The

National

Summit on

Retirement

Savings

SAVER

June 4-5, 1998

Washington, DC

Final Report on ...

U.S. Department of Labor

This publication is available on

the internet at:

http://www.dol.gov/dol/pwba

For a complete list of publications

available from the Pension and

Welfare Benefit Administration,

call the toll-free Publication Hotline:

1-800-998-7542

This material will be made available

to sensory impaired individuals

upon request:

Voice phone: (202) 219-8921

TDD: 1-800-326-2755

This booklet constitutes a small entity

compliance guide for purposes of the

Small Business Regulatory Enforcement

Fairness Act of 1996.

The

National

Summit on

Retirement

Savings

SAVER

June 4-5, 1998

Washington, DC

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

SECRETARY OF LABOR

WASHINGTON, D.C.

September 3, 1998

To: President Clinton, the Speaker and Minority Leader of the U.S. House of Representatives, the Majority and

Minority Leaders of the Senate, and Chief Executive Officers of the States:

It is my pleasure to submit this report on the 1998 National Summit on Retirement Savings.

The Summit, held June 4-5, 1998, in Washington, DC, brought together leaders from both political parties, large

corporations and small businesses, labor organizations, and numerous groups involved with employee benefits,

personal finance and retirement issues. In accordance with the Savings Are Vital to Everyone’s Retirement Act of

1997 (P.L. 105-92), their mission was to determine how best to raise awareness of the need for pension and

individual savings so that working Americans and their families may enjoy a secure and comfortable retirement.

The Summit was historic in many ways. First, it was a truly bi-partisan effort to draw national attention to the need

to build a secure financial foundation for our country’s retirees. This was made abundantly clear during a keynote

session attended by President Clinton, Vice President Gore, House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Senate Majority Leader

Trent Lott, House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt and other Members of Congress. As Rep. Harris Fawell (R-

IL), the principal author of the SAVER Act, put it: “We were attacking problems not as Republicans or Democrats,

but to say ‘What can I do to help?”’

Over the course of the Summit, delegates identified a number of barriers that individuals and employers face in

saving for retirement. At the same time, delegates identified numerous meaningful steps that the government,

employers, the media, community organizations, schools, and others can and should take to build a secure retirement

for our nation’s workers. As reflected in this report, while there was extraordinary diversity in views on both the

barriers to retirement security and the ways to address the problem, delegates repeatedly returned to the theme that

retirement education will be a crucial element in any strategy to increase savings.

The gathering also represented a unique public-private sector partnership of leading organizations with specialized

expertise in retirement savings and a commitment to spreading an educational message about the need to prepare for

retirement. I believe that the success of the 1998 Summit was, in many ways, attributable to the collective

experience of our many private sector partners. In this regard, I would like to specifically thank the American

Savings Education Council, the Employee Benefit Research Institute, and the American Society of Pension

Actuaries and for their outstanding efforts in making the 1998 Summit a success.

Through the hard work of all Summit delegates and organizers, we have done much to move the issue of retirement

security to the forefront of the national agenda. Now the challenge for all of us is to spread the savings message, and

to share winning strategies that will inspire, convince and equip companies, organizations, communities and

individuals to take immediate action. As President Clinton said at the Summit, “This is a wonderful moment, but it is

a moment of responsibility that we dare not squander.” As provided in the SAVER Act, future Summits in 2001 and

2005 will measure our nation’s progress.

My sincere hope is that this report will serve as a catalyst to increase pension and individual savings so that all

working Americans and their families, regardless of age, nationality, or income level, can look forward to a truly

secure and dignified retirement.

Sincerely,

Alexis M. Herman

W

ORKING

FOR

A

MERICA

’

S

W

ORKFORCE

Table of Contents

Page

I. Introduction 1

II. The Current State of Retirement Saving and Education Today 3

III. Models for Educating the Public about Retirement Saving 8

IV. Break-Out Facilitators Reports: Barriers and Opportunities 13

Appendix 1: The Summit Agenda 33

Appendix 2: List of Appointed and Statutory Delegates 35

Appendix 3: Break-out Groups’ Full Listing of Barriers and Opportunities 47

I. Introduction

Americans must save more today if they are to realize the dream of a financially secure retirement

tomorrow.

That is the message of the first National Summit on Retirement Savings, held in Washington June 4–5,

1998. Convened jointly by President Bill Clinton and the bipartisan leadership of Congress in accordance

with the Savings Are Vital to Everyone’s Retirement Act of 1997 (SAVER) (PL 105-92), the Summit under-

scored the need to fortify the American system of employer-sponsored pensions, to extend pension coverage

to underserved groups—especially women, minorities and employees of small businesses—and to encourage

individuals to save more themselves.

Virtually every institution and individual in America can contribute to achieving these goals. “Each of us

has a role to play in meeting this great challenge,” said Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin. “Government can

take steps to encourage savings, as we are doing. Businesses can offer sound retirement plans for their

employees, and convey the importance of saving. And each of us as individuals can take steps to make the

most of the opportunities that make it easier to save.”

This report details many possible steps toward achieving the goal of a financially secure retirement for all

Americans. Not all of the delegates agreed on what steps to take. In fact, many proposals were controver-

sial. But of all the possibilities that were discussed, one theme stood out: We must do a better job of educat-

ing the public—employers and individuals alike—about the importance of saving and about the tools

available to ensure that we can afford to retire and remain financially independent. Too many individuals

and employers are simply unaware of the basic facts of life concerning retirement.

To increase public awareness about the retirement savings issue, the following were among the ideas

discussed:

• Enhancing the federal government’s educational efforts through programs such as the Department of

Labor’s Retirement Savings Education Campaign, which seeks to inform Americans about pension and

retirement issues, and other initiatives called for by the SAVER Act;

• Encouraging states to launch their own retirement-savings initiatives;

• Urging the media in all areas of the nation to assume a more active role in informing the public about

retirement savings;

• Calling on the private sector to support public-education campaigns, and;

• Urging employers to sponsor retirement plans and educate employees about the importance of retire-

ment saving.

These steps clearly represent a beginning and not an end. Delegates presented a wide range of approaches

to address retirement savings, including: (1) the need for legislative changes to encourage the creation of

employer-sponsored retirement plans; (2) the need to make pensions more portable and to place additional

focus on retirement savings for part-time and low-income workers, and (3) the need for a decrease in

1

2

income and payroll taxes or a significant increase in tax incentives to encourage greater savings. Some

possible strategies undoubtedly will prove controversial, and may conflict with other objectives. But the

Summit demonstrated that Americans believe the underlying goal—a secure retirement for all Americans—

transcends partisan politics. “Americans should be able to count on predictable and secure retirement

benefits for life,” said Vice President Al Gore. “We must ensure that dreams deferred never become dreams

denied.”

“This is something you won’t see very often,” noted Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott. “Here we are all

together—the legislative branch, executive branch, Republicans, Democrats, maybe even liberals, conserva-

tives, moderates and everything in between. This can be, may be, should be the beginning of doing some-

thing very important for this country.” As House Speaker Newt Gingrich stressed, “You know, having us up

here together is more than just symbolic. When we work together, good things happen.”

The stakes are high. The future of millions of working Americans—and their children—may be shaped in

important ways by what flows from the Summit and follow-up gatherings scheduled for 2001 and 2005. But

the time to start is now.

As President Clinton said, “We have an obligation to deal with this challenge, and deal with it now. And we

have an opportunity to do so.”

II. Current State of Retirement Savings and Education Today

The Summit rose out of concern over a simple but far-reaching fact: many Americans are not planning or

saving enough to be able to afford to retire.

The Challenge

Delegates, who received a background report summarizing 20 years of research on retirement finance,

reviewed the current state of saving during an opening plenary meeting. A presentation by the American

Savings Education Council Chairman and delegate Dallas Salisbury set the context for their deliberations.

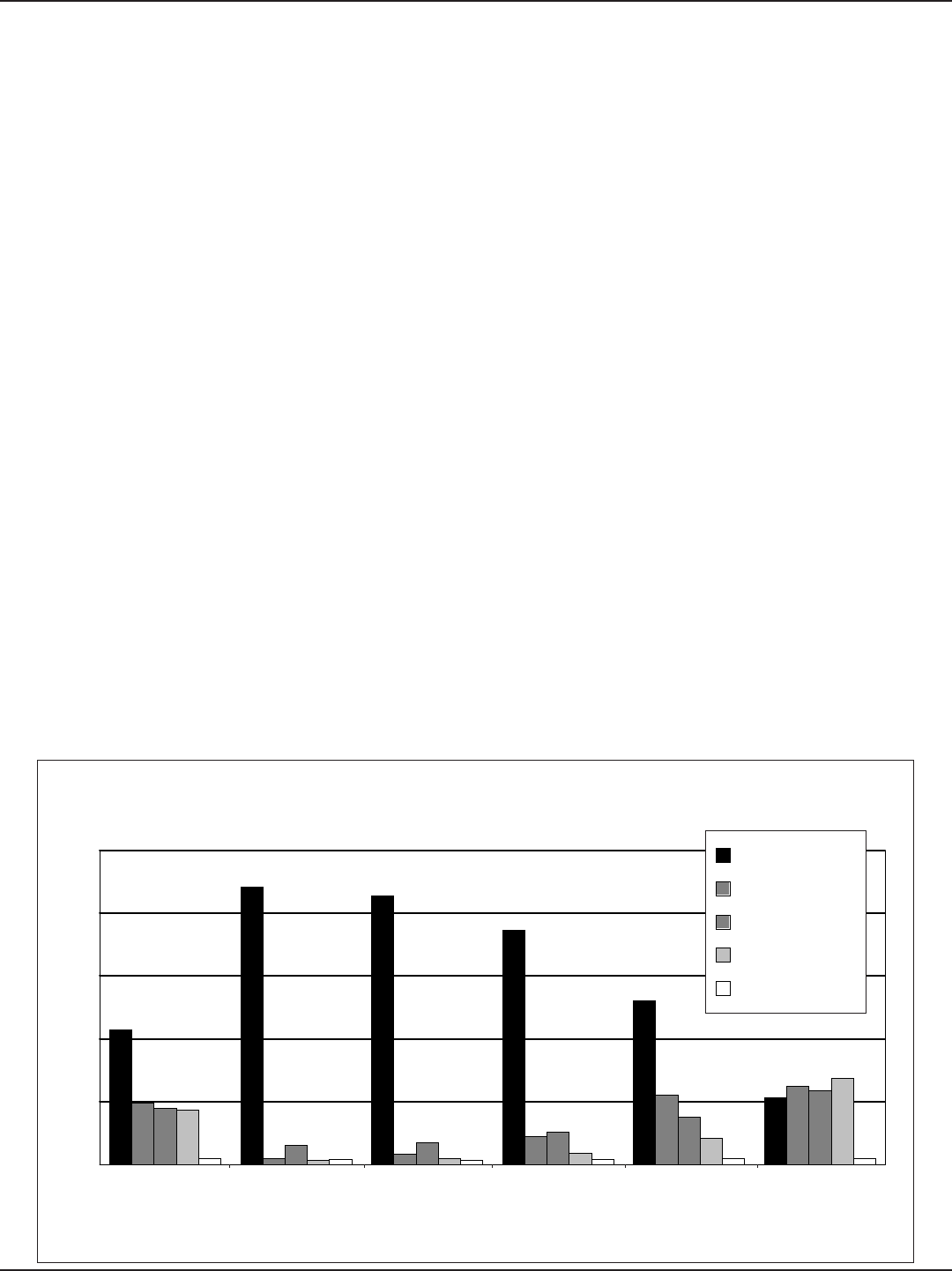

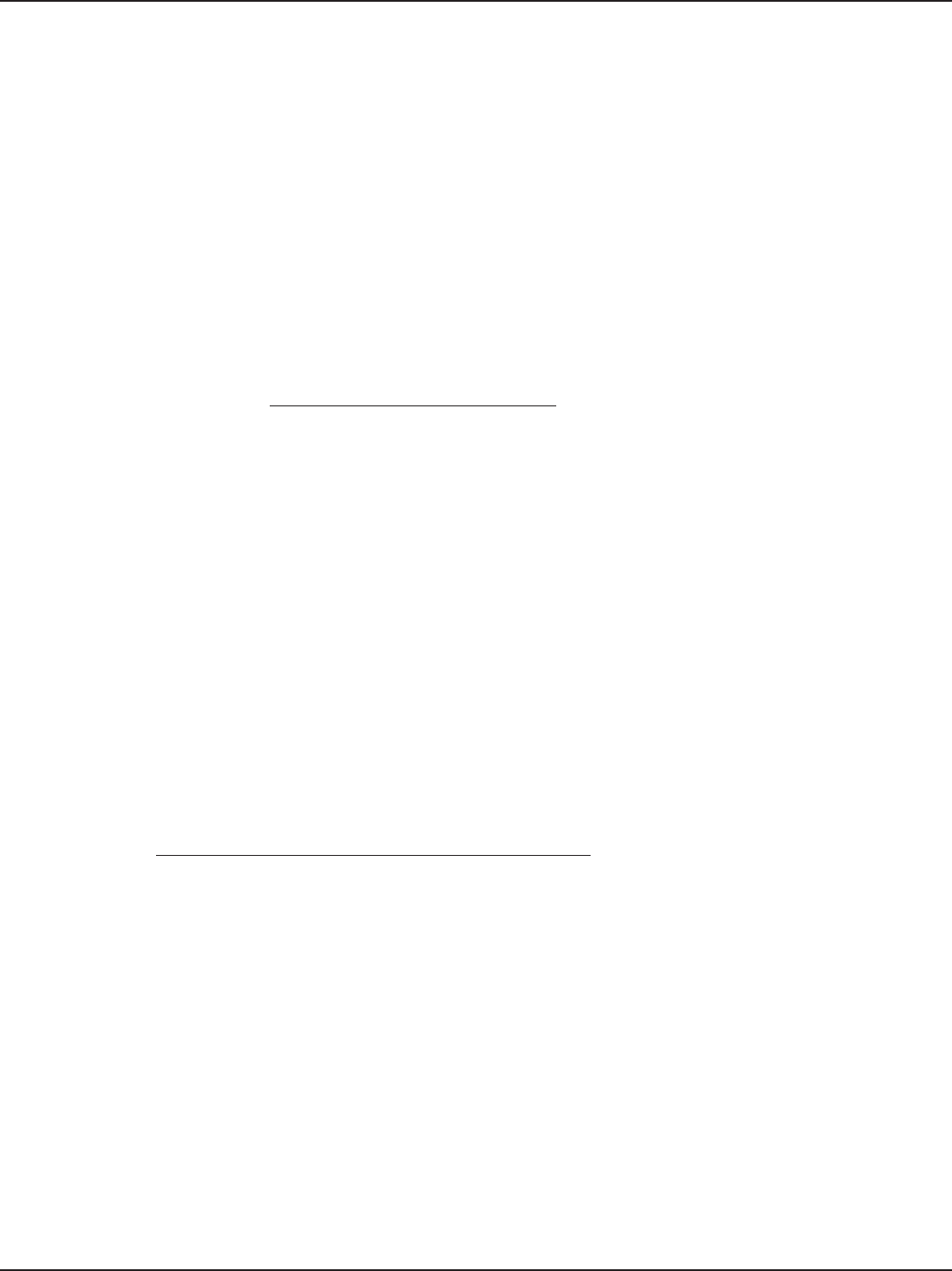

Chart 1 from the report and Salisbury’s presentation shows that employment-based pensions and personal

savings currently account for a small share of retirement income received by the majority of Americans.

Indeed, 80% of elderly Americans rely on Social Security for most of their retirement income, and the

lowest-income 40% of Americans depend on it almost exclusively. (In accordance with the SAVER Act,

Social Security reform was not a topic for the Summit, which focused on private pensions and individual

savings.)

Despite these figures, Social Security was never intended to serve as the sole source of income for retirees.

A person who earned $15,000 a year and retires in 1998 at age 65, for instance, can expect Social Security

to replace just one-half of his or her preretirement income. And the “replacement rate” drops steadily for

individuals in higher income brackets: an individual who earned $68,400 before retirement, for instance,

will receive the maximum $1,248 monthly benefit, but that will equal less than one-quarter of his or her

preretirement income.

Inadequate pension and personal savings may explain why many Americans look to retirement with consid-

erable uncertainty. “Savings, retirement and retirement security are some of the most important features of

life in America over a very long period of time,” stated Rep. Richard Gephardt (D-Mo). “All of us know that

there cannot be safe and secure retirement unless there is the ability to put away funds to save money

while one is working.”

Chart 1

Income of Elderly Individuals (Ages 65 and Older) from Specified Sources,

by Income Quintile, 1996

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute tabulations of the March 1996 Current Population Survey.

a

Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance.

Percentage

1

Lowest

($6,031 or lower)

2

($6,032–$9,316)

3

($9,317–$13,808)

4

($13,809–$22,253)

5

Highest

($22,254 or more)

Total

0

20

40

60

80

100

OASDI

a

Pensions and Annuities

Income from Assets

Earnings

Other

3

4

Reporting on the 1998 Retirement Confidence Survey, Mathew Greenwald, president of Mathew Greenwald

& Associates, told Summit delegates that 31% of current workers are “clearly worried” about their financial

prospects in retirement. Another 44% are only “somewhat confident.” That means they believe they will

have sufficient income if inflation remains subdued and they remain healthy—assumptions that will prove

unrealistic for many Americans, according to Greenwald. He noted, for instance, 40% of current retirees

had to leave work earlier than they had planned, many for health reasons. That leaves only about one in

four Americans who are very confident they will have enough money to live comfortably when they retire.

The Need for Education

While the large number of people who face retirement with trepidation is cause for concern, it is equally

troubling that individuals’ assessments are almost certainly uninformed. Greenwald noted that half of all

current workers have never tried to figure out what they will need when they retire. And, he added, previ-

ous studies suggest that half of those who try to make such calculations do not succeed in coming up with a

figure.

Moreover, Greenwald added, many people underestimate their life expectancy, which for today’s retirees

easily can stretch 30 or more years beyond the traditional retirement age of 65. He also said relatively few

people know the cost of long-term care, and therefore underestimate their retirement income needs.

In many cases, employers are as uninformed as employees, judging from the Small Employer Retirement

Survey conducted by Greenwald with the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) and the American

Savings Education Council (ASEC). Of the 35 million people employed in small companies, 26 million do not

have access to retirement plans at work. “Small businesses that do not offer plans exhibit real misunder-

standing of what is required,” Greenwald said. “Many think plans are more expensive than they have to be.

They do not understand they can set up a plan for less than $2,000, that they aren’t required to match

employee contributions or that they can share administrative costs with employees.”

Despite the clear importance of saving to ensure a retirement income beyond what Social Security will

provide, one worker in three is not setting aside any money personally for retirement, according to the

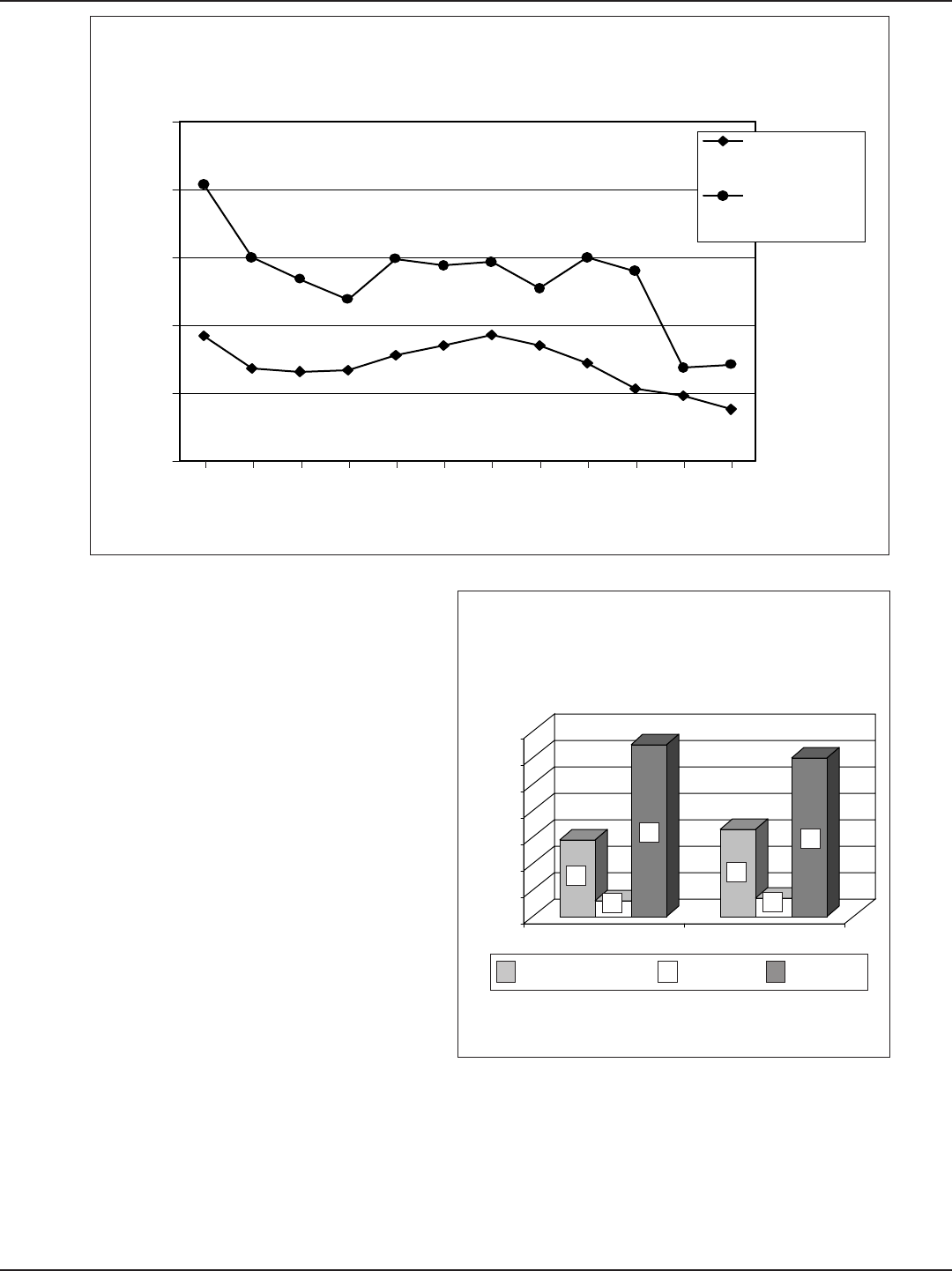

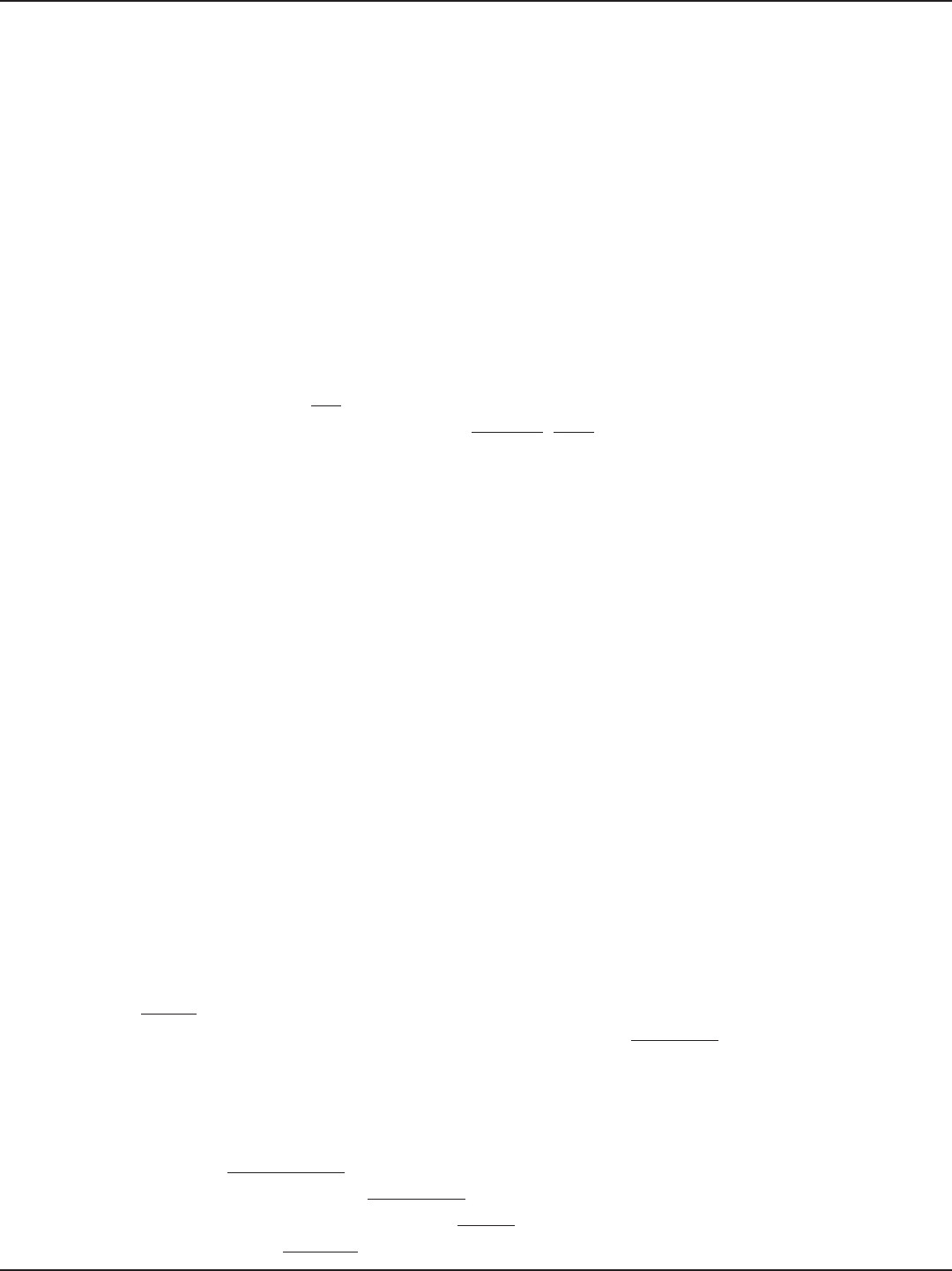

Retirement Confidence Survey. The personal savings rate is at or near a post-World War II low. (See Chart

2) Only 10% of eligible taxpayers are making tax-deductible contributions to individual retirement accounts

(IRAs). And just 40% of the individual distributions of pension funds made to job changers were rolled over

into tax-deferred retirement accounts, suggesting that many workers are not holding on to their retirement

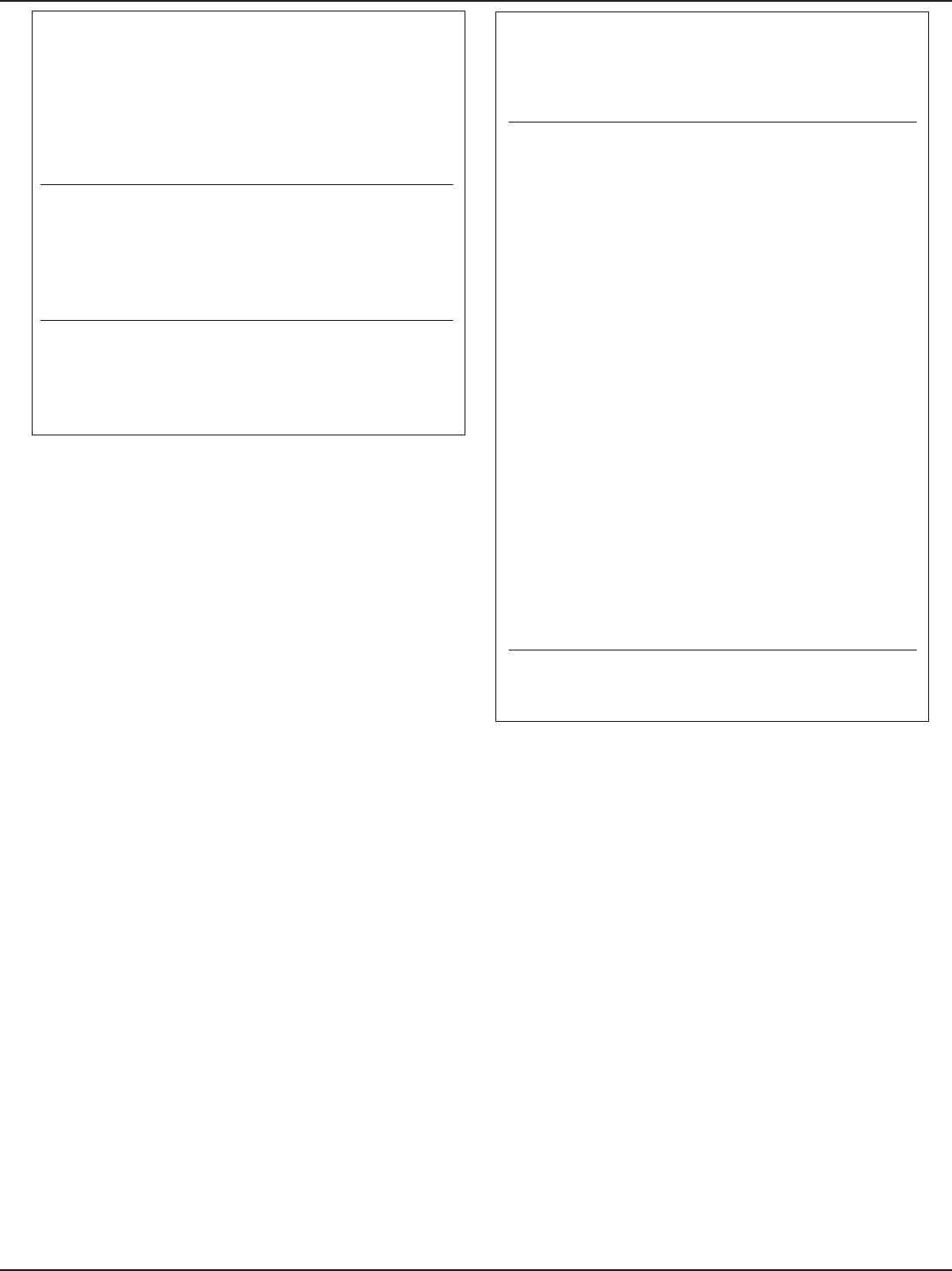

savings but rather are spending them for other, short-term purposes. (See Chart 3)

Most nonsavers say they have too many other financial responsibilities, but in many cases that is a myth,

he added. Over half of individuals polled in the Retirement Confidence Survey said they could afford to save

$20 more per week.

Consider this: if a worker starts saving $20 a week at age 30 and earns 10% on his or her investment, that

would add up to a retirement nest egg worth $310,000 by age 65.

The Role of Employers and Unions

While suggesting that individuals need to save for their own retirement, Summit participants stressed that

employers must continue to play a central role as well.

25

20

15

10

5

0

7.8%

8.5%

9.3%

8.5%

7.2%

5.3%

11.9%

14.9%

12.7%

9.2%

6.7%6.8%

6.6%

3.8%

4.8%

20.4%

7.1%

14.7%

15.0%

14.0%

14.4%

15.0%

13.4%

6.9%

Flow of Funds

Accounts Data

National Income

and Products

Accounts Data

1946 1950 1960 19651955 198019751970 199519901985 1997

Percentage

Year

Chart 2

Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Personal Income

Source: http://www.bog.frb.fed.us/releases/Z1/annuals table F.9 Derivations of Measures of Personal Savings.

Flow of Funds

Accouts Data

National Income

and Products

Accouts Data

Percentage of Distributions

Chart 3

Benefit Preservation among Job

Changers, by Percentage of

Distributions, 1993 versus 1996

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute and Hewitt

Associates tabulations of Hewitt Associates data.

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Rolled Over to Individual

Retirement Account

Rolled Over to

Qualified Plan

Took as Cash

Playment

1993

1996

29

6

65

33

7

60

5

Josephine Tsao, vice president for global benefits

and compensation for IBM Corporation, said

that role is changing though. In today’s complex

and highly competitive global marketplace,

“employer paternalism and altruism can no

longer be the sole foundation for employer-

sponsored retirement savings programs,” she

said.

Instead, she described the retirement system of

the future as a partnership between employees,

employers and government. Employees must

assume more responsibility, she said. Employers

must serve not simply as providers of benefits,

but as “contributors to and facilitators of”

individual savings efforts. And government must

provide both a foundation through Social Secu-

rity and a “stable framework” of rules that allow

employers to adjust their retirement plans to

meet competitive demands and employee needs.

This new partnership can work, Tsao argued. Fully 90% of IBM’s U.S. workforce voluntarily participates in

the company’s 401(k) retirement saving plan. Some 60% of their assets are invested in equities,

demonstrating that they understand issues such as long-term investment strategy. What’s more, 25,000

IBM employees have worked with outside experts to prepare individual financial plans, and 40,000 are

managing their own retirement accounts using the World Wide Web.

Table 1

Retirement Plan Sponsorship and

Participation Among Private Wage and Salary

Workers Ages 16 and Older by Firm Size

Firm Size

Sponsorship

Rate

Participation

Rate

Total number

of workers

Total 88,679,369 55.6% 40.7%

Fewer than 25 22,894,696 17.2 12.9

25–99 11,806,119 41.7 29.6

100 or more 46,986,404 79.4 58.9

Unknown 6,992,150 45.2 28.1

Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) tabulations of the 1993 Current

Population Survey employee benefits supplement.

6

“Flexibility, choice and control” are the watchwords for a successful employment-based retirement-savings

system today, Tsao suggested. And she concluded: “Together, we must educate our workforce, because

otherwise we will have a workforce that is ill-prepared for retirement and that will be dependent on social

programs. Both of these will hamper the competitiveness of our nation in the future.”

James Ray of Connerton Ray noted the role of unions and collective bargaining in expanding pension

coverage particularly for low and moderate wage workers, as well as providing education about retirement

needs. Emphasizing the need for continuity, Ray argued that traditional defined benefit pension plans, in

which employers guarantee retirement benefits based on salary and years on the job, should be the main-

stay of the retirement system. These plans best shield workers from risk, and unlike defined contribution

plans, enable plan sponsors to provide pension benefits based on years of service, can be used to mitigate

the effects of corporate down-sizing, and allow for post-retirement benefit increases, he argued.

But Ray also acknowledged the virtues of defined contribution plans, particularly as supplemental plans for

those workers who can afford to save. A combination of both defined benefit and defined contribution plans

would represent the “best of both worlds”—a “sound foundation,” guaranteed lifetime income and worker

control, he concluded.

Problem Areas

While saving for retirement is inadequate among all segments of the population, delegates focused espe-

cially on several groups that are particularly at risk, including:

Small Businesses. According to Summit background materials, 79% of all private wage and salary work-

ers whose employers have 100 or more workers have access to pension plans at work, compared to 42% of

workers in companies employing between 25 and 99 workers and 17% of workers whose employers have

fewer than 25 workers. (See Table 1)

Craig Hoffman, vice president and general counsel for Corbel & Co., said there are two basic reasons many

small businesses do not offer pension plans. First, many employees do not demand pension plans, at least

compared to cash compensation or health benefits. In addition, many employers worry about the cost of

employer contributions and the expense of administering pension plans.

Table 2

Mean Value of Pension Wealth for

Selected Wealth Deciles, 1992

1 $1,356 $42,312

3 $19,181 $93,920

7 $125,635 $142,981

10 $389,865 $161,605

Wealth

Decile

Pension

Wealth

Social

Security

Wealth

Source: Moore and Mitchell, 1998.

Note: In this table, wealth is the present value of all

defined benefit and defined contribution pension

accruals.

Table 3

Pension Participation Rates for Wage

and Salary Workers, 1993

All Workers

Total Men Women

Total 49% 51% 46%

Hispanic 32 32 33

African-American 46 46 47

White 51 55 47

Asian-American 41 41 41

Private-Sector Workers

Total 43 46 39

Hispanic 26 24 28

African-American 38 40 36

White 46 50 41

Asian-American 35 36 36

Public-Sector Workers

Total 71 80 74

Hispanic 72 82 74

African-American 71 65 76

White 78 84 74

Asian-American 70 67 68

Source: U.S. Department of Labor tabulations of the 1993

Current Population Survey.

7

Low-income workers. Dallas Salisbury, president

of the Employee Benefit Research Institute and

chairman of the American Savings Education Coun-

cil, noted that the nation faces “tremendous chal-

lenges” in helping low-income families accumulate

what they will need to retire.

According to figures in slides presented by Salisbury,

the 10% of families with the lowest income in the

U.S. have pension wealth worth, on average, $1,356,

and the present value of their Social Security ben-

efits is $42,312. In comparison, the wealthiest 10% hold pension assets worth an average of $389,865, and

the present value of their Social Security entitlements is $161,605. (See Table 2)

Women and Minorities. Ann Combs of William M. Mercer Companies, Inc., noted that women and

minorities on average are less likely to receive retirement income from pensions than white males.

Specifically, 32% of current female retirees received pension benefits in 1994, compared to 55% of male

retirees, and the average benefit for women was only half as large as that paid to men. At the same time,

32% of Hispanics received pension benefits, compared to 40% of African Americans and 52% of white

retirees. Not surprisingly, older women are twice as likely to be poor. Elderly African Americans are three

times as likely to be poor.

The problem, according to Combs, is that both groups tend to earn lower wages than white males and to

have shorter job tenures. That, in turn, reflects in large part the fact that these groups, especially women,

are more likely to work part time, and are disproportionately represented in the retail and service sectors

where relatively few employers offer pension plans and are less likely to belong to unions.

The challenge in meeting the needs of these groups, then, will be to expand the access to pensions available

among the employers where such workers tend to be clustered, Combs concluded. (See Table 3)

III. Models for Educating the Public about Retirement Saving

During the two days of the Summit delegates returned repeatedly to the need to educate individuals and

employers alike on the retirement-saving issue. Concerning individuals, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin

argued for a three-pronged educational strategy aimed at: encouraging those who are not saving at all,

particularly lower and middle-income workers, to start saving; teaching young people the value of saving;

and helping those who already are saving to understand how much to save and what vehicles for saving are

available to them.

Other delegates noted that educational strategies aimed at individuals must be tailored to reach different

groups, including minorities, women, low-income workers, and people who do not speak English as a first

language.

Employers need to be better informed as well, the delegates agreed. Too many employers, especially small-

business owners, do not currently understand the options they have—some quite inexpensive—to sponsor

retirement plans for employees.

In a plenary session on the second day of the Summit, the speakers discussed five models that exemplify

the kind of public and private commitment required to get working Americans on track toward financially

secure retirements. David Walker, moderator of the panel, noted that, “The rapid movement by the private

sector to defined contribution type vehicles and voluntary savings arrangements serves to increase the

importance of retirement planning and investment education.”

Retirement Savings Education Campaign

Launched by the U.S. Department of Labor in 1995, this public-information project has grown from 65

public- and private-sector partners to over 250 today. The Department has distributed more than 25 publi-

cations geared to educate individuals and employers about savings and how to protect pension benefits. In

addition, it has produced public service announcements that have appeared in English and Spanish in more

than 90,000 separate issues of approximately 11,000 newspapers and periodicals. Separate public service

announcements have been distributed to local television stations around the country.

As described during the Summit by then-Assistant Labor Secretary Olena Berg, the project’s signature

brochure, Top 10 Ways to Beat the Clock and Save for Retirement, presents a basic, easy-to-follow list of

steps individuals should take to ensure their financial security. Steps include determining how much money

one will need in retirement, how to find out what one’s Social Security benefits are likely to be, and how to

find out what retirement savings options are available through one’s employers.

“Most importantly in this brochure, we directed people to other sources of information,” Berg said. The

brochure is available in English and Spanish.

To reach women, the Labor Department worked with organizations such as the Women’s Pension Consor-

tium and the National Council of Negro Women to produce a checklist that encourages women to find

answers to questions particular to their needs. Again, said Berg, the questions are basic ones: “Does your

employer offer a pension plan? What kind of plan is it? What happens to your benefit if you change jobs?

What happens to your benefit if you retire early? What entitlement might you have to your spouse’s pen-

sion or survivor benefits?”

8

9

In its public service announcements, Berg said, the Department wants “our message to cross gender lines,

income and cultural lines so, that all American workers can identify with this retirement savings message.”

One advertisement features Oseola McCarty, who washed clothes for 75 years and never earned more than

$10 a bundle for the laundry, yet managed to save $250,000. Another shows Girl Scouts in Nashville who

are starting their own investment club, in the process demonstrating that it is never too early to start

saving.

Besides encouraging people to get into the pension system, the Labor Department program seeks to make

people already in the system feel secure about their benefits. To that end, it has produced a variety of

materials on protecting one’s pension and knowing pension rights, such as What You Should Know About

Your Pension Rights and Protect Your Pension.

For small business owners, the Labor Department in conjunction with the Treasury Department have

produced a booklet explaining options such as SIMPLE (Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees)

plans, SEP (Simplified Employee Plans), 401(k) plans, profit-sharing plans and payroll-deduction individual

retirement accounts (IRAs). The Department partnered with the National Association of Women Business

Owners to distribute its small business materials to their more than 9,000 members, who are primarily

small business owners. The week of the Summit, the Department also unveiled on its website

(www.dol.pwba.gov) an interactive “small business retirement savings advisor” that will help employers

determine which type of plan is most appropriate for them—and then help them set in motion the process

of establishing a plan for their employees.

“We are trying to help American workers wade through what seems to them like a sea of information,” Berg

said. “We are trying to turn that sea into a pond to make it more accessible.”

Oregon: A Model State Initiative

Jim Hill, the State Treasurer in Oregon, believes it will take all levels of government to address the retire-

ment savings problem—and the levels of government that are closest to the people can be especially effec-

tive in getting information about the issue to the public.

Hill helped persuade the Oregon State Legislature to establish a task force on retirement, which subse-

quently found that less than half of Oregonians were saving through employer-sponsored pension plans,

that the state ranked fourth in the nation in nonmortgage consumer debt, that last year it hit an all-time

high in bankruptcies and, as in the rest of the nation, most people did not know how much money they

have or how much money they will need for retirement.

To help correct the problem, Hill subsequently formed a partnership with public- and private-sector part-

ners to organize Project Green Purse: Everywoman’s Money Conference. The conference, to be held in

September, is expected to attract about 1,300 women to the Portland Convention Center and perhaps a

thousand more to live satellite sites all around Oregon to address the particular retirement issues faced by

women.

“This conference is not just about talk,” Hill told Summit delegates. He said the conference will bring

nationally recognized experts to address substantive issues.

The conference will not be a one-time event. Hill also is working toward holding a conference or series of

conferences to develop a small business pension education agenda. He has drafted an Oregon Savers Act to

10

give permanent focus and resources to the savings issue. And he is seeking to add a standard on retirement

to the Oregon Benchmarks, a series of goals by which Oregonians gauge their quality of life. And as next

year’s president of the National Association of State Treasurers, he hopes to spread the idea to other states

around the nation. “In our way of thinking, the retirement issue is really a part of a larger issue of eco-

nomic security for all Oregonians,” Hill said.

“Choose to Save”: A Model Media Campaign

Many delegates to the Summit argued that the media should play a major role in conveying to the public

that it is important to save for retirement and in helping people get the tools they need to accomplish that

task. The speakers cited as a model for such public education a six-month information campaign conducted

in Washington, DC, developed by the ASEC and the EBRI, and undertaken in partnership with WJLA-ABC

7 television, News Channel 8 and radio stations of the Bonneville Corporation: WTOP, WGMS, Z104.

Associated Press Radio and the

Washington, DC Metro Area Transit Authority joined in the partnership as well.

ASEC and EBRI provided their expertise on retirement issues to help WJLA, the local ABC affiliate in

Washington, produce a series of public service announcements, weekly news segments, community forums

and town hall meetings. The project culminated with a one-hour, prime-time special aired in June. The

entire effort was underwritten by Fidelity Investments.

Contrary to the belief of at least some journalists, the public is very interested in learning about retirement

issues, argued Horace Holmes, a WJLA reporter and anchor. “What I have learned over the past six months

is that the public is extremely interested in personal finance, and that local television newscasts do a very

bad job of giving them all the air time and the type of stories and the type of information that they want,”

he told delegates. All of the viewers that I’ve talked to over the past six months have said the same thing: `I

want to save for my future but, with all of my responsibilities, I don’t know how. I don’t know where to

begin and, even if I did come up with a plan to put some cash aside, I don’t know the best place to put that

money in order to make it grow and work for me.’”

The “Choose to Save” Campaign produced a number of resources that will be available to television and

radio stations in other cities. For instance, it designed specific public service advertisements geared to each

of the three major personality types that experts say characterize those who are failing to save for retire-

ment—“strugglers,” who want to save but are having trouble making ends meet; “impulsives,” who spend

for immediate gratification rather than considering their long-term needs; and “deniers,” who flatly refuse

to face the reality that someday they will reach retirement age.

To help people get started in planning for retirement, the campaign highlighted the “Ballpark Estimate,” a

one-page form developed by ASEC that enables individuals to make quick and easy estimates of what they

will need to save and invest each year to meet their retirement objectives. News stories and other features

of the campaign delved into retirement issues in more depth.

“Whenever we’ve been able during this campaign to inform our viewers about just how simple it is to

formulate that retirement plan, and when we’ve been able to get them hooked up with organizations like

ASEC and EBRI to help them out, the response from the public has been nothing but positive,” Holmes

added.

11

Private-Sector Support

The Choose to Save Campaign owes much of its success to generous financial support from Fidelity, which

allowed for the production of high-quality public service announcements that could be aired during prime

viewing hours. Robert L. Reynolds, president, chief executive officer and managing director for institutional

investment at Fidelity, said the decision to sponsor Choose to Save was an easy one for the mutual fund

company.

“It fit with everything we thought education should be,” Reynolds said. “It was an outreach program, it had

a very strong television presence and, I think, above all, it was a campaign on the basics. If you can take

that type of message into people’s homes, you can make tremendous strides in educating people about

savings.”

Of all the advantages of employment-based retirement savings plans—the opportunity to make tax-deferred

investments, payroll deductions, loan options, even the availability of employer matches—education is the

single most important key to success, according to Reynolds.

He should know. Fidelity works with more than 5,000 corporations, handling 401(k) plans for more than

five million participants. Educational efforts are starting to pay off in a dramatic way, he says: the average

balance in the 401(k) plans managed by Fidelity is over $50,000. Fully 85% of eligible employees participate

in the plans. And the average participant is putting 75% of his or her funds in equities—a “very, very

healthy asset mix” that reflects a good understanding of what type of investment is likely to produce the

best returns over the long run.

Reynolds said efforts like WJLA’s should be replicated around the country, and he noted that exciting new

ways of getting the word about retirement savings out to the public are emerging. He said the Internet, in

particular, offers a promising new avenue for educating people about retirement saving and investing

because “it puts real-time information in front of people, and allows you to put material out that is

customized to the individual user.”

All this demonstrates, Reynolds concluded, that “public education is a process and not a one-time event.”

Employers, Retirement Plans and Education

Nobody is in a better position to help employees come to grips with the financial issues surrounding retire-

ment than employers, who have the opportunity to sponsor tax-advantaged retirement plans, the access to

employees to explain retirement issues and, importantly, the chance to build trust needed to make the

message about retirement savings take hold.

But getting that message across takes effort. Summit delegates lauded Hard Rock Cafes, a RankAmerica

unit, for demonstrating how employers can communicate effectively with their workers about retirement—

even to a population of employees that is relatively disinclined to consider retirement issues because it is

young and receives relatively low income.

Hard Rock offers employees who invest the minimum 2% of pay in the company’s 401(k) plan an employer

contribution equal to another 3%. Employees can defer as much as 19% of their pay. In addition, they can

invest in any of seven different mutual funds, can transfer funds between accounts daily, and can change

the amount they are deferring every quarter.

12

Despite the appeal of such a plan, the level of employee participation was disappointing at first, says

Anthony R. Amato, director of compensation and benefits for the company. But that changed after the

company adopted a new education program geared to its own employees, who tend to be young and rely on

tips for a substantial portion of their income.

“Think of it as a 150% tip,” the company said on a new brochure that explains the details of the plan and

such arcane topics as compounded interest, vesting rules and loan features, all in a breezy tone. “For those

of you who haven’t gotten it yet, THIS IS FREE MONEY,” the brochure adds, returning to the issue of the

employer match.

The award-winning brochure, developed and produced by Hard Rock’s own graphics and design group with

help from Buck Consultants in Atlanta, incorporates other aspects of Hard Rock’s corporate culture. But

Amato says companies cannot rely solely on paper brochures to convey the message about retirement.

That’s partly because of the cost: the company last year shipped six tons of paper explaining its retirement

program to employees. But it also is a question of effectiveness.

“We need to leverage technology and create a self-service environment for employees,” Amato said. “What

we are hoping to do is get into an all-access, 24-hour, seven-day-a-week kiosk where employees can have

access to all the information they normally would get through printed material. And it would include

interactive videos and games and things of that nature, located in the restaurants.”

Important as such efforts are, employers cannot do the job of educating workers alone, according to Amato.

He emphasized the importance of teaching children at an early age—in elementary schools—to learn

attitudes likely to help employment-based retirement plans take root.

“We should be targeting elementary schools and our children and talking to them about saving and getting

that message across,” Amato said. “It is important for them to come up into the ranks of the Hard Rock, if

you will, already with the notion `I can save, I know how to save and take advantage of the programs that

employers offer.’”

IV. Break-Out Facilitators Reports: Barriers and Opportunities

Much of the hard work of the Summit was done by delegates participating in nine break-out sessions. Over

the two days of the Summit, delegates met twice in small groups to identify barriers that stand in the way

of increased retirement saving and to brainstorm about various opportunities for overcoming them.

The goal of the Summit was not to reach consensus; time was too short for that. Nevertheless, a number of

themes arose repeatedly: the need for individuals to make an increased personal commitment to savings;

the need for a strong commitment from employers to help employees build future retirement security; the

need for government policies that are clear, simple, consistent, flexible and stable; the need to provide

appropriate incentives and reduce costs to plan sponsors, while at the same time protecting workers; and

the need to raise the profile of retirement savings in the minds of the American public.

Significantly, numerous delegates suggested that the ultimate solution to America’s retirement savings

challenge lies in fundamental cultural change, in finding ways to put more value on saving and less on

consuming. They consistently said such change will require the participation of institutions and individuals

from every sector and every walk of life. And, they repeatedly returned to the theme that education—

whether by schools, employers, government, the media or others—will be the crucial element in any suc-

cessful strategy to increase retirement saving.

Summaries of the break-out group deliberations, which stretched over both days of the Summit, follow.

They were compiled from presentations prepared by group facilitators and note-takers. A more detailed list

of the ideas produced in those sessions can be found in Appendix 3 of this report.

These ideas were suggested by individual Summit participants. They do not represent a consensus. They

were not prioritized.

A. “Dark Blue” Group

This group was characterized by an extraordinary diversity in views on both barriers to retirement saving

and opportunities to ameliorate the problem. Moreover, the suggestions ran the entire spectrum from

generic themes to unique items.

Delegates identified several major barriers to retirement savings, including consumerism among

Americans—especially young people, who have no real understanding of delayed gratification. Most

Americans have no heritage, or culture, of saving, members said. This is partly because many people do not

understand financial issues or existing retirement saving programs and opportunities, a problem that

arises at least in part from the lack of attention the media pay to this issue.

In general, the group said that no one is taking the lead to start a massive, national campaign to whip up

enthusiasm for saving for retirement. In particular, no one is reaching small employers with persuasive

reasons to start retirement plans.

The group noted, however, that there probably are no easy answers for marginal workers, women and

minorities.

The group seemed united in believing there are very real opportunities to simplify existing rules and

13

regulations and to create partnerships involving government, business and educational institutions in the

effort to reach the younger generation and teach savings behavior instead of consumption. Moreover, it said

opportunities exist to expand the public’s knowledge of economic security issues in general.

Barriers for Individuals and Employers

The group identified three categories of barriers to increased retirement savings: current laws, economic

realties and lack of understanding among employers and employees.

Concerning the current legal environment, group members said the tax code penalizes saving outside of

qualified retirement plans. The group discussed several suggestions for creating tax incentives for saving

and for taxing consumption rather than saving.

The group also discussed whether certain retirement plans, particularly defined contribution plans, may be

too easily accessible before retirement. It explored the idea of modifying cash-out rules. It also considered

the possibility of requiring a “cooling off period” during which job changers could not spend funds received

as lump-sum distributions.

Delegates in the group also suggested that lack of portability is a barrier for many employees. This was

discussed in the context of both defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans. The group discussed

what some described as rather arbitrary constraints on transferring funds between defined contribution

plans that originate under different sections of the Internal Revenue Code.

The group cited a number of economic “realities” that it says militate against retirement saving:

• It is hard for working people to save.

• Individuals and employers often take a short-term view, focusing on more immediate concerns than

retirement.

• Part-time and older workers, as well as cyclical workers, often lack access to retirement plans.

• Women face special complications arising from periodic interruptions in their careers to raise children

and due to divorce.

• Post-retirement health issues often are not addressed in retirement planning.

The need for more education occurs among employers and employees and involves all savings and financial

issues, the group said. It also suggested that the “savings industry” often neglects non-English speaking

populations.

The group identified specific types of education needs:

• How much saving is needed for retirement.

• We need a broader definition of “security.”

• Employers need a better understanding of existing retirement programs, such as SIMPLE and SEP

plans.

• Employees need to be more aware of the bargaining power they have during times of high employment.

They can demand more coverage with respect to employer-sponsored retirement plans.

• People need help in understanding the impact of inflation. Reporting accumulated balances in nominal

terms may mislead some employees.

• The media need to be educated on how to report financial issues.

14

Opportunities

The group identified a number of opportunities for the private and public sectors to encourage retirement

saving either unilaterally or in partnership with each other.

Private-sector opportunities include:

• Education projects.

• Payroll deductions and direct deposit for IRA investments.

• Invite workers’ spouses to attend retirement planning seminars for employees.

• Educate people on the costs of retirement.

• Use regular statements for investors as a tool to educate.

• Consultants and service providers may need to push employers to cover rank and file workers.

• Offer stock options.

• Remove barriers to portability.

Possible public-sector initiatives include:

• Education projects that start at a young age.

• Create stronger public demand.

• A national campaign tailored after the “Buy War Bonds” effort.

• Try to decrease consumerism.

• Create tax incentives, or perhaps eliminate taxes on savings.

• The government should conduct a survey or analysis of existing trends in defined benefit and defined

contribution plans.

• Stimulate new saving rather than the transfer of existing assets.

The group agreed that collaborative efforts would be useful. Some examples of these include:

• Link employers with someone else to increase trust among employees.

• Develop curriculum, public service announcements and media advertisements.

• Develop financial planning curriculum for high schools and colleges.

• Groups like the Chamber of Commerce and various labor unions should promote pension concepts to

their members.

• Encourage voluntary but automatic enrollment and contributions in retirement plans.

B. “Gold” Group

During the break-out sessions, the Gold Group exchanged many ideas. While it was unable to reach

consensus on all issues, there was widespread agreement on many issues.

Barriers

The group began by identifying barriers that prevent individuals and employers from saving for retirement.

One of the first barriers it identified is that for many Americans, earnings and benefits are just too low.

Many individuals are struggling to make ends meet, and are unable to really focus on retirement savings.

The high level of taxes only exacerbates their low level of earning.

Still, the group said that individuals must take more responsibility to save for their own retirement. People

could increase retirement savings by making simple choices. They can choose to pay off their credit card

balances, which carry high finance charges. And they can choose to take advantage of savings vehicles such

as 401(k)s, or to invest more in these accounts.

15

There is a strong need for education among Americans. Many people do not enter the workforce with good

savings habits; they tend to focus too much on their immediate needs. Americans live in a consumption-

oriented society. We are taught to gratify current needs rather than to save for the future. Credit cards are

easy to obtain, and the number of individuals declaring bankruptcy is at an all time high. Saving money for

the future is rarely discussed in newspaper articles, in sitcoms, or other prime-time television shows. In

addition, not enough government programs encourage savings.

Because saving for their retirement is not a high priority for individuals, companies have been discouraged

from expanding retirement savings programs. Individuals would prefer higher salaries to other employee

benefits.

Another barrier to employers is that retirement plan options are often complex, administratively burden-

some and often expensive to adopt. High start-up costs make it especially difficult for small businesses to

set up retirement plans. Even when employers would like to offer plans, many do not feel confident that

they have enough information. This lack of information occurs both because the private sector does not

adequately promote employer plans and because it is considered a social taboo for employers to discuss

retirement and financial status.

Opportunities

Many policies could encourage savings. We need to educate both employers and employees. The govern-

ment, employers and the private sector should be encouraged to work together to provide education.

One way to reach a large number of individuals is through the mass media. People would be interested in

receiving this information if it were available to them, but few newspaper and magazine articles—and even

fewer television shows—discuss retirement savings. We need prime-time informational television shows on

retirement issues. Even sitcoms could use retirement themes to raise public awareness. More newspapers

and magazines could run features on the importance of saving and on how to go about doing so.

Government policies also should be changed to encourage people to save. High taxes prevent many indi-

viduals from saving; tax cuts would allow more people to save. IRAs could be expanded to allow people to

invest more money, and tax breaks could be given to help businesses—especially small businesses—meet

start-up and administrative costs.

Once people have begun to save money for their retirement, they should be encouraged to leave that money

set aside. There should be stronger penalties for people who withdraw their money early from retirement

accounts, and the government should pass pending legislation that allows more portability between retire-

ment plans.

Employers can do more to educate the workforce and encourage employees to save. Companies should begin

or expand retirement programs, encourage payroll deductions and offer matching contributions. In addi-

tion, earlier vesting would help many individuals—in particular, women and minorities. Automatic enroll-

ment in 401(k)s also would help; employers who have tried this have seen the number of people enrolled in

their 401(k) increase dramatically. [During the Summit, President Clinton sought to clarify that employers

currently have the authority to enroll employees automatically. Under this approach, employees would

automatically become participants in a company-sponsored retirement plan unless they opt out.]

16

When companies give their employees pay increases, they should encourage them to invest that money.

While many barriers prevent people from saving, the Gold Group felt these barriers can be overcome once

people realize the importance of savings and once savings opportunities become more readily available.

Retirement savings, in short, can increase with the help of the government, employers, the private sector

and individuals. But the chances for success will be greatest if all of these groups do their part to encourage

increased saving.

C. “Green” Group

The green group’s discussions were positive, productive and focused. Numerous ideas were articulated.

While the perspectives of the delegates differed, there was general agreement from the delegates on most, if

not all, of the issues reported here. However, the group arrived at opposing opinions on a very small num-

ber of issues.

Individual Barriers

The group identified a number of barriers that prevent individuals from saving for retirement.

The group said that personal beliefs, motivation, attitudes and fears play an important role as barriers. In

addition, the group suggested that many Americans don’t recognize that retirement savings is a problem,

and do not consider it a priority. Also people do not have a savings ethic, and do not believe they will live

long enough to enjoy the benefits of retirement.

In addition, the group noted that many individuals believe that setting aside small amounts won’t make a

difference, so they see little reason to save. And, if individuals are motivated to save, it is often for shorter

term goals, such as cars.

According to the group, Americans are influenced by a consumer economy that promotes buying rather

than saving, an attitude the media does nothing to discourage. This is demonstrated by the free spending

patterns of many individuals using widely distributed, easily accessible credit cards. The spend-now

attitude causes individuals who change jobs to withdraw funds from their retirement savings and spend it,

rather than roll it over to other savings vehicles. Moreover, individuals have many fears about saving,

including having math phobia when it comes to money and financial calculations.

Efforts by investment companies to scare people into action by telling them how much they need to save

actually can scare individuals into inaction by giving them a sense of helplessness according to the group.

Lack of knowledge on savings hinders many people from saving. They do not have a clear understanding of

how to invest or how much to invest; who to turn to when making investment decisions; what investment

vehicles are best, safe and correct for their individual situation; where to begin saving and how to set

priorities; and why saving for retirement is important, the green group noted.

Generally, primary and secondary schools haven’t adopted financial management curricula that include

these types of topics. Typically, teachers are not trained to instruct students in managing money and in

financial issues, and parents in many cases are not able to teach their children about these topics. Further-

more, financial institutions do not educate the public in money management and savings. As a result,

people do not understand the value of savings or such issues as the power of compound interest.

17

For those who do understand the basics of saving and its importance, the investment process is still com-

plex. There are too many investment tools, forms and decisions to make. Individuals do not know where to

begin. The complexity of the investment process makes people fearful to invest, since they see investing as

a large risk.

Members of the green group discussed whether insufficient income is truly a barrier to saving. While there

was some debate, they agreed that low income is a particular concern for women, minorities and younger

Americans. Some delegates suggested that income taxes and Social Security taxes are too high, but others

disagreed. In addition, some members said tax breaks for investment are too limited, some noted that many

people are having difficulty living “day to day,” and some said college graduates often are too burdened with

school loans to start saving.

Rules governing many savings vehicles are not “saver friendly.” Some rules are too complex to understand,

while others limit what individuals can contribute. Savings vehicles such as IRAs do not allow individuals

to make catch-up contributions to compensate for periods when they could not save because they were sick

or out of the labor force. Also, many banks require a fairly substantial minimum balance before interest

accrues. And it is too easy to withdraw retirement funds early, defeating the purpose of saving for

retirement, according to the green group.

Employer Barriers

The group suggested that rules and regulations on establishing and maintaining pension plans prevent

many employers from sponsoring retirement plans. In particular, complex rules and cumbersome reporting

requirements “scare off” small companies. The penalties for making mistakes are very large, and all compa-

nies fear the potential liability from lawsuits for plans that do not perform as well as participants hope.

The rules for defined benefit plans are considered especially onerous, the group said. Further complicating

the situation is the fact that different rules apply to different types of employees and types of employers.

Because of the difficulty of combining different types of plans, mergers can lead companies to terminate

plans instead of continuing them. Contradictory rules also limit portability of retirement savings when

employees changes jobs.

Complexity of rules makes the cost of complying high. Large employers can overcome this problem because

they have many resources, but smaller employers typically have much more limited resources.

Employers typically find that employees value health benefits over pension benefits, so employers respond

accordingly. The high cost of health care has forced some companies to choose between offering health care

and providing retirement plans. Retirement often goes by the wayside. Furthermore, continual changes in

pension and tax rules make it costly and time-consuming for companies to keep their pension plans quali-

fied. In addition, many employers lack knowledge about setting up plans, administering plans and promot-

ing employee education on retirement savings. These activities typically are perceived as costly and diffi-

cult.

Opportunities

The group had many suggestions for opportunities to encourage savings. They fall into several general

themes: simplify, clarify, measure, communicate, collaborate, educate and induce.

18

In order to simplify and clarify rules on savings, the group suggested that the President and the Congress

should create a national policy on retirement savings. The policy goals would be to: 1) simplify laws and

regulations while retaining protections intended by the laws and regulations; 2) look at laws and rules that

adversely affect all Americans, particularly low-income groups, and eliminate or revise them; 3) if neces-

sary, develop new laws and rules that help Americans, particularly low-income groups, save more, and 4)

identify conflicts in the laws and regulations between agencies such as the Pension Benefit Guaranty

Corporation, the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Labor and the Securities and Exchange

Commission, and revise them to make them more compatible.

The group suggested using data from materials prepared for the Summit on patterns and trends for the

overall state of retirement saving, and for various groups, as a baseline against which future progress could

be measured. By the 2001 Summit, these data could be compared with actual outcomes.

A national marketing campaign would help promote retirement saving. It should use different strategies to

reach different demographic groups. It should develop a recognizable symbol to promote public awareness

of the importance of retirement savings. The campaign should include a strong partnership with the media,

which should provide time and space to the effort as well as report positively on the retirement savings

issue. Creation of a network among those concerned with public education and retirement savings issues

also would help. The American Savings Education Council (ASEC) can and is serving as a clearinghouse for

materials on retirement saving and parties involved in the issue. ASEC can and will expand its role to keep

Summit participants informed about employer and community service “best practices” in savings education.

A comprehensive education strategy on the importance of personal finances, money management and

saving for retirement is needed. This strategy would cover elementary and middle schools, and provide a

curriculum on managing money and personal finance, with training to help teachers learn this curriculum.

High school students should be required to take and pass a course in financial management in order to

graduate.

Since education is a lifetime process, universities should develop courses on savings for college students and

the community in general. Employers also could develop programs to educate employees on saving and

financial planning, and larger employers could mentor small employers by providing expertise and by

sharing savings educational information materials.

Governors should be enlisted to promote statewide retirement education strategies. Perhaps there should

be a competition between the states to see which can achieve the highest percentage of its population that

saves for retirement. In addition, social service agencies could create savings education programs to go

along with counseling programs and job training, and they could target low-savings groups such as women

and low-income individuals in this effort.

Tax incentives should be created to encourage savings at the individual level and make pension plans more

attractive to individuals and employers. The tax structure needs to be reviewed and changes made that

would eliminate complexity and make it easier and less costly for employers to offer pension plans. In

addition, small companies can form associations to offer larger group pension plans with reduced adminis-

trative costs for each individual company. In this effort, pension plans could be made more portable, and

therefore, more attractive to individuals.

19

D. “Light Blue” Group

The light blue group was very diverse, and offered a great diversity of opinions and options for consider-

ation. No attempt was made to reach consensus on barriers or opportunities. Rather, everyone in the group

had a chance to share their thoughts and ideas—some of which were similar or related, and some of which

were very different. What follows is a summary of the thoughts and ideas expressed.

Individual Barriers

The light blue group recognized that there are serious barriers keeping individuals from saving adequately

for retirement. These include, but are not restricted to, a lack of knowledge and skill about managing

income, spending money, planning for retirement, saving, taxation and thrift. These are issues in all com-

munities throughout America, but can be especially challenging for women and minorities.

More generally, society tends to be focused on consumption rather than on the virtue of thrift.

It was argued that the current tax structure discourages savings and encourages consumer spending. High

taxes also make it difficult for people to save. In addition, many individuals, especially women and minori-

ties, lack disposable income. There is an absence of a societal commitment to high-wage jobs that would

make savings more feasible for various segments of our society.

It also was noted that the increasing costs of higher education can impair one’s ability to save for retire-

ment. And it was suggested that attacks on affirmative action can reduce educational achievement and

ultimately limit economic success and security.

Employer Barriers

Several barriers reduce the ability of employers, especially small businesses, to offer retirement plans.

Complex regulations and compliance standards, as well as the existence of potential penalties, often deter

businesses from offering certain retirement programs. Employers who offer retirement plans sometimes

worry about confusion that may arise when they attempt to educate employees, and they fear their educa-

tional efforts could be perceived as giving advice, in which case they might be judged to have assumed

fiduciary responsibility.

The group also cited high labor force turnover and the resulting lack of mutual commitment between

employers and employees as barriers to retirement saving. It said there is an apparent lack of employee

interest in retirement benefits. While some members suggested that greater demand for such benefits from

employees would motivate employers to offer plans, others noted that turnover sometimes contributes to

that lack of employee demand.

Lack of employee demand often combines with lack of resources to prevent small employers from offering

retirement plans.

The group also suggested that lack of mutual trust between employees and employers sometimes leads

workers to question whether promised benefits will be there when they retire. But some also suggested that

employers are shifting the burden of retirement savings and the risks associated with investing retirement

funds to employees by offering defined contribution plans instead of defined benefit plans.

20

Members also mentioned a lack of education among employers, saying employers need more information so

that they can choose the type of plan that is most appropriate for them.

Barriers to Increasing Public Awareness

The No. 1 barrier to increasing public awareness seems to be the need to compete with a consumer-oriented

society. An ethic of thrift and saving is missing in many segments of our society. Advertising campaigns are

needed, including ones directed at lower earners, to create this ethic along with a sense of urgency about

saving. The public also needs help figuring out how—and how much—to save for retirement. We should do

a better job of teaching thrift and saving to children.

It also was noted that there is a lack of a moral outrage at a public policy that sponsors lotteries that appeal

to the most vulnerable members of our society. Some argued that financial institutions should do more to

increase public awareness, especially among minorities and women, who represent an untapped market for

such companies. But, group members said, there seems to be a lack of market incentives to get financial

institutions to go after this market. At the same time, some segments of society lack trust in financial

institutions.

The view also was expressed that, with an increasingly diverse workforce, we may be expecting too much

from employers.

Opportunities

We should undertake a national campaign (including, but not restricted to, public service announcements)

to make savings a high priority for individuals and give them the knowledge and tools to act. Individuals

should be encouraged to assume responsibility, and they should be educated on strategies for managing

their financial resources. Better government communications are needed, especially for non-English speak-

ing people.

Both government and business should be models of thrift and concern to the public; and they should en-

courage an attitude of thrift and savings among their employees and the general public. Government

should lead by example in its treatment of public-sector employees. Employers should raise the profile of

the plans that are already available to employees, and provide ongoing education. Among other things, they

can try to encourage participation in retirement plans by workers when they receive raises.

We should continue to simplify pension plans, and continue to generate new types of plans. The public

needs to examine the implications of the growth in defined contribution plans and consider policies to

promote defined benefit plans (including simplified defined benefit plans for small businesses). We should

consider expanding the availability of multiemployer pension plans.

More focus should be given to lower-income groups. The financial community should become more involved

with and focused on lower-income areas. Part-time workers should be given access to pension and other

retirement programs. We should identify and provide incentives to encourage saving among low-income

wage earners. Another possibility is to raise the minimum wage to allow more opportunity for saving.

Congress should debate changes to the tax code designed to promote savings, including whether to funda-

mentally restructure the tax code. It should allow catch-up provisions that allow individuals to save more at

later ages, when they are better able to save.

21

But we should not put all the burden on either the public or private sectors. Individuals and communities

must get involved, and government and employers should work together.

E. “Orange” Group

The orange group generated about 200 thoughts and comments. It had, for a moment, the idea we might

come to consensus on some of those but decided, instead, to try to cluster them in three major areas:

• First, that as a result of this Summit, Americans should make adequate retirement income a clear

national priority.

• Second, that simplification of government policies and provision for increased incentives to save must

also be a nationwide priority.

• Third, that education is likely to be the key and that it must occur throughout the life span and in all

types of environments.

Making Adequate Retirement Income a National Priority

Unequal access to savings opportunities is one of the biggest barriers to making adequate retirement

income a national priority. Tremendous, conflicting demands are placed on the part of families these days.

It becomes very difficult to make savings the No. 1 priority if that means forsaking putting food on the

table.

There is a great deal of misinformation in the country about the necessity and availability of retirement

systems for a large percentage of our population. The advertising marketplace emphasizes consumerism to

the extent that savings is not a high priority.

The group suggested five or six specific opportunities to make adequate retirement income a national

priority.

Members said it is critical to create standards and mechanisms that make it possible to provide adequate

retirement income for every single American. We should allow for direct deposit and payroll deductions into

retirement accounts. People should be able to save in a variety of locations and ways, whether in grocery

stories or perhaps through a surcharge on Lotto tickets. There should be catch-up provisions for individuals

who need to make up for missed savings opportunities earlier in life. And we absolutely must maintain

some minimal level of support for all of our citizens.

Simplifying Government Policies and Creating Savings Incentives

Concerning the simplification of government policies and the provision for increased incentives to save,

there are four or five types of barriers.

Confusion over the security of savings tends to be a large fear factor for many Americans. We need much

more information about how that system operates and the degree to which people can have confidence that

it will continue to operate.

Lack of portability is another barrier, as are restrictive regulations placed on businesses and individuals.

Orange group members suggested that it is critical to reduce the number of government mandates and give

employers and employees more freedom to choose programs that cover all levels of earners.

22

Vesting periods should be shortened, and taxes and regulatory burdens on small businesses should be

examined.

Business and government must continue to maintain effective partnerships. We must find more ways to

encourage multiemployer types of retirement plans. We must encourage more private-sector contributions

to the education of individuals.

We should explore the idea of taxing consumption and not savings. We should advance legislation to in-

crease portability of retirement savings. And we should support opportunities to roll over retirement invest-

ments.

Lifetime Education

Barriers to education certainly include the lack of quality and accurate information available to a variety of

individuals. There are many misperceptions and misunderstandings about the nomenclature used by

retirement professionals.

There is a lack of educational opportunities and content. We need to start educating people about retire-

ment issues and finance earlier. We must find ways to teach and understand the complexities of savings

and such issues as compound interest.

We must find ways to capitalize on the advent of new media and communications skills. Members talked

about placing kiosks in malls where the kids are walking around, finding ways to use e-mail, and capitaliz-

ing on the entertainment world: maybe we need Oprah to help us, or perhaps we need to think about

enlisting sports stars to speak out about retirement issues.

School partnerships, earlier education and education throughout the life span will be critical as we help

individuals understand the risks they must consider—risks that include changes in life expectancy, unan-

ticipated changes in personal lives, or the possibility that one will be come disabled or suffer health prob-

lems later in life.

F. “Purple” Group

The group met twice to discuss a series of questions concerning barriers and opportunities for individuals

and employers. It held a third meeting to summarize the prior meetings and decide what would be pre-

sented to the delegates of the Summit.

The first session focused on barriers, and addressed three questions: 1) What are the barriers individuals

face in saving for retirement?, 2) What are the barriers employers face in providing opportunities to help

their employees prepare for retirement?, and 3) What are the barriers to increasing public awareness of the

value of saving for retirement?

The second session dealt with opportunities for both individuals and employers. It specifically focused on

two questions: 1) What can the private sector and other non-governmental organizations do to address the