreys 2005). For men appearance holds less

prominence in terms of cultural perceptions of its value. Instead a wide range of

attributes and abilities contribute to the judgements of men’s worth (Burton,

Netemeyer and Lichtenstein 1995; Davis 2002; Norman 2011). While it has been

acknowledged that men now face more pressure in relation to their appearance,

particularly in masculinity studies, this pressure has been understood as both less and

different from that faced by women (Davis 2002; Wright, O’Flynn and Macdonald

2006; Norman 2011). As appearance is culturally so important for women’s identity

and perceived value, it is important to understand their decisions and practices in

shaping it.

This thesis is concerned with women’s body modification as a taken-for-granted

aspect of the social regulation of women’s bodies within a narrow definition of what

constitutes an acceptable feminine appearance. Though rarely explicitly defined, this

appearance is body and facial hair free, slim, toned, pore and blemish free (wearing

makeup), and dressed appropriately for any context. This appearance is reinforced

through the celebration of certain women’s appearance and the derision of others in

the public eye, as discussed above. In my thesis I therefore seek to understand how

women negotiate societal expectations of acceptable feminine appearance in their

everyday lives. To do this I analyse young women’s articulations of their motivations

to engage in body modification across their life course. Their relationship to these

practices and the level of agency which they think they have in these actions will be

analysed specifically for the school years, university and their entry into the world of

work.

My thesis is divided into six chapters. In the rest of this introduction I examine the

existing literature on body modification, providing a historical perspective on non-

feminist and feminist work on this topic. I shall assess where the literature

16

understands women to get their body modification ideas from and perceptions of

how women are influenced in this. I will highlight how my research fits into the

existing scholarly discussions and outline the gaps which it fills. Following this the

methodology chapter will explain my approach to conducting the empirical research

for this study and the methods I used. This shall include reflections on my personal

relation to this topic and its influence on the research.

The chronological analysis of my empirical data is split into three chapters which are

structured across three consecutive life phases. These are: ‘Learning to Follow: First

and Early Experiences of Body Modification’, ‘Adapting to New Environments:

University and Young Adulthood’ and ‘Changing Expectations: The World of Work

and Beyond’. I will analyse how and why body modification is begun and altered

across time, linking body modification to the development of women’s gendered

identity.

In Chapter 3, ‘Learning to Follow: First and Early Experiences of Body

Modification’, I analyse my participants’ initial engagement with body modification

and the development of these practices through the school years until university. In

Chapter 4, ‘Adapting to New Environments: University and Young Adulthood’, I

focus on the impact of university life on my participants’ practices. Changes as well

as continuities in methods and motivations are examined. In Chapter 5, ‘Changing

Expectations: The World of Work and Beyond’, I look at the role of body

modification in the lives of my participants as they entered their careers and the

influence of this environment on their practices. This chapter also considers

participants’ expectations of body modification in their future life, both in the near

future as well as during later life. In the conclusion I draw together the findings of

my empirical research. I demonstrate the importance of lifecycle and social context

to body modification development and the crucial and gendered relationship of these

practices and appearance to women’s identity. I shall also consider the findings of

my research in comparison to the stance previous literature has taken on where

women get their ideas and motivations for body modification from. In my

participants’ narratives their motives for engaging in practices of body modification

are complex and contradictory. They to some extent contradict third-wave

feminism’s notions of choice and agency. Certain factors influenced women’s

17

reasons for undertaking body modification at each of the three life stages. These

factors challenge some of the dominant ways that body modification has been

understood, especially by third-wave feminism.

Literature Review

In this section I assess the existing literature on body modification and the place of

my research within it. I begin with a brief assessment of empirical research on

women’s body modification. Following this I give an overview of the current

literature on body modification written from a non-feminist perspective; this will

include texts from popular culture, the medical sciences and work on consumption as

well as child development studies. Next I contemplate the position of the body in

feminism. Following on from this I give a brief historical overview of feminist

engagement with body modification. Most critical and gender-aware engagement

with body modification has come from feminist scholars and a feminist perspective.

This is the perspective which I personally and theoretically take and so it is crucial

for my own work to be contextualised within this field. Finally I will discuss the gaps

in the current research on body modification and how my work fits into these.

Empirical Research

I begin this literature review with a brief discussion of recent empirical literature on

body modification. While the majority of the literature I discuss in this chapter as a

whole is based on empirical research, in this section I will specifically assess what is

already know about women’s actual body modification practices. Given the age of

my participants (18-25) and the year in which I carried out my research (2012), I

shall be focusing on literature published from 2000 onwards. This focus ensures that

the body modifications discussed are relevant and comparable in timeframe to my

participants’ own engagement in such practices.

Empirical research on body modification from 2000 onwards has focused

predominantly on practices that are – in popular culture - considered extreme,

invasive or damaging to one’s health. Practices such as cosmetic surgery, extreme

18

dieting or exercise, eating disorders and tanning have received the most attention

(Bolton, Pruzinsky, Cash et al 2003; Didie and Sarwer 2003; Brӓnstrӧm, Ullén and

Brandberg 2004, Sawer and Crerand 2004; Henderson-King, Henderson-King 2005;

Soest, Kvalem, Roald, et al 2009; Cho, Lee, Wilson 2010). Reflecting this, in

assessing what is known about women’s body modification practices this section

does not discuss all possible practices but instead highlights the dominant picture that

emerges in the existing research.

A significant percentage of research addressing the question of what is known about

women’s actual body modification comes from a medical perspective. Knowledge on

the prevalence of practices in a given population is often from this field of research,

providing particular statistics with a national or international scope. Medical research

into body modification is focused on those practices considered risks or damaging to

health such as eating disorders or cosmetic surgery, with an aim to inform medical

guidelines and policy. Press releases from The British Association of Aesthetic

Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS) are a good and frequently cited example of this. Based on

statistics which represent the vast majority of NHS-trained consultant plastic

surgeons in private practice these releases usually document cosmetic surgery trends

in the UK on a yearly basis. This research shows that in 2013 50,122 cosmetic

surgery procedures were undertaken in the UK. Of those, women accounted for 45,

365 of the procedures (nine in ten) which was an increase of 16.5% on 2012. Of the

cosmetic surgery undergone by women in the UK in 2013, breast augmentation

10

was

the most popular with 11,123 procedures being undertaken (up 13% on 2012),

followed by blepharoplasty

11

with 6,921 (up 14% ), then face and neck lifts at 6,016

(up 13% ), 4,680 breast reductions (up 11%), 3,841 rhinoplasty

12

procedures (up

19%), 3,772 liposuction procedures

13

(up 43%), 3,343 abdominoplasty

14

operations

(up 16%), 3,037 fat transfer procedures (up 15%), 1962 brow lifts (up 18%) and

finally 670 procedures otoplasty

15

(up 19%) (British Association of Aesthetic Plastic

Surgeons 2014). The demographic breakdown of women who have cosmetic surgery

10

Breast augmentation is the surgical enlargement of the breast.

11

Blepharoplasty is the surgical repair or reconstruction of an eyelid.

12

Rhinoplasty is surgery to reshape the nose.

13

Liposuction is a technique used to remove fat from under the skin by suction.

14

Abdominoplasty is the removal of excess skin and fat from the middle and lower abdomen in order

to tighten the muscle of the abdominal wall making the abdomen more firm and thinner.

15

Otoplasty is the surgical reshaping or reconstruction of the outer ear.

19

reveals that teenagers are usually ‘preoccupied with unsightly moles, breast reduction

or rhinoplasty, those in the middle bracket - 25 to 45 - generally ask for body/trunk

surgery (liposuction, abdominoplasty), and older patients want facial rejuvenation’

(British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons 2005). In contrast to media

portrayals, which are directly challenged by these findings, this research also

demonstrates that the percentage of teenagers (those eighteen and younger) having

cosmetic surgery has not increased and remains low (British Association of Aesthetic

Plastic Surgeons 2005, 2008).

Women’s motivations to undertake cosmetic surgery, their experiences of this

practice and the after-effects of surgery have also been investigated. Negative ‘body

image’, a high investment in physical appearance and the gendered nature of

appearance value and expectations are repeatedly identified as the dominant factors

in women’s decisions to engage in cosmetic surgery (Bolton, Pruzinsky and Cash et

al 2003; Didie and Sarwer2003; Sarwer, LaRossa, Bartlett et al 2003; Frederick,

Lever and Peplau 2007; Markey and Markey 2009).

Prevalence figures about eating disorders, disordered eating, and extreme dieting and

exercise, particularly at a national level, also predominantly come from research

from a medical perspective. Eating disorders are known to be on this increase in the

UK and western countries more generally (Adams, Sargent, Thompson, et al 2000;

Hoek 2002; Cervera, Lahortiga, Angel Martínez-González, et al 2003; Gilbert and

Meyer 2005; Micali, Hagberg, Petersen, et al 2013; Kelly, Vimalakanthan and Carter

2014). The most reliable recent sources on eating disorder prevalence in the UK

found that in the general population aged over sixteen 6.4% of adults have an eating

disorder (Bebbington, Brugha, Coid, et al 2009). Women were more likely (9.2%)

than men (3.5%) to screen positive for an eating disorder (Bebbington, Brugha, Coid,

et al 2009). Age has also been shown to be a significant demographic factor in eating

disorder prevalence, with one woman in five aged 16-24 screening positively,

compared with one woman in a hundred aged 75 and over (Bebbington, Brugha,

Coid, et al 2009). Similarly Micali, Hagberg, Petersen, et al (2013) found adolescent

girls aged fifteen to nineteen to have the highest incidence of eating disorders while

Micali, Ploubidis, Stavola, et al (2014) reported that in their study of 7,082

adolescents aged 13 years 63.2% of girls were afraid of gaining weight or getting fat

20

and that a further 11.5% were extremely afraid or terrified of gaining weight or

becoming fat. In addition food restriction at a high level was reported by 2.4% of

girls, a high-level exercise for weight loss by 3.8% of girls and purging (self-induced

vomiting and use of laxatives for weight loss) by 0.23% (Micali, Ploubidis, Stavola,

et al 2014). Low self-esteem and low self-compassion were repeatedly indicated in

this research as characteristics positively correlated with the likelihood of women

having eating disorders or disordered eating (Gilbert and Meyer 2005; Kelly,

Vimalakanthan and Carter 2014).

Other practices considered damaging to health or extreme have also received a

notable amount of attention, in particular the use of sunbeds, and piercing and

tattoos. Sunbed use has increased in Europe, Australia and the USA since 2000 and

teenage girls and young women in their twenties are those most likely to engage in

this practice (Geller, Colditz, Oliveria, et al 2002; Demko, Borawski, Debanne, et al

2003; Lazovich, Forster, Sorensen, et al 2004; Køster, Thorgaard, Clemmensen, et al

2009; Mowen, Longoria and Sallee 2009; Diehl, Litaker, Greinert, et al 2010). While

in some cases a lack of knowledge on the dangers of sunbed use has been found to

contribute to women’s engagement in this practice, the majority of research suggests

that most women engaging in this practice are aware of the associated risks but

prioritise the appearance of tanned skin and following norms in peer behaviour over

health (Dennis, Lowe and Snetselaar 2009; Dodd, Forshaw and Williams 2013; Lee,

Macherianakis and Roberts 2013).

Women’s engagement in piercings and tattoos has been predominantly researched

simultaneously with the increase in both practices (Mayers and Chiffriller 2002;

Mayers, Judelson, Moriarty 2002; Armstrong, Roberts and Owen 2004; Bone,

Ncube, Nicholas, at al 2008). Piercing is more common than tattoos, particularly

among women who are more likely than men to engage in this practice (Mayers and

Chiffriller 2002; Mayers, Judelson, Moriarty 2002; Armstrong, Roberts and Owen

2004). Younger women are the most likely to have body piercings, as exemplified by

Bone, Ncube, Nicolas, et al (2008) who analysed the prevalence of piercing at sites

other than the earlobe, where nearly half of women aged 16-24 reported having a

piercing. The motivation to engage in both of these practices appears to be focused

on fashionable appearance and identity (Atkinson and Young 2001; Armstrong,

21

Roberts and Owen 2004). Women’s choice of tattoos has been found to be based on

gendered norms, with women predominantly choosing tattoos culturally understood

as conforming to a feminine identity in western countries (Atkinson 2002).

Empirical research on mundane and everyday practices such as makeup and hair

removal has been undertaken, but not to the same degree as research focusing on the

more extreme practices previously discussed in this section. Figures regarding the

prevalence of women’s use of this category of body modification are therefore not

very readily available. The exception is commercial market research providing sales

figures of certain products used in body modification. Hair removal is known to be a

normative practice engaged in by a large majority of women in western countries

such as the UK, Australia and the USA (Tiggemann and Lewis 2004; Toerien and

Wilkinson 2004; Toerien, Wilkinson and Choi 2005; Tiggemann and Hodgson

2009). Tiggemann and Hodgson (2009) found that 96% of Australian female

undergraduate students in their study (235 participants) engaged in body hair

removal regularly, giving similar results as a previous study of Australian

undergraduate students where 98% of women were found to regularly remove body

hair (Tiggemann and Lewis 2004). In a larger study in the UK Toerien, Wilkinson

and Choi (2005) found that over 99% removed some body hair. Looking at a wide

range of body hair removal practices of both women and men in New Zealand, Braun

and Terry (2013) also found female body hair removal to be a highly normative

practice and discovered that the vast majority of their participants (89%) deemed it

unacceptable for a women to leave body hair in its natural state (Braun and Terry

2013). The dominate reasons reported as key motivational factors in women’s

decision to remove body hair were social norms and attractiveness, with only 5%

suggesting that hair removal was done out of personal preference (Braun and Terry

2013). Similarly Braun, Tricklebank and Clarke’s (2013) investigation into the

removal of pubic hair removal found it be a normative and gendered practice. More

pressure was reported as existing on women to regularly remove pubic hair to be

attractive and to keep their pubic hair invisible (visible pubic hair was reported as

being socially unacceptable) than for men (Braun, Tricklebank and Clarke 2013).

While the rhetoric of choice was frequently used by participants describing women’s

decisions to engage in body modification, this choice featured as one limited by

feminine norms and heterosexual gender expectations. Avoidance of hostility and

22

stigma were the predominant motivations for women who carry out this practice on a

regular basis (Toerien and Wilkinson 2004; Hodgson and Tiggemann 2008; Fahs

2011; Smolak and Murnen 2011; Braun and Terry 2013; Braun, Tricklebank and

Clarke 2013). Body hair removal is a highly gendered practice necessary for a

woman to meet feminine norms.

Makeup, like hair removal, is a mundane, everyday and pervasive practice of body

modification engaged in by women. Despite this, very little research has been

conducted prior to and since 2000 on the prevalence of women’s engagement in this

practice or their motivations for doing so. Market research on the consumption of

makeup and cosmetics does however demonstrate how prevalent this practice is

within the UK. In 2012, 546 million pounds were spent on facial makeup which

accounted for 39% of cosmetics sales. Eye makeup represented the second-largest

subsector, accounting for 32.5% of the cosmetics sector, followed by lip products

(16.5%) and nail products (12%) (Delino 2014). The small amount of empirical

research available demonstrates that while makeup use can be pleasurable, many

women who use it view these items as essential everyday products (Cahill 2003;

Korichi, Pelle-De-Queral, Gazano, et al 2007; Delino 2014). The use of makeup has

also been found to be significant in adolescent girls’ perceptions of transitions from

childhood to adulthood (Gentina, Palan and Fosse-Gomez 2012). It is a practice

continued throughout women’s lives into old age (Clarke and Griffin 2007).

Motivations to engage in this practice are reportedly based on dominant femininity

norms and understandings that doing so will result in positive perceptions of

attractiveness and capability from others (Cahill 2003; Korichi, Pelle-De-Queral,

Gazano, et al 2007).

Hair styling and colouring are also mundane and everyday practices that women are

known to begin usually at a young age (Weitz 2001; Clarke and Griffin 2007).

Motivations to engage in these forms of body modification are reported as similar to

those around eye make-up, being based on perceptions of normative femininity

and/or identity presentation (Weitz 2001; Clarke and Griffin 2007).

Closely tied in with makeup and hair styling are fashion choices women make in

relation to both their dress and foot wear. This is a form of body modification is

23

found throughout women’s lives and once again is determined by how women want

to be perceived (Piacentini and Mailer 2004; Croghan, Griffin, Hunter, et al 2006;

Clarke and Griffin 2007; Raby 2010; Hockey, Dilley, Robinson, et al 2013). As in

the case of the other practices, the amount of empirical research carried out on these

forms of body modification is limited. The research which has investigated women’s

fashion has identified however that clothing and footwear are used by women to

fulfil multiple purposes, often based on the belief that clothing decisions will be read

as statements of identity. Guy and Banim (2000) for example discovered that their

participants used clothing to achieve satisfying images of themselves, identifying

their choices as creating, revealing or concealing aspects of their identity. Social

constraints on the clothing decisions they made were evident in women’s accounts,

as were attempts to subvert or challenge these constraints. In research on body image

the clothing women wear and the degree to which it meets their needs in a given

context has been found to impact on women’s experiences of their body (Tiggemann

and Lacey 2009; Tiggemann and Andrew 2012). Peluchette, Karl, Rust (2006) found

that their participants used work attire to ‘manage the impressions of others’ and

believed doing so had ‘a positive impact on workplace outcomes and self-

perceptions’ (58). They suggest that women undertake more ‘appearance labour’

than men. Age and body size are often factors influencing women’s sartorial choices,

and across life course (Frith and Gleeson 2008; Clarke, Griffin and Maliha 2009).

The participants in the work of Clarke, Griffin and Maliha’s study (2009), for

example, aged between seventy-one and ninety-three, argued that older women

should refrain from wearing bright colours and revealing or overly suggestive styles.

Clothing was reported as being used to mask changes in the body that were seen to

move it away from feminine ideals, such as weight gain, wrinkles, flabby skin and

shape change. Clothing styles were also used to ‘compensate for and conceal age-

related health issues’ (Clarke, Griffin and Maliha 2009: 718). Research into women’s

sartorial decisions makes evident that if a woman is perceived to have made ‘style

mistake’ through wearing clothes deemed inappropriate for her identity or social

setting, this can lead to stigma and negative reactions (Croghan, Griffin, Hunter, et al

2006).

Empirical research on women’s body modification illustrates the gendered nature of

these practices and the increasing engagement of women with them. A clear disparity

24

exists however between those practices of body modification which receive most

attention in the form of empirical research and the practices most prevalent in the

majority of women’s body modification regimes, as my own research demonstrates.

This is a disparity that my research addresses.

Non-Feminist Work on Body Modification

A plethora of literature exists on the subject of body modification. This forms an

expansive field of research that has developed over time, changing with the

technological development and popularisation of methods of bodily intervention,

such as Botox in 2002, and new cultural, medical and academic perspectives. As I

have begun to mention, body modification has a very prominent presence in popular

and mainstream culture, and this presence is gendered. Adverts for the tools,

treatments and products of body modification are almost unavoidable on television,

in magazines, on billboards, and on the side bars of Facebook

16

and email accounts.

A large percentage of pages in women’s magazines are dedicated to body

modification (Harbers 2013: 160; Tibbits 2013: 163; Turner 2013: 16-20; Elle 2014:

1-26, 29-31, 132-134, 284, 323-325; Beresiner 2014: 290; Lotringen 2014: 143-150).

Articles on and adverts for body modification also make regular appearances in both

broadsheet and tabloid newspapers. Television is equally inundated with

programmes specifically dedicated to the topic of body modification (for example:

SuperSize vs SuperSkinny (2014);

17

Secret Eaters (2014); Snog Marry Avoid

(2014);

18

How to Look Good Naked (2008)). The majority of television coverage of

this topic in all its forms is aimed at and features women. If a woman does not

undertake certain types of conventional body modification such as body and facial

hair removal the vitriolic reactions make evident the infrequency of this occurrence

and popular attitudes towards the image of an unmodified woman.

19

16

Facebook is an online social networking service.

17

Supersize vs SuperSkinny is a British documentary television series in which two extreme eaters,

one overweight and the other underweight, swap diets. Broadcast by Channel 4, Jan 2008 – March

2014, 8pm weekday evenings (seven series).

18

Snog, Marry, Avoid is a British reality television show that ‘makes under’ those seen to engage in

too much body modification and wear too much makeup/too little clothing, making their appearance

more acceptably feminine. Broadcast on BBC Three, June 2008-2014, weekday evenings (seven

series).

19

Following an appearance with hairy armpits on the red carpet at the 1999 London premiere of

Notting Hill Julia Roberts received well documented criticism (Winterman 2007) as did British singer

Pixie Lott when she appeared at the 2012 London premiere of The Dark Knight Rises with unshaven

25

A sense of moral panic about the rise in the use of body modification and the

perceived decrease in age of those that engage with it surrounds this topic in the

public imagination. Carpenter (2013), commenting on young women’s engagement

with plastic surgery, for example exclaims: ‘I can’t help being appalled at this.

Perhaps I am just getting old but I knew nobody in my twenties who’d “tinkered” or

had surgery and I barely know many now in my forties’ (27). This is particularly

apparent in magazine and news articles where young girls’ seemingly increased use

of body modification, especially invasive or potentially harmful methods such as

plastic surgery or eating disorders, are lamented and positioned as a cultural problem

(Carpenter 2012; Turner 2013; Buchanan 2014; Gibbons 2014). The UK government

has discussed and debated issues surrounding body modification, beginning a body

image campaign in 2010 (Government Equalities Office 2013a; Government

Equalities Office 2013b), creating an All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image

to carry out an inquiry on the subject (Central YMCA 2012; Featherstone 2012) and

holding a conference on body image on 30

th

September 2013. This group launched a

teaching pack for primary schools and a companion pack for parents on the subject

of body image (Media Smart 2011). On the whole government and policy interest

has focused on the female body, not the male, and in particular the young female

body. The sense of a need to protect girls from pressures which cause them to engage

in body modification and feel dissatisfied with their appearance is also echoed in the

Girl Guides’ decision to introduce a badge which is attained through a course on

body image (Girlguiding 2013). The Girlguiding organisation has, in addition,

conducted research into and run a campaign against body image dissatisfaction in

young girls (Girlguiding 2013).

20

The 2013 Poly Implant Prothèse (PIP) scandal also

resulted in the UK government increasing the attention it gives to body modification

and saw the subject feature in the ‘serious’ news (BBC News Health 2013; BBC

News Europe 2014; Chrisafis 2013a; Chrisafis 2013b).

21

armpits (Duncan 2012; Saunders 2012). The historian Professor Mary Beard has also received a large

volume of negative comments regarding her appearance due to her not wearing makeup or dying her

hair (Day 2013; Dowell 2013; Liddle 2013). A popular feature of magazines and blogs is to show

celebrity women without makeup, who are usually mocked for their unkempt appearance.

20

The Girl Guides is a movement in scouting originally, and still largely, for girls

(http://www.girlguiding.org.uk/home.aspx). Badges are collected as medals or rewards for carrying

out certain activities or achieving a task.

21

PIP had used unapproved in-house manufactured industrial-grade silicone instead of medical-grade

silicone in the majority of its implants and an unusually high number of rupture rates were reported.

This led to a flood of legal complaints and the company's bankruptcy. In many countries women with

these implants were advised to have them removed.

26

Economic evidence highlights the pervasive presence of body modification in

contemporary Britain. Despite the recession and current economic climate, the body

modification industry in its various categories has on the whole continued to grow

(British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons 2014). Reports also suggest that

despite the vast majority of people being economically worse off as a result of the

recession (women it should be noted are proportionally hit harder by the recession

(Women’s Budget Group 2013)), the percentage of income spent on body

modification has increased (Cosmetics Europe 2012; Key Note Publications 2013;

Mintel 2013). In the consumption of body modification practices, tools and products,

women are the majority consumers (Key Note Publications 2013).

Beyond popular culture, much of the literature which focuses on body modification

from non-feminist perspectives approaches the topic from a medical angle. This

literature centres on finding causes or behaviour characteristics which might be

responsible for the engagement in these practices. The literature, because of its

medical perspective, is on the whole only interested in practices or procedures with

medical implications, usually cosmetic surgery, some forms of eating disorder or

tanning for example (Sarwer, Wadden, Pertschuk, et al 1998; Brӓnstrӧm, Ullén and

Brandberg 2004; Sarwer and Crerand 2004; Henderson-King and Henderson-King

2005; Soest, Kvalem, Roald, et al 2009; Cho, Lee and Wilson 2010). The practices

discussed in this literature are positioned as a medical concern, illness or disorder

(McCabe and Vincent 2002; Fairburn and Brownell 2002; Allen, Byrne, Oddy, et al

2014). The everyday mundane practices of most women’s beauty regimes are rarely

acknowledged and practices are predominantly considered singly, not as part of a

regime alongside other forms of body modification. The medical literature tends to

have a focus on the individual and her problems that lead her to undertaking body

modification. The individual is pathologised. This pathologisation is founded in the

assumption that there is a ‘normal’ body and self-perception external to society and

its influence (Kater, Rohwer and Levine 2000; Grogan 2006; Liimakka 2014). The

other dominant strand of work on body modification and its causes, especially of

those methods thought to be health risks, focuses on the concept of body image

(Thompson and Stice 2001; Levine and Piran 2004; Bessenoff and Snow 2006; Jarry

and Kossert 2007). While women’s self-perception is still seen as one reason for

body modification, the cause of negative or distorted body images is understood, in

27

part, as the effect of socio-cultural influences on an individual. Images of ‘ideal’

women and bodies are seen as particularly problematic (Durkin and Paxton 2002;

Hargreaves and Tiggemann 2004). As investigations into what makes an individual

vulnerable to negative or distorted body modification illustrate though, it is still the

individual who is regarded as the locus of any ‘problem’, with the ‘cure’ focused on

fixing the individual rather than societal expectations (Yamamiya, Cash, Melynk et

al. 2005; Roberts and Good 2010; Halliwell 2013).

The subject of these texts is on the whole female. Men’s presence within this

literature has slowly increased over time, especially within the last ten years. Men are

still however in the minority as the focus for this literature. When they do feature

they tend to be treated as anomalies or different from women. Male interest and

concern with body modification and body image is often presented as a new and

growing phenomenon (Grogan and Richards 2002; Frith and Gleeson 2004;

Frederick, Lever, Peplau 2007; Hargreaves and Tiggemann 2009; Vandenbosch and

Eggermont 2013). This is contrasted with the constant expectation of women’s

concern with the body, both in the past and present. This expectation in part feeds the

assumption of women’s vulnerability to body modification and engagement in

harmful practices. Male concern is, however, more problematised even when the

practices that are carried out are not perceived as harmful or unhealthy.

In the search to understand who engages in what, and why they do so, race

occasionally receives attention. Race features predominantly through the comparison

of different ethnic groups’ resistance or vulnerability to external pressure (Kaw 1993;

Klesges, Elliott, and Robinson 1997; Furnham and Husain 1999; Striegel-Moore,

Schreiber, Lo, et al 2000; Ball and Kenardy 2002; Talleyrand 2012; Watson, Ancis,

White, et al 2013). There is a strong tendency, both explicit and implicit, to treat

western culture as the reference point for anyone undergoing body modification,

especially surgery and weight loss practices (Kaw 1997; Rathner 2001; Spickard and

Rondilla 2007). This assumption has been challenged by some academics which I

shall discuss later in this chapter (Holliday and Elfving-Hwang 2012).

Another identity variable frequently discussed is age. Age features as a topic most

prominently in relation to age appropriateness and fears around young women’s

28

engagement with body modification in particular. Consideration of age centres on a

belief that specific age groups (usually young girls) are more at risk from disorders

relating to body modification, such as anorexia, than others (Hoek 2002; Dohnt and

Tiggemann 2005; Baker, Thornton, Lichtenstein, et al 2012). Concern about young

girls engagement in body modification often come out of understandings that certain

practices are only appropriate for certain age groups. Though the subject of research

is usually specifically identified, as most of this research is quantitative or survey-

based, there is little of the participants’ own voice within it or in-depth explanations

of their context. As a result, this literature is often blind to class and socio-economic

positioning and the intersectional nature of identity. The concept of embodiment also

rarely features in the medical literature. Body modification is positioned as

something done to the body rather than an embodied event, and is discussed very

much in terms of mind/body duality.

Inseparable from almost all body modification discussion is consumption. To engage

in nearly all practices of body modification a product or service of one type or

another must be purchased. Consequently, a large volume of research has been

undertaken and literature produced on consumption and body modification (Fung

2002; Murray 2002; Starr 2004; Croghan, Griffin, Hunter and Phoenix 2006;

Mowen, Longoria and Sallee 2009; Marion and Nairn 2011; Workman and Lee

2011; Yang 2011). This literature, often from a business perspective, predominantly

focuses on what is being purchased, by whom, and why. From a more sociological

perspective, some work does focus on identity and consumerism however (Mowen,

Longoria and Sallee 2009; Narayan, Rao and Saunders 2011; Yang 2011). Most of

this research is quantitative and based on statistics, as knowledge about who buys

what and why is sought on a scale useful for marketing and predictions of

consumption patterns. A considerable amount of attention is also given to the neo-

liberal context of the west (and its spread beyond the west) and its role in

consumption practices, particularly in relation to identity formation (Murray 2002;

Edmonds 2007; Xu and Feiner 2007; Doyle and Karl 2008; Sherman 2008; Leve,

Rubin and Pusic 2012; Workman and Lee 2011; Luo 2013). Changes to consumption

practices in western countries are discussed, as are those of countries where

consumption has been severely restricted or state regulated in the past such as in

China and Russia (Hopkins 2007).

29

Often touching on issues of race and consumption, child development studies has

produced a considerable volume of work on body modification (Adams, Sargent,

Thompson, et al 2000; O’Dea and Caputi 2001; Gillison, Standage and Skevington

2006; McSharry 2009). Here a gender perspective is frequently taken, but unlike in

the two aforementioned fields of research, this is not limited to who engages in what

practices. Within child development studies the impact of gendered development on

body modification practices is a substantial field of research. The focus of this

literature is usually on young and teenage girls, though increasingly boys’

engagement with body modification features (Grogan 1999; Galilee 2002; Grogan

and Richards 2002; Lowry, Galuska, Fulton, et al 2005; McArdle and Hill 2007).

What practices children engage in as they develop, their motivations, and the impact

of this engagement on their lives is the predominant investigative focus of this work

(Herbozo, Tantleff-Dun, Gokee-Larose, et al 2004; Wills 2005; McSharry 2009;

Karupiah 2013). A discussion of why (usually assumed as a fact) girls engage in

body modification at a younger age and in greater volume than in previous

generations runs constantly through this literature. Practices which are regarded as

problematic, such as eating disorders, dominate the discussion (Kotler, Cohen,

Davies, et al 2001; McCabe and Vincent 2002; Martin 2007). Girls are presented as

at heightened vulnerability to external pressures compared to other groups (both of

gender and age) and, as a result of the combination of their age and gender, at risk of

engaging in dangerous practices (Fombonne 1995; Wertheim, Paxton, Schutz, et al

1997; Grogan 1999; Bloustien 2003; Lipkin 2009). Brumberg (1997) for example

argues that ‘girls today make the body into an all-consuming project in ways young

women of the past did not’ (xvii) and that ‘adolescent girls today are more vulnerable

than boys of the same age to eating disorders’ (xxiii). Martin (2007) contends that in

the contemporary west we ‘live in a time when getting an eating disorder, or having

an obsession over weight at the very least is a rite of passage for girls’ (1). The

concept of agency is given little thought in these arguments. Practices which are seen

as unproblematic or highly normative are also neglected.

In all of this there is little, if any, acknowledgement of work on body modification in

the social sciences, humanities or feminism. Despite the great volume of work

produced in the latter three fields, medical, consumption and child development

research is rarely interdisciplinary in its approach to this topic. As a result their

30

analyses are limited and non-holistic. Throughout these fields of research people

specialise in particular methods and usually a specific event or context. This

contrasts with my own research. My aim is to look at a wide range of practices and

widen the gaze of how body modification is investigated. What the literature

discussed so far has in common is that the practices it considers are all either highly

invasive or highly modificatory of the body. But this is not necessarily the

experience of most people in the mundane day to day context, and that is what I am

interested in.

Feminist Approaches

The Body in Question

Before I consider feminist engagement with body modification directly, I am going

to begin this section by reviewing the position of the body in feminist literature. This

includes both how the body is conceptualised and whose bodies are the subject of

discussion. How the body is conceptualised is intrinsic to how practices of body

modification are understood, for these practices are inextricably tied to the body

itself. The position of the body, and the volume and type of focus it has received in

feminism and related disciplines, has altered considerably over time. I am not able to

give a comprehensive and inclusive history of this change but instead will provide a

context to the position of the body, in particular the female body, in feminist

literature, as this relates to my research.

In the 1990s a new field of studies of the body appeared which was often highly

theoretical, such as the work of Grosz (1990), Shildrick (1996), Martin (1987 [1989])

and Davis (1995). A proportion of this work came out of philosophical

considerations about how we think about the body and corporeality, but it did not on

the whole engage with body modification directly or consider how women alter their

bodies to fit in with societal expectations. Instead this literature was concerned with

the body as a bounded object and the relation between the body and identity. This

marked a conceptual split away from feminist approaches in the 1970s where the

focus had been on female bodily specificity and the difference between the male and

female body. This new field of studies instead centred on the question of how we

31

think about the body as an entity. This work was characterised by the rise of theory

which questioned fixed identity and an engagement with the ways the body had been

constructed as a function of the sciences’ ways of articulating the body. Two

dominant strands emerged, one concerned with questioning traditional philosophical

discourses on the body (Grosz 1990; Shildrick 1996) and the other with rethinking

the medicalisation of the body (Martin 1987 [1989]; Davis 1995; Oudshoorn 1990).

Both of these strands aimed to re-think the female body but neither dealt with female

appearance. This latter concern would develop out of work predominantly on eating

disorders (which I discuss later in this chapter).

This new field of work can be seen as coming about in part because of two main

developments. Firstly, as a reaction to new and developing biological technology,

resulting in the rethinking of the female body and its possibilities (Martin 1987

[1989], 1991, 1992, 1994, 1999; Davis 1995, 1997, 1999) and how scientific

discourse and practices effect how we think about the body; secondly, this new field

of studies was in part an answer to what was happening in mainstream sociology in

relation to the conceptualisation of the body at the time. From the 1990s a trend

towards bringing the body back into mainstream sociology had occurred. This has

been called the corporeal turn and saw increased attention given to the body itself

with an emphasis on the materiality or corporeality of the body (Featherstone,

Hepworth and Turner 1991; Shilling 1993; Crossley 1995a, 1995b).

Feminists began to critique certain discourses of embodiment, arguing that science

produces particular ways of constructing the body, and illustrating the connection of

scientific knowledge to social and cultural elite groups. Focusing on embodied

experience, the anthropologist Emily Martin (1987 [1989], 1991, 1992, 1994, 1999)

approached the subject of the body from this perspective. Martin’s work explored

how cultural perceptions and representations of knowledge of the body and certain

bodily processes effect women’s bodily experience. In The Woman in the Body (1987

[1989] Martin, for example, argues that biomedical discourses on female

embodiment – in particular menstruation, childbirth and menopause – give a

medicalised and scientised account, informed by industrial capitalist modes of

production. She argues that the metaphor of labour used for child birth dehumanises

the experience, the woman not being taken into account as a human but only as the

32

uterus, acknowledged as a tool to provide doctors with a new product. Martin

suggests that as forms of social organisation vary, so do scientific and biomedical

explanations and images of the body. She illustrates in other work (1991) how

stereotypes of gender inform biological knowledge, in particular utilising the

example of the passive egg and the active sperm. Martin claims that ‘becoming

aware of when we are projecting cultural imagery onto what we study, will improve

our ability to understand nature … [and] rob them of their power to naturalise our

social conventions about gender’ (501). She shows that current scientific literature is

gender-biased and disadvantageous to women, disconnecting them from their bodies

through mind/body dualistic metaphors. Martin’s work on the body came in the

midst of a rise in the development of biotechnology, in particular reproductive

technologies such as sonograms and in vitro fertilisation (IVF)

22

, and can be seen as

a reaction to these. These biotechnological developments placed greater emphasis on

the biology of women’s bodies and increasingly compartmentalised the body into

parts. In contrast, Martin sought to highlight the importance of the social for

embodied experience and knowledge.

Davis (1995, 1997, 2003), one of the only feminists engaging in this new field of

studies to directly discuss forms of body modification, also addressed the issue of

embodiment in relation to technological developments, most notably cosmetic

surgery. Davis (1995) considers the embodied experience of those who undergo

cosmetic surgery, acknowledging the new possibilities that such biotechnology offer

to women. Davis discusses cosmetic surgery as a dilemma, existing as part of

patriarchal medicalised conceptions of beauty, but providing women with an at times

welcome intervention in their identity. Davis argues that cosmetic surgery offers

women ‘different starting points’ and can ‘open up the possibility to renegotiate her

relationship to her body and construct a different sense of self’ (113). Extending

women’s realities beyond the biologically given, she sees such technologies as ‘a

strategy for becoming an embodied subject’ (1995: 96). Through looking at different

possibilities for embodiment Davis (1997) also highlights mainstream sociology’s

male-centric approach to understanding the body at the time. In particular she noted

22

The first successful birth of a child conceived by IVF occurred in 1978.

33

the treatment of bodies as generic, with the male body situated as the natural body to

which all others were compared.

As technological developments were occurring, so were developments in

sociological understandings of the body outside of feminism. The corporeal turn in

sociology brought with it certain dilemmas for feminist academics. From a feminist

perspective, the critique of mainstream sociology centred on the difficulty of

acknowledging the embodied corporeal body without compromising the social

construction of gender. As Anne Witz (2000) argues, ‘Women have been under

socialised and overwhelmingly corporealised in accounts of the social. The woman

in the body served as the foil against which a masculine ontology of the social was

constructed’ (Witz 2000: 2). Elizabeth Grosz (1990, 1994, 1995) sought to address

this problem through the creation of a model of corporeality where boundaries are

dissolved and where women’s experience is not reduced to the other, but instead

specificity and difference are acknowledged. In the creation of this model she

engaged with and in the debate over what constitutes a body, and crucially how to

acknowledge women’s corporeality without biological determinism. Grosz views

gender as a redundant category (1995) on the grounds that it is based on a

body/consciousness dualism. She was part of a feminist movement trying to reclaim

the body through making women’s experiences visible within sociological enquiry

without reducing women’s experience to the body, and particularly biology.

Margrit Shildrick (1996, 1997, 1999, 2002) similarly attempted to reclaim the female

body through destabilising masculinist perspectives on the body. Shildrick argued for

a conception of the body as fluid:

Both sociological and biological bodies are not given, but exist only in

the constant process of historical transformation … there are only hybrid

bodies, restless bodies, becoming-bodies, cyborg bodies; bodies, in other

words, that always resist definition… My argument is that boundaries are

fluid and permeable, not that they cease to exist altogether (Shildrick

1996: 9).

34

Shildrick uses bioethics as an example to contend that ‘material’ entities and

linguistic concepts are discursive constructions and in turn that biomedicine not

merely restores the body but constitutes it. The body for her is not a constant given

entity with stable boundaries but a fabrication, an ever-changing reality formed by

multiple discourses, a ‘leaky body’ (1997). She demonstrates how new technologies

aid the maintenance of the notion of a fixed material body through exploring how the

way technology is used is reliant upon and helps confirm social norms. Shildrick

highlighted the importance of the social in constructing perceived bodily realities.

Nelly Oudshoorn (1990, 2003) was another feminist at the time to argue this through

her work on the male pill. Oudshoorn (1990) examined the development of sex

hormones in laboratories, and cultural, scientific and policy work around the male

pill from the 1960s to the 1990s (2003). In both cases Oudshoorn argued the

importance of recognising science as part of the social, determined by social realities

and, significantly for feminism, social gender bias. She argues that because ‘the

subject of women and reproduction has been institutionalised in a medical speciality,

whereas the same processes in men have not been institutionalised, gender bias is at

the centre of the life sciences’ (1990: 25). Her discussion of the male pill illustrates

the gender bias in technological development, suggesting for example that this

contraceptive has not been introduced because of particular ideas about reproductive

responsibility. For Oudshoorn biotechnologies are not outside of the social. Their

development and use is defined by social priorities and understood possibilities.

It is important to know how the body is/was conceptualised in feminism to fully

understand feminist relations to practices of body modification, for they sit as

practices inseparable from both bodily materiality and the social. In this literature in

the 1990s the body is treated to a large extent as a depersonalised entity, almost as an

object, and the person that inhabits the body as a shadow figure in the background.