Brown Bag Lessons

e Magic of Bullet Writing

By

E R. J

Chief Master Sergeant, USAF, Retired

Edited by

D A

Master Chief, USN, Retired

Air University Press

C

urtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education

Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

Project Editor

Belinda Bazinet

Copy Editor

Tammi Dacus

Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations

L. Susan Fair

Composition and Prepress Production

Vivian D. O’Neal

Print Preparation and Distribution

Diane Clark

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jaren, Eric R., 1964- author. | Air University

(U.S.). Press, publisher.

Title: Brown bag lessons : the magic of bullet

writing / Eric R. Jaren.

Other titles: Magic of Bullet Writing

Description: First edition. | Maxwell Air Force Base,

Alabama : Air University Press, [2018]

Identiers: LCCN 2017052719| ISBN

9781585662784 | ISBN 158566278X

Subjects: LCSH: United States—Armed Forces—

Promotions—Evaluation. | United States—Armed

Forces—Promotions. | Employees—Rating of—

United States. | Performance awards—United States.

Classication: LCC UB323 .J37 2018 | DDC

808.06/6355—dc23 | SUDOC D 301.26/6:B 87

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052719

Published by Air University Press in December 2017

Copyright © 2012 by Eric R. Jaren

Disclaimer

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed

or implied within are solely those of the authors and do

not necessarily represent the ocial policy or position of

the organizations with which they are associated or the

views of the Air University Press, Air University, United

States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any other US

government agency. is publication is cleared for public

release and unlimited distribution.

AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS

Director and Publisher

Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell

Air University Press

600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405

Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010

http://www.au.af.mil/au/aupress/

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress

and

Twitter: https://twitter.com/aupress

Air University Press

iii

Contents

List of Illustrations v

Foreword vii

About the Author ix

Acknowledgments xi

Preface xiii

Introduction xv

Part 1 Timeless Lessons

1 Genesis 3

2 A Better Mousetrap 7

3 A Consistent Approach 11

Part 2 e Magic

4 Bullet Formats 17

5 Performance Levels 29

6 e Performance Scale 39

Part 3 Practice Makes Perfect

7 Scoring Mechanics

53

8 Top 10 Writing Traps 59

9 Perfect Practice Makes Perfect 67

Part 4 Conducting Boards

10 You Just Can’t Make is Up

105

Abbreviations 109

Appendix 111

v

List of Illustrations

Figure

1 Tactical-Operational-Strategic 21

2 Tactical-Tactical-Tactical 21

3 Tactical-Tactical-Operational 22

4 Tactical-Tactical-Strategic 22

5 Performance-level model 31

Table

1 Performance-level scores 54

vii

Foreword

What leader in any organization hasn’t sat back and internally

screamed, “ere has to be a better way!” Reader beware, there is a

better way. What I inherently knew as a member of US Navy E-7

through E-9 selection boards, CMSgt Eric R. Jaren has captured in a

systematic process useful for every level of leadership. e consis-

tency in the approach embodies reective, thoughtful consideration

to capture the truth and proper context of every person’s accomplish-

ments. e use of performance levels is not conned to any specic

military service. Indeed, it’s universal in application in any business

and culture. e addition of this model into company grade ocer

(CGO) and senior noncommissioned ocer (SNCO) combined cur-

riculum underpins the operational and long-term strategic impor-

tance for the force.

is model was implemented into the Senior Noncommissioned

Ocer Academy (SNCOA) and CGO curriculum as a “best practice”

for meeting the responsibility to mentor institutional competencies

directly impacting the careers of the team. Feedback from students,

scholar-warriors, substantiates the model. e model provides un-

adulterated feedback in mentoring and maintains integrity with pro-

motion and award processes. From this, leadership, followership, and

the core doctrine of developing Airmen are assured. No other presen-

tation media in 33 days of curriculum was asked for by more students

to take back for use in operational units.

DON ALEXANDER

Command Master Chief, USN, retired

Director of Curriculum

Air Force SNCOA

ix

About the Author

Aer 30 years of leading our nation’s Airmen, Chief Master Ser-

geant Eric R. Jaren’s powerful fervor to write Brown Bag Lessons, e

Magic of Bullet Writing is a reection of his passion for developing,

coaching, and mentoring all Airmen. Chief Jaren literally inuenced

the lives of thousands through his seminars and motivational talks

about taking care of Airmen and their families and how to communi-

cate their accomplishments through the written word. With the

Chief, it always comes back around to the core focus of developing

leaders. e magic of this masterpiece is that these timeless brown

bag lessons can be used by any organization—both military and civil-

ian. Chief Jaren’s personal mantra has always been “Find a Need,

Meet a Need,” and his desire for you is that the struggle to write comes

to an end. Are you ready for the magic?

Chief Jaren retired from the US Air Force in 2012. Formerly the

Command Chief Master Sergeant for Air Force Materiel Command’s

13,000+ enlisted Airmen and their families, Chief Jaren’s30-year ca-

reer brought him from the ight line as an aircra mechanic to the

front line as a senior Air Force leader. He’s a warrior Airman who’s

deployed worldwide, including support of Operations Desert Storm

and Desert Shield, Iraqi Freedom, and Enduring Freedom. Chief

Jaren holds a master’s degree in business administration from Trident

University and an executive certicate in negotiation from the Uni-

versity of Notre Dame.

xi

Acknowledgments

By associating with wise people you will become wise yourself.

—Menander, Greek dramatist

In the year preceding my retirement, friends, peers, and colleagues

asked that I capture these techniques so they wouldn’t be lost with my

departure. So, I put pen to paper in the hope that future generations

won’t have to relearn what is already successful. Between the covers

you’ll nd contributions from people cut from the same cloth. Please

allow me to give credit where credit is due.

anks also to omas Jones and Manuel Sarmiento who oered

critical input used to explain the origins of the concept presented; to

Alexander Perry, Anderson Aupiu, and Christopher Powell—my

peers, mentors, condants, and dear friends—who were proponents

oering feedback to the original principles; and to my dear friends

Andrew Hollis, Casey Schoettmer, and Sean Chaplin. I owe much

gratitude for their eorts as contributing editors and thoughtful sug-

gestions to the substance.

A very special thank you to my “ambassador of quan,” Mark Brej-

cha, for writing the “About the Author” section.

1

I’d also like to ac-

knowledge Robert Stroebel, Dave Gilmore, James Martin, Wesley

Riopel, Alan Braden, Edward Ames, James Shepherd, Michele Owc-

zarski, and Justin Deisch for thoughtful contributions and being in-

credible advocates, proponents, and mentors who invest in their

people; and to Mark Bennett and Don Alexander for taking the prin-

ciples to the Squadron Ocer School (SOS) and SNCOA.

A special thanks to Don for his eorts as a contributing editor,

writing the foreword and accepting the responsibility to prepare this

manuscript for submission to Air University Press. I cannot thank

you enough for your seless eorts.

Warmest regards for all my mentors and teammates.

Note

1. Reference phrase used in the 1996 movie Jerry Maguire with Tom Cruise and

Cuba Gooding Jr. “Jerry, you are the ambassador of quan.” e meaning of quan, in

this instance, meaning to be at one with a particular thing or skill.

xiii

Preface

Start with why.

—Simon Sinek, motivational speaker/author

Brown Bag Lessons, e Magic of Bullet Writing is the rst book in

a series on leadership. is book centers on eective bullet writing

and guarantees immediate improvement. Skillful writing doesn’t

have to be dicult.

No other book approaches writing the way this book does, and no

other book teaches these techniques. Aer reading this book, you

will fully understand how to write bullets and “why” every word

matters.

In 2003 the author created a seminar to teach a fair and consistent

process to evaluate recognition packages. is seminar transformed

an entire organization within six months. Since then, the techniques

have decisively transformed the writing, recognition, and promo-

tions of every organization applying them.

e practices in this book continue to positively impact the Air

Force and sister services through professional military education. In

addition, the concepts have helped transitioning service members

and college students better communicate acquired capabilities and

competencies on their résumés. Read on to discover the “magic” and

open your eyes to a brand new way to look at writing.

Recent changes to the US Air Force enlisted promotion system

make it more important to document your very best accomplish-

ments. Under the new system, points come from the most recent en-

listed performance reports (EPR). e new system requires fewer

lines, so Airmen must communicate the best accomplishments and

not just words that ll the white space. is Magic of Bullet Writing

will ensure you know how to articulate not just what you are doing

but also convey your strongest competencies and capabilities so the

promotion board can fully assess your potential. Training materials

that correspond to the lessons in this book are available for free

download at http://www.brownbaglessons.com.

Are you ready for the magic?

xv

Introduction

e task of leadership is not to put greatness into people, but to

elicit it, for the greatness is there already.

—John Buchan, Scottish novelist, historian, and politician

Developing, coaching, and mentoring are my passion—investing

in others has brought more satisfaction than any individual accom-

plishment. So, it would seem the time and energy spent helping oth-

ers to succeed is returned twofold in contentment. at is what likely

inspired my mentors to make an impact early in my career.

While I don’t consider myself a “writer,” I do consider myself a

coach and mentor—someone who is willing to help others build a

brighter career. I have been presenting professional development

seminars for many years, as a job requirement but also, more impor-

tantly, as a personal passion.

From 2002 to present I shared techniques of military writing in

every forum imaginable. Whether presenting in a base theater, a con-

ference center, or via my laptop in a hotel room in Okinawa, Japan,

developing people is what makes me go.

e genesis of this book’s material was initially shared with small

groups. rough the years, audiences grew from dozens to more than

500 people at a time. During the last few years, the seminars reached

tens of thousands.. Like a light switched on, time and again, people

attending the seminar said, “I get it.”

is system has the potential not only to revolutionize how we ap-

proach bullets but also to transform our entire merit-based system.

In January 2012 the Air Force recognized the force-wide value and

inculcated the concepts into the SNCOA and SOS curricula. Before

being discontinued in 2014, over 28,300 students received this infor-

mation through the course curriculum.

I wholeheartedly recommend the principles outlined in this book.Our educa-

tion institutions incorporated these principles into curriculum for more than

5,000 company grade and senior non-commissioned ocers annually.

ere are three main reasons why each leader should embrace these tech-

niques. First, the writer is forced to ensure each bullet meets a set standard.

Second, it creates consistency and structure within the Air Force. By applying

these sound principles, leaders will assist with the evolution of our perfor-

mance evaluation system, awards boards, and even promotion boards by cre-

ating a systematic approach to bullet writing to remove ambiguity within each

INTRODUCTION

process. And third, these techniques add credibility to our system. Each bullet

will now have merit. erefore, every board member can easily assign a point

value to each bullet and be able to support the overall rating to fellow board

members. No longer will there be an ambiguous guess at how a board member

arrived at their rating. Each time I use these techniques on boards, it helps

identify the most deserving person.

—CMSgt Mark Bennett, USAF, retired

e most distinctive part is that these techniques do not teach

through conventional methods. ese principles teach from the op-

posite point of view, from the evaluation side for clear understanding.

I have observed thousands struggling to compose, articulate, and

formulate statements for recognition packages and performance ap-

praisals. People spent countless hours in frustration because they

were writing in vain, knowing that someone higher up would drench

the dra in red ink and send it back to rework with the document

looking nothing like the original. is frustration is still prevalent

today.

I simply cannot say it more clearly—“e struggle to write comes

to an end!” e countless hours of rewriting bullets stops here.

When I was at base level, I supervised military and civilian sta members. I

struggled to write the type of performance and award bullets this book

teaches. If I had received instruction of this caliber earlier in my career, my

packages would have been stronger and my sta properly recognized. e

techniques taught in this book should be included in the curriculum for all

supervisory training programs.

—Shelly Owczarski, DAF, retired

Chief, Air Force Materiel Command

Voluntary Education Program

ose who learn this method, whether they have been a supervi-

sor for two or 22 years, express how benecial it would have been if

the techniques were accessible much earlier in their career. Some

were adamantly upset because they struggled for so long.

Since learning this process I’ve authored two major command, eight num-

bered Air Force, and over 100 wing and group level to this process. I still use

the training slides given to me by Eric to mentor the men and women in my

squadron. All I’ve received is positive feedback on how the process has

helped make them better writers. I’m thankful I’m able to share this standard

with the folks in my wing.

—CMSgt Edward Ames, USAF, retired

xvi

xvii

All supervisors incur a responsibility for counseling, conducting

feedback, and documenting performance. e techniques taught in

this book directly apply to all of these applications.

e Magic of Bullet Writing saves time by reducing edit and review

work by half or more. Productivity increases because backlogged re-

ports are transferred o your desk. Nevertheless, there is more! It also

makes your employees more productive because they’ll compose re-

ports correctly the rst time. e vicious cycle of reports going back

and forth ends.

As you begin, I would like to point out a unique aspect of the book.

Brown Bag Notes are in each chapter. ese provide a useful setup to

facilitate mentoring sessions.

I am grateful for contributing to a system that has enlightened so

many and provided such a return on investment. Please enjoy the

book in its entirety.

INTRODUCTION

Part 1

Timeless Lessons

In the movie e Matrix, Morpheus asked Neo to choose the blue pill,

which oers security and blissful ignorance, or the red pill, which

provides freedom and, perhaps painful, truth. Most of us would se-

lect the blue pill when it comes to writing. Trust me; the wool has

been pulled over our eyes through repetitive bad habit. Reading the

rst three chapters of this book is like taking the red pill. Your eyes

will be opened to the world of writing in a whole new way. Once you

know the truth you will see everything dierently aerward, just as in

the movie.

However, just seeing the truth is not enough. Aer seeing the Matrix

for what it was, Neo had to relearn everything about life. So, the trick

is to not just see anew but also to learn anew.

is book includes numerous writing tips, but the premise of the

book is to teach a technique called the “magic.” e best part—you

will apply the magic in the remaining chapters. It’s time to enter the

rabbit hole.

Chapter 1

Genesis

Let there be light.

—Genesis 1:3

While a promotion may catapult someone to supervisory status,

it does not guarantee prociency in the written word.

An organization can be transformed by teaching how to score rec-

ognition packages.

A simple three-step process identies the strengths and weak-

nesses of each bullet.

Scoring packages makes you a better writer.

Eective writing is a major part of supervisory responsibilities, yet

very little time is spent actually learning how to write eectively.

While a promotion may catapult someone to supervisor status, it

does not guarantee prociency in the written word. In 2002, to com-

bat poor writing, I taught a course entitled “How to Write Perfor-

mance Reports.” Regardless of how oen the course was taught, there

was minimal to no improvement. For 12 months the pile of blue fold-

ers holding performance reports on my desk never shrunk.

Unfortunately, many are promoted without the writing pro-

ciency needed for success.

Most supervisors only write one or two performance reports each

year. No matter how well intentioned, the majority of supervisors do

not have the experience nor the skills to write well, and the writing

course wasn’t helping. e ability to write is the sum of your entire

education, experience, and practice—as well as natural gis and tal-

ents. You cannot teach someone to become a signicantly better

writer during a one-hour seminar.

Everything changed in 2003. Out of the blue, the group superin-

tendent, 615th Air Mobility Operations Group, CMSgt Manuel

Sarmiento, directed a change to the way recognition packages were

scored. e new process included noncommissioned ocers (NCO)

and senior NCOs (SNCO), a practice commonly used across the Air

4 │ JAREN

Force today. Chief “Sam” put out a call for sharp NCOs to participate

in the upcoming board. Soon aer, replies ooded my inbox and the

rst volunteer was knocking on my door. He said, “Sergeant Jaren, I

volunteer, but I don’t know how to score awards. Is there training

available?”

I vividly recalled lessons learned during my assignment at the 15th

Air Force and knew they needed to be shared. at evening I stayed

late to write down practices learned years earlier. In the coming days,

several senior leaders—the squadron rst sergeant, MSgt Alexander

Perry; the operations superintendent, MSgt Christopher Powell; and

the operations ight chief, MSgt Anderson Aupiu—contributed ef-

fective feedback for the training seminar.

A simple three-step process identies the strengths and weaknesses

of each bullet.

e heart of the training centered on evaluating each accomplish-

ment against the levels of expected performance. e process applied

a simple three-step process to evaluate the strength and weakness of

each bullet. ese levels are explained in later chapters and form the

genesis of better writing.

A stunning breakthrough asserted itself soon aer delivering the

seminars—the blue folders began to go away. e magic began. By

“scoring” bullets against “levels” of performance, better understand-

ing and writing ensued.

I rst ran into one of Chief Jaren’s Brown Bag Lessons by happenstance. I put

it on my calendar and convinced myself I was too busy. I planned on skipping

it until my boss pointed at the clock and informed me I had somewhere to be.

ere are moments in your life where you reluctantly hear something that

ends up changing your vector in life. Military writing and frankly that aspect

of supervising seemed so transactional to me. e Chief’s system is a contin-

uum that categorizes our eorts by aligning those eorts with our resulting

impact on our people and our Air Force. e good, the bad, and the ugly all

can conform to the Action, Impact, Result model, but without the Chief ’s

system my writing skills lacked direction. is system is a commonsense ap-

proach that is ingenious in its simplicity.

—CMSgt Justin Deisch, USAF

Fast forward to the present. While advances in technology make

routing blue folders obsolete, the virtual “stack” of performance re-

ports is gone and remains o my desk! I realize this is not the only

successful method for writing performance bullets, but over the past

GENESIS │ 5

decade, these techniques allowed my organizations to be recognized

at the highest levels.

In 2012 I came across the strongest report I had ever read. e

author oers his thoughts:

Every bullet I wrote fed the notion . . . to give your best to the people who

deserve it. Bullets tend to write themselves when you realize the weight they

must bear in a person’s career.

e simplest way to cra every bullet is divide them into three distinct parts—

What . . . How . . . Result/Impact. Every bullet must begin by answering the

question “What did the individual do?” e bullet must inform the reader at

the very beginning if the individual was a member/follower in the task, a

decision-maker, or a leader/mentor.

e “How” section highlights what was done to accomplish the “What,” which

introduced the bullet. Numbers identify the accomplishment’s magnitude.

e rst word is oen a verb ending with “ed.”

Impact can be personnel, unit, base, etc., and may reach all of the way up to

the Department of Defense. Numbers are critical here. Money/time/man-

hour savings, high percentages achieved, accolades, or low failure/loss rates

are all great result/impact descriptors.

In general, put a leadership bullet with far-reaching impact in the most im-

portant “top and bottom” lines of your report. Work your way down from

there to the member/follower bullet impacts. Hopefully, you will have most,

or all, of the space lled up with higher level eects and not have to use the low

impact lines at all.

To sum it up, the magic of bullet writing starts with the right attitude. Do the

right thing for your people . . . they deserve nothing less.

—Lt Col Robert O. Stroebel, USAF, retired

Scoring packages makes you a better writer.

e magic is a three-step process that teaches you to read with a

critical eye. You will know as you write the bullet how it will be scored

and whether that score truly measures the accomplishment. You will

also learn what not to write. at is what this book is going to do—

teach you to score awards, with the second order eect of making you

a more ecient and accomplished writer.

With the genesis of bullet writing magic behind us, read on to dis-

cover how to build a better mousetrap through line-by-line scoring.

Chapter 2

A Better Mousetrap

Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to

your door.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Line-by-line scoring prevents halo and horn eects.

Line-by-line scoring saves an incredible amount of time. Interrup-

tions do not impact the outcome.

Score one line at a time for a fair and consistent approach.

Line-item scoring helps resolve tiebreakers; it reveals the strongest

and weakest parts of a package.

is chapter shows the importance of line-by-line scoring. Scoring

is integral to becoming a better writer. Let’s go back a little further to

understand how, born out of frustration, this principle built the bet-

ter mousetrap.

In 1998, as the 15th Air Force C-141 and C-17 aircra weapons

system manager, I had additional duties that included reviewing an-

nual recognition packages. ese encompassed everything from in-

dividual awards like the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force

omas N. Barnes Crew Chief of the Year to team packages like the

Air Force Maintenance Eectiveness Award.

Individual recognition packages were two pages long. With 12

nominees in dozens of categories, the process was labor-intensive

and daunting. Nevertheless, individual package work was easy com-

pared to the Maintenance Eectiveness Award. ese were 15 pages

long, highlighting a year’s worth of organizational accomplishments.

With four categories ranging from small to large units, there were

30–40 packages to rank.

My rst attempt to score 15 pages was a complete disaster. I vividly

recall a tall stack hitting my desk for just one category. To top it o,

each package was replete with statistics, dollar amounts, time savings,

and an unlimited quantity of scientic measurements to compare

competing units. One really needed to pay attention.

8 │ JAREN

e initial package took almost all morning. I intently read every

line with full attention. When the time came to assign a score, I dis-

covered the guiding instruction only required a value between six

and 10 points using half-point increments. Somehow it seemed odd

to read hundreds of lines and facts that were then to be boiled down

to a single digit between six and ten.

Line-by-line scoring prevents halo and horn eects.

Without reading the other packages, there was no context to which

one could relate a score. I had no feel for it. I remember wondering

what the right score should be. It was a pretty solid package and a

great eort captured. Aer much contemplation, I decided to score

an “8.5” to establish a baseline.

While this seemed like a good start to the process, it’s too easy to

feel good or bad about an entire package based on rst impressions.

Was “8.5” a credible score? If it “seemed” strong from the general

positive impression of words or accomplishments, the halo eect can

easily give a score too high and unearned. In contrast, one negative

bullet may drive the “horn” eect, where the entire package is scored

lower. As we will see, line-by-line scoring will prevent these eects.

Line-by-line scoring saves an incredible amount of time.

I picked up a second package but had to stop to attend the weekly

sta meeting. Next, a phone call reprioritized my morning and lunch.

By the time I resumed, I couldn’t recall everything I read on the rst

two pages and had to make a fresh start. About halfway through

again, another phone call and another meeting led to another chance

to start over. Time was slipping by. ere had to be a better way.

CMSgt omas E. Jones, the strategic airli branch chief, saw my

frustration and shared his technique. He showed me how to break the

package into small pieces which encouraged a fair and consistent ap-

proach.

As the HH-60 Program Manager in Special Operations Command, the sta

scored the major command annual awards. I had some experience; however,

like Eric Jaren at Fieenth Air Force, there was no clear direction or docu-

mented process on how to score packages. As a result, there would be dierent

winners amongst board members. With those dierences, board members

would rescore and if necessary discuss dierences. I found in those discus-

sions it was dicult for members to easily support why a particular package

was better than another. Aer relooking at the packages, I would sometimes

A BETTER MOUSETRAP │ 9

notice an accomplishment I did not remember or notice something written as

an individual accomplishment with no clear tie to the individual’s actions.

Bottom line, despite trying my very best, I was not always sure I’d gotten it

right. at was unacceptable.

To resolve this, I began using and developing the line-by-line scoring method

described in this book for three reasons. One, the scoring of packages would

oen be interrupted and by scoring each line, I wouldn’t be forced to start

over. Two, line-by-line scoring put me in a better position to discuss the mer-

its of a package if there wasn’t agreement amongst board members. And three,

most importantly, it helped to ensure I was selecting the best package.

—CMSgt omas E. Jones, USAF, retired

Now it did not matter if I was interrupted. In this system you can

resume right where scoring le o without wasted eort. is benet

alone makes the system a better mousetrap. But there’s more.

Score one line at a time for a fair and consistent approach.

An added strength of Chief Jones’s approach included standard-

ized scoring which assured fairness and consistency. Fairness in-

cluded removing the halo or horn eects as well as establishing a

standard. Consistency thrived in the integrity to a known standard

instead of going by “feeling.” Bottom line, the scoring system could be

trusted.

Chief Jones scored every bullet one line at a time. A strong accom-

plishment scored half of a point. If an accomplishment impacted be-

yond the organization, it scored one point. When it made strategic-

level impact it scored one and a half points. If the bullet was poorly

written, Chief Jones le a goose egg. When nished, he only had to

count up the points in the right margin to see which package had the

highest score, reecting the strongest accomplishments. Many num-

ber systems work; the important takeaway is to work it line-by-line.

Line scoring helps resolve tiebreakers; it reveals the strongest and

weakest parts of a package.

Another benet of line scoring is tiebreaker resolution. By divid-

ing scores into line-item pieces, board members can refer to their

tally in the event of a tie. More importantly, each can justify and dis-

cuss in detail why a given score was assigned.

is better mousetrap saved an incredible amount of time. Boards

using this process were fair and consistent; system trust was estab-

10 │ JAREN

lished and secured. Tiebreakers were resolved with condence. I used

this method for three years until the concept was integrated and im-

proved upon in the new scoring program designed for the 715th Air

Mobility Squadron. e next chapter builds on the vital necessity for

a consistent approach.

Chapter 3

A Consistent Approach

For me the challenge isn’t to be dierent but to be consistent.

—Joan Jett

Apply the system fairly and consistently, whether scoring each line

up to one point, two points, or by the use of dashes, crosses, or

circles.

Dierent boards can apply a fair and consistent process and ar-

rive at a dierent outcome.

Remove personal experience that introduces bias and, uninten-

tionally, reeks of the “good-ole boy” system, favoritism, or politics.

Consider the time of day you score. Be sure to score on the same

day and at the same time if possible. Changes in rest, nutrition,

exercise, and stress can aect consistency.

Valid results are critical in testing. No matter the scoring system, a

consistent approach gives validity and creates a fair result. Line item

scoring led the 715th Air Mobility Squadron to a signicant time sav-

ings and provided fairness. Incorporating this principle also led to

better writing through the new awards-scoring seminar.

Our award-scoring seminars gained momentum at the squadron.

Early on, only a dozen attended but numbers grew until the confer-

ence room was at maximum capacity. Later, people attended even

though they weren’t participating in a board.

People who struggled to write bullets throughout an entire career

suddenly understood.

It was as if a light switch was turned on as they walked out. Feed-

back was amazing and we kept hearing, “I get it now.” Even better, the

“scoring seminar” actually revealed writing aws. ose who strug-

gled to write bullets through an entire career suddenly understood.

We were happy as those pesky blue folder stacks magically disap-

peared from desks. at’s when more magic happened.

Aer teaching the seminar to a majority of our squadron, some-

thing very important occurred. e 715th received a disproportion-

ately high number of below-the-zone early promotions, quarterly

awards, and annual awards. You can only imagine the impact this had

12 │ JAREN

on morale. Within the principles taught in this book is the expecta-

tion to perform at a level commensurate with your grade, or above.

e group had four organizations with basically identical mis-

sions, composed of the same 20 career specialties. It should be virtu-

ally impossible to receive more awards than one or two standard de-

viations from an equal number of awards. We weren’t trying to sweep

awards. Supervisors merely composed solid packages that reected

the hard work and contributions of the Airmen serving in their work

sections. And 715th Airmen were leading, not just participating. We

were managing entire projects, not just supporting the eort.

ere was a second order eect as the entire organization stepped

up its overall level of performance. In the end, we were building lead-

ers at every level of the organization and documenting the results

better than the rest. We were proud, we had spirit, and if you were

7-1-5, you also knew what comes aer—“push-ups.”

While the overall goal of the seminar and this book is to under-

stand how to evaluate bullet writing and, through that medium, be-

come better at writing, an important underlying tenet is a consistent

approach. No matter the scoring rubric, CMSgt Dave Gilmore

summed up this principle:

Lack of standardization is a bad thing and cannot be measured while stan-

dardization provides consistency and can be measured.

—CMSgt Dave Gilmore, USAF, retired

Readers need to know that the system presented in this book is not

the only one that works. While we were building the seminar, I dis-

covered Chief Sam used a similar technique. He too scored line-by-

line, but used symbols instead of numbers.

Whether scoring each line to one point, two points or use dashes,

crosses, or circles, apply the system fairly and consistently.

When the chief saw a strong bullet, he marked a dash “-” in the

margin. If the accomplishment was signicant, he crossed the dash

with a “+.” When the accomplishment had a strategic level impact he

distinguished the line by drawing a circle “0” around the “+.” Consis-

tency was the key in this approach. Scores were then tallied to reveal

the strongest package.

Board members cannot infer, anticipate, or assume what the indi-

vidual accomplished. ey are charged to read the package. Unfortu-

nately, if an individual’s achievement was not documented fully in the

A CONSISTENT APPROACH │ 13

recognition package, the accomplishment cannot be fully evaluated.

It is not the outcome but the consistent approach that adds integrity

to the process. In the nal equation, trust matters. So what about ap-

plying the board member’s personal experience?

Personal experience introduces bias and, unintended, reeks of the

good ole’ boy system, favoritism, or politics.

Some may argue against a strict line-by-line analysis and favor us-

ing “personal experience.” Applying this may seem right at the time

but will lead down a slippery slope wrought with valid concerns over

fairness and bias. You know what they say—perception is reality. A

common example is cited by SMSgt Alan Braden:

As a Career Assistance Advisor, I’m frequently asked to score award packages

across the base because I have a broad scope on the installation. Sitting on

countless boards, I learned many write to “their audience” instead of the

reader. For example, when our Security Forces Airmen emphasize their

“TTPs” [techniques, tactics, and procedures] and “BDOC C3” [Base Defense

Operations Center, command, control, and communications] plans, I am of-

ten scratching my head on how that applies to me. While their eorts are

surely impressive, they have forgotten to write to ‘their intended audience’

which is a medic, bomb loader, etc. . . . You get the picture!

—SMSgt Alan Braden, USAF, retired

Another reason to remove personal experience subjectivity is that

it provides no value when a dispute arises. is is critically important,

so chapter 10 is dedicated to discussing the need for a fair and consis-

tent dispute process.

Dierent boards can apply a fair and consistent process and ar-

rive at a dierent outcome.

To be completely honest we must recognize that people have dif-

ferent values, beliefs, experiences, education, and backgrounds. We

do not think the same; the best part about the consistent approach is

that it accommodates this diversity. Dierent boards can apply a con-

sistent process and arrive at dierent conclusions. When this hap-

pens, both conclusions are fair.

Consider the following:

Board “A” evaluates a set of recognition packages and determines candidate #1

to be the winner. Board “B” follows the same process, but determines candi-

date #2 to be the winner. Consider the scores between the two packages are

within 1/2 of a point, virtually the same score. If both boards used a consistent

process, then both boards would be correct and fair in their outcome.

14 │ JAREN

Chief Sam explains his method:

I normally review my packages at night but the rst thing I do is to fold the

headings so that the nominee’s name is covered. Aer scoring the packages, I

will tally the scores rst thing in the morning. On some cases, I have to review

the notes I inserted while scoring line by line. e notes clarify or become

memory joggers adding the scores in the morning.

—CMSgt Manuel Sarmiento, USAF, retired

While this works for the chief, it may not work for everyone. Strive

to score on the same day and at the same time if possible. Changes in

rest, nutrition, exercise, and stress can aect consistency. For example,

if you are a morning person you may be more generous in the morning

and stingy in the evening. It doesn’t matter if you are stingy or gener-

ous; the scoring curve will be consistent if your evaluation is at the

same time of the day.

Both boards applied consistent measurement. Both boards consid-

ered every candidate and each one’s accomplishments. In following a

consistent scoring process, board results are trustworthy. Consis-

tency is practiced by removing personal experience from scoring

each accomplishment. ese principles assure a fair outcome regard-

less of the winner.

e rst three chapters capture the timeless lessons of bullet writ-

ing. We nally understood what we had created. At the end of the day

we learned that the seminar taught us to stop writing weak bullet

statements. With no more stacks of performance reports and annual

award results o the charts, the seminar produced a magical result in

creating better writers. ere was a second order eect as the entire

organization stepped up its overall level of performance. Writers

grew superior at evaluating performance and recognizing the accom-

plishments of people. Giving credit where credit is due and awarding

the right people is the cornerstone of recognizing and promoting our

greatest asset . . . our Airmen.

e Magic of Bullet Writing is a great tool, foundation, and guideline for any

organization. If used and consistently trained to newly assigned members

your organization will see an uprising of performance reports, award pack-

ages, and even general correspondence going to higher levels, staying and not

being sent back for corrections.

—James Shepherd

Former USAF technical sergeant

e next chapters dig deep into bullet formats and performance

levels to fully explain the magic of bullet writing.

Part 2

e Magic

It is much more dicult to measure nonperformance than per-

formance.

—Harold S. Geneen, American businessman

Part 2 reviews standard bullet formats with an emphasis on linking

the tactical, operational, and strategic concepts to the elements in a

bullet. Performance levels are discussed, and then demonstration is

provided regarding how to use them to interpret degrees of action,

impact, and results. Finally, steps are combined to create the magic!

It’s as easy as one, two, three.

e next three chapters will approach writing from a completely dif-

ferent angle. e intent is not to teach you a basic 101-level course on

how to write bullet statements. Consider the next three chapters an

advanced 301-level course on eective bullet writing.

While this book includes numerous writing tips, the premise is to

teach a technique called the “magic.” e best part—you can apply

the magic immediately aer reading this section.

Chapter 4

Bullet Formats

Small is the number of people who see with their eyes and think

with their minds.

—Albert Einstein

Two- and three-part bullets are essentially the same. Two-part

bullets are divided into accomplishment-impact (AI) statements.

ree-part bullets, the prevailing bullet format used today, are

divided into action-impact-result (AIR) statements.

e tactical-operational-strategic (TOS) concept connects ele-

ments well and explains why some elements do not connect well.

Bullets can be composed with any part and in any order. Readers

typically start at the beginning of the bullet; so, skilled writers po-

sition the most important elements at the beginning of the bullet.

Albert Einstein’s quote reveals that we see with our eyes what we

want to see—without thinking about what we are actually seeing. To

help think through bullet writing, we must have a process to do so.

is chapter is intended to refresh your memory on the standard bul-

let formats that are used to write packages, appraisals, and papers.

Just as a football team relies on basic plays for its success, the perfor-

mance writer relies on standard bullet formats to deliver statements

that score.

First, we will review the formatting process to make sure we are on

the same page. Next will be an introduction to the TOS concept and

how it is applied to bullet statements. Finally, examples are given to

identify and understand bullet components with the TOS concept.

Bullet Formats

Pick your poison—two-part or three-part bullets. Either one is

suitable for communicating accomplishments. Believe it or not, some

people get hung up on the precise format of a bullet. Hopefully this

chapter will explain how not to get stuck on format and to concen-

trate on content.

18 │ JAREN

roughout my career, I honed bullet writing skills by listening to NCOs

above me. At Edwards Air Force Base, I was chosen to write the unit’s Mainte-

nance Eectiveness Award along with another NCO. In part due to our ef-

forts, the squadron won the Air Force Materiel Command’s Maintenance Ef-

fectiveness Award for 2005. However, I knew I had a lot more to learn and was

always on the lookout for new ways to hone my skills. Flashing forward a few

years, I was still at Edwards on the Joint Strike Fighter Program. e base ad-

opted the consistent scoring guidelines outlined in this book. Using those

techniques helped me earn one of my Airmen a base level award and also

helped write a package for the Ten Outstanding Young Americans for 2010.

at Master Sergeant was chosen from hundreds of candidates nationwide to

make the nal list of 10!

—MSgt Casey T. Schoettmer, USAF, retired

Accomplishment-Impact Format

Air Force Handbook 33-337, e Tongue and Quill, illustrated the

two-part bullet as the standard format for documenting performance

appraisals, recognition packages, and a variety of background papers.

ese two-part bullets are divided into AI components.

e AI format succinctly documents performance and eliminates

unnecessary words that detract from the accomplishment itself. Brev-

ity is the goal. A further examination of the elements is worthwhile.

Accomplishment Element

e accomplishment element describes the behavior or action of

the individual. is critical component describes exactly what the in-

dividual did. I cannot stress this enough. A routine mistake made by

writers is not stating what the person specically did. Instead, writers

are caught in a trap of ambiguity, which only serves to detract from

the accomplishment. You will learn to quickly identify these writing

traps in chapter 8.

Impact Element

e impact element characterizes the result of the behavior. is

component is vital to relating relative importance of the action. It

gives scope and serves as the connective tissue between the action

and the result. e stronger the connection, the stronger the bullet.

Later, the TOS concept will explain this strength of connection.

BULLET FORMATS │ 19

Author’s Tip: e two-part and three-part bullets are essentially the same.

Please note the emphasized words above. Notice that Action-

Impact-Result in the two-part description corresponds exactly to the

three-part bullet. is shows that both formats are made of essen-

tially the same ingredients.

Action-Impact-Result Format

e prevalent method used today is three parts: Action-Impact-

Result. Similar to the two-part bullet, writers are driven to squeeze

everything into one line. It is unknown whom to credit for the three-

part format, but it now governs as the unocial standard. It captures

what the person did, what the action impacted, and the end result of

the action.

Action Element

e action must clearly describe the individual’s specic contribu-

tion. Without an individual’s clear action, you don’t have a bullet for

which to credit. e action should not only describe the individual’s

performance but also dene the “level” of performance. Did the

member perform a task, or was the action performed at a higher

level? Ambiguous or unclear statements make it dicult to under-

stand how much value to attribute to the overall accomplishment.

Impact Element

e impact element explains how the individual’s performance in-

uenced the next level and provides scope or inuence. It also serves

as a connector between the action and the result. e stronger the

connection between the action and result, the better the bullet. When

there is a poor connection, it is dicult to attribute the result to the

action.

Result Element

e result qualies the outcome of the individual’s eorts. is be-

comes the measuring stick and establishes the contribution’s value.

Tie the results to the big picture. If the results are strategic, then it is

important that the impact clearly connects to the individual’s eorts.

Sometimes writers skip this connection, and the jump to strategic

20 │ JAREN

level seems far-fetched. is is the perfect lead in to the Tactical-

Operational-Strategic Concept.

Tactical-Operational-Strategic Concept

e TOS concept explains why some elements do or do not con-

nect well. But what are the denitions of TOS levels? Paraphrasing

Air Force Doctrine, Volume 2 - Leadership (2015):

Tactical Level: Tactical expertise in the Air Force encompasses

chiey the unit and sub-unit levels where individuals perform

specic tasks that, in the aggregate, contribute to the execution of

operations at the operational level.

Operational Level: At this level, the tactical skills and expertise

Airmen developed earlier are employed alongside new leadership

opportunities to aect an entire theater or joint operations area.

Strategic Level: At this level, an Airman’s required competencies

transition from the integration of people with missions to lead-

ing and directing exceptionally complex and multi-tiered orga-

nizations.

e use of TOS highlights faulty writing techniques, such as when

a bullet jumps from tactical to strategic. Simply said, it is not likely for

tactical-level actions to aect strategic results when the actions do

not clearly connect. A strong connection is necessary to receive

credit. Without it, many will nd zero value and score accordingly.

TOS serves as a guide, not a rule.

TOS Model

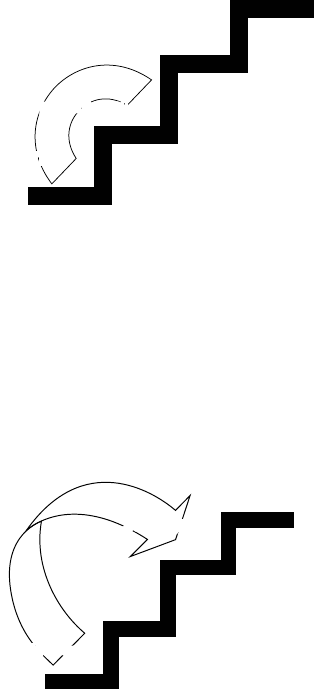

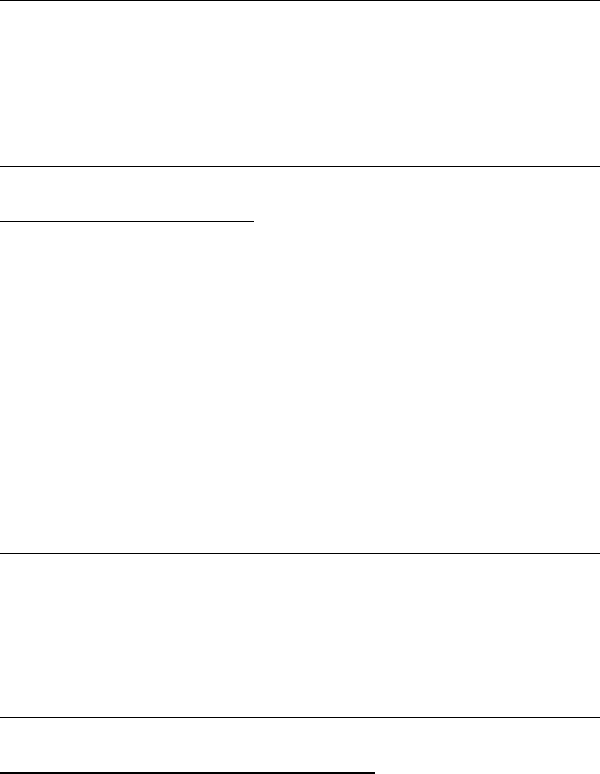

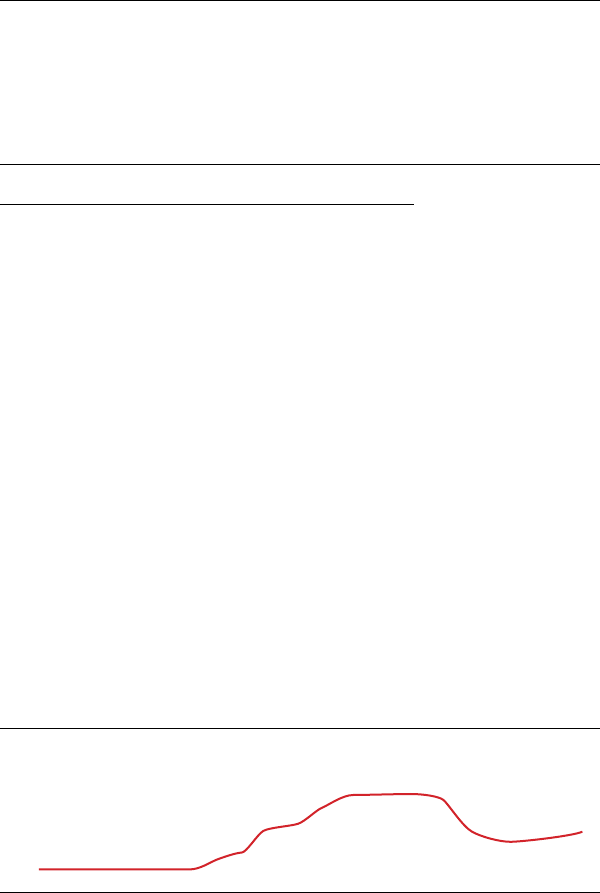

Figure 1 illustrates a strong bullet with strategic results that con-

nect well to the individual. Notice the bullet moves through each

level (action is tactical; impact is operational; and result is strategic).

is bullet would have a smooth and logical ow.

Understanding the TOS model helped me see through “farfetched” bullets

when scoring packages. Before learning this I would struggle trying to dissect

a bullet and oen rendered inappropriate value.

—CMSgt Edward Ames, USAF, retired

BULLET FORMATS │ 21

StrategicStrategic

Operational

Operational

Tactical

Tactical

Figure 1. Tactical-Operational-Strategic

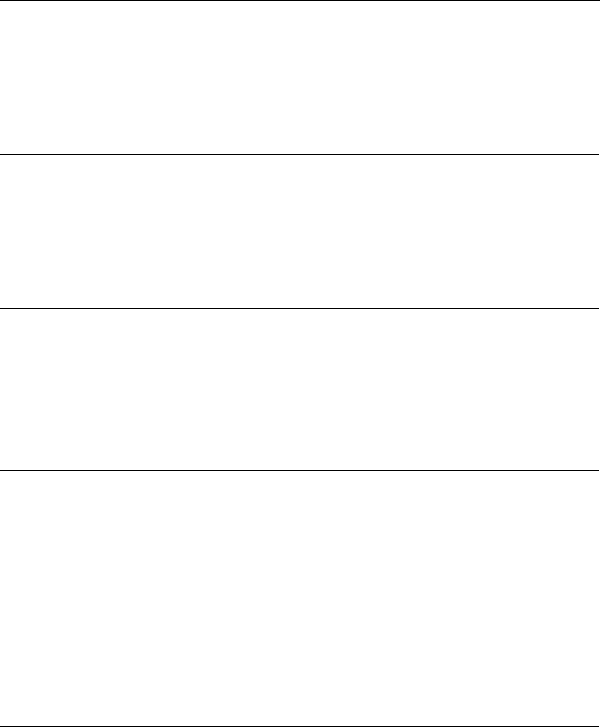

Figure 2 illustrates a bullet written at the tactical level. Notice how

each component of the bullet is at the tactical level. is bullet would

also have a logical ow.

TacticalTactical TacticalTactical

Figure 2. Tactical-Tactical-Tactical

22 │ JAREN

Figure 3 illustrates a bullet written at the operational level. is

example also has a logical ow.

OperationalOperational

Tactical

TacticalTactical

Figure 3. Tactical-Tactical-Operational

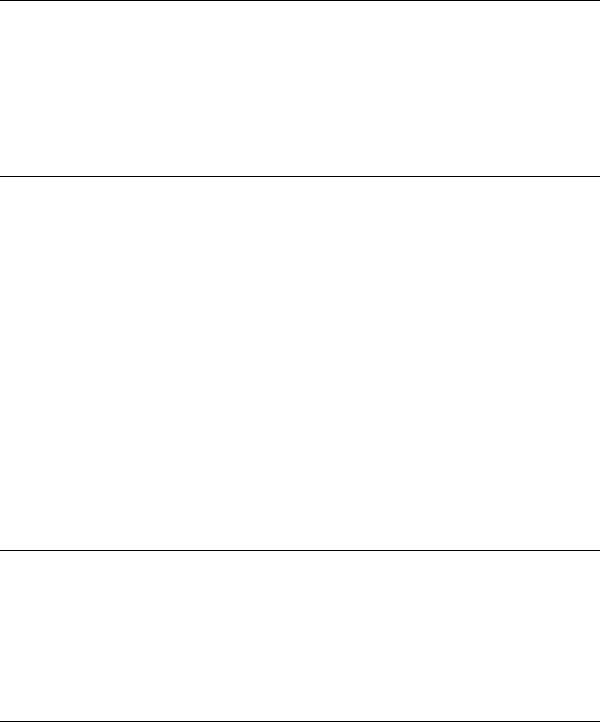

Figure 4 is a disconnected bullet. e statement starts at the tacti-

cal level, but then it skips to the strategic level. Bullets composed in

this format make a poor connection because the contributions of the

individual do not connect to the strategic results. TOS explains this as

a “bridge too far” for the eort described.

TacticalTactical

Strategic

Strategic

Tactical

Figure 4. Tactical-Tactical-Strategic

Evaluating TOS

I cannot stress how important it is to describe the connection be-

tween levels in the bullet statement. TOS is not something to literally

write out, but it is a concept to help understand the congruence of a

bullet.

BULLET FORMATS │ 23

I’ve seen this TOS issue quite a few times while scoring packages. Aer seeing

a few TOS problems on the same nominee, package credibility was lost. I re-

member being asked by the board president, a Command Chief, why I scored

the package so low. e nominee was a maintainer and a few bullets missed

that connection. Another board member, also a maintainer, agreed with my

assessment. With line by line scoring and a lack of connection, it was easy to

explain my reasoning to the board president.

—CMSgt Manuel Sarmiento, USAF, retired

e example below shows the TOS model at work with example

bullets and explanations.

Tactical Element

—Replaced tire in half job standard

Tactical

In this example a crew chief changed a tire. e action is clear; so,

readers easily recognize the tactical performance.

Operational Element

—Replaced tire in half job standard; aircra launched on time

Tactical Operational

e operational element describes how the individual’s actions

impacted the mission. e rst two elements should unite without

confusion. e crew chief changed a tire in half the normally allotted

time, which allowed the aircra to launch on time. e aircra launch

expresses the operational component. is example is very clear.

Strategic Element

—Replaced tire in half standard; aircra launched on time—

bombs struck target

Tactical Operational Strategic

e strategic element conveys the wider impact resulting from the

action and impact. Aer launching the aircra, the jet was able to ful-

ll its mission of dropping bombs on target contributing to a strategic

result. is bullet is a good example of the TOS concept following the

24 │ JAREN

tactical-operational-strategic format. e connections are logical

from the tactical through strategic spectrum.

e next examples do not connect well.

—Replaced rivets on cargo door; $2B eet serviceable—C-5As

routed supplies

Tactical Strategic Strategic

e tactical accomplishment is clear. e individual changed riv-

ets on a cargo door. e problem is that the strategic level impact and

results do not connect to the action. ese linkages need to be direct

and not casual. Evaluators typically give zero credit for this bullet be-

cause it is far-fetched. Information that explains how one individual

replacing rivets on one door impacted the entire $2 billion eet is

missing. Additionally, more information is needed to understand

how changing rivets led to supplies being delivered by multiple air-

cra (in this case it was a eet C-5As). Bottom line: if the report does

not say the individual worked on enough parts for a $2 billion eet of

aircra, he/she did not. e individual merely replaced rivets on one

door, and that is tactical level only.

Flu

Before going forward, it is critical to introduce another concept.

Some call it weak writing; others call it ambiguous writing, but the

most common term is u. When an accomplishment falls below an

expected performance level, this is considered u, which is not valu-

able for recognition or merit. Remember at least one component in

each bullet must include action. Without action, you cannot conrm

the individual’s presence. Ambiguous action will impact the overall

score much more than an ambiguous result. When the word narra-

tive picture begins with u, the contribution will not clearly connect

to the results. Many will nd zero value and score accordingly.

e owing is an example of u:

—Incredible leader; essential to PERSCO [personnel support for

contingency operations] team—250 Airmen deployed to AOR

[area of responsibility]

Fluff Fluff Operational

BULLET FORMATS │ 25

e action and impact are u, and the reader cannot decipher

what the person did. “Incredible leader” does not describe perfor-

mance. “Essential” is intangible and does not describe impact. Saying

they are does not make it so. e only tangible part is the result. Un-

fortunately, the lack of action and impact prevents the individual

from receiving credit for the result.

Here is another example where the lead-in and result are am-

biguous.

—Vital member of team; processed 2K orders—sustained AOR

mission

Fluff Operational Fluff

e important thing to remember about TOS is that members

should only be credited for action, impact, and result that can be

clearly connected. Do not be inuenced by a series of superlatives,

adverbs, or other jargon that neglects the actual performance.

Which Format Is Best?

Do not get confused if the bullet does not follow typical format-

ting. Writers can use a two-part bullet and, at other times, a three-

part bullet. Writers will even forgo punctuation marks, and the state-

ment reads more like a complete sentence. Bottom line, bullets can be

written in any format, just be sure to know which components are

present and identify the value. Regardless of format, remember to

capture the interest of the reader.

To better understand the importance of attracting and keeping the reader’s

attention, I give you this example: If watching a movie doesn’t draw you in by

the rst 15 minutes, don’t [sic] draw you in, most won’t continue to watch it.

Also, if the movie has you on the edge of your seat throughout, but the ending

really stunk, most will not recommend it to a friend. Human nature tells us if

we don’t attract the evaluator’s attention quickly and sustain it, you will not

achieve the intended results. So whichever format is best (2-part versus

3-part), I would argue whichever technique achieves this dynamic is the best.

—CMSgt James Martin, USAF, retired

26 │ JAREN

Now let’s look at examples of the basic formats to expect.

Example 1: 2-part bullet

—Changed aircra tire in 1 hour; repair returned aircra fully

mission capable

Accomplishment Impact

Example 2: 3-part bullet

—Changed aircra tire; repaired in 1 hour—aircra fully mission

capable

Action Impact Result

Example 3: Complete sentence

—Changed aircra tire in 1 hour returning the aircra to fully

mission capable

Action Impact Result

In the above examples, the same actions and results were recorded

and should receive the same value.

Alternative Formats: Reverse or Inverted for Maximum Eect

Conventional wisdom explains the standard techniques should

begin with an action element. e ensuing examples illustrate this is

not always true.

Example 1: Standard 3-part bullet

—Rewrote technical data; corrected assembly errors—avoided

minor wear

Action Impact Result

is example is a three-part bullet with standard action, impact,

and result components. No components are particularly strong, but

they are clear. Carefully observe how the structure of the bullet

changes depending on the strength of the components.

BULLET FORMATS │ 27

Example 2: Reverse 3-part bullet

—Avoided $20M damage! Rewrote technical data; corrected

safety errors

Result Action Impact

Example 2 is a reverse format. Strong writers move results to the

beginning when they are the most signicant part of the bullet. Re-

arranging the bullet ensures the $20 million cost avoidance is not

overlooked by the reader. e bottom line—do not bury informa-

tion. Engineer bullets to help readers clearly see the important parts.

One More Example Set

Example 1: Standard 2-part bullet

—Rewrote technical data to correct assembly errors; avoided

$1.6K wear

Accomplishment Impact

Example 2: Reverse 3-part bullet

—Prevented eet grounding! Rewrote technical data; avoided

$1.6K wear

Impact Action Result

In this example, the action and result are not strong but the eet-

wide impact is signicant. e bullet was rearranged so the notewor-

thy part was highlighted at the front.

Putting It All Together

Either two-part or three-part bullets are suitable to eectively

communicate performance. Furthermore, bullets can be composed

with any part in any order. Skilled writers can position the strongest

components at the front of the bullet to strengthen the odds the in-

formation will not be overlooked. Engineer the bullet so the most

28 │ JAREN

important parts will not be missed. Do not make the reader hunt for

the important information. Following these tips will ensure you make

the most persuasive environment possible for success.

Chapter 5

Performance Levels

Management is eciency in climbing the ladder of success;

leadership determines whether the ladder is leaning against the

right wall.

—Stephen Covey, American businessman/educator

Performance levels are not intended to be literal; rather they char-

acterize varying degrees of involvement.

To apply performance levels, look at each piece of the bullet sepa-

rately and assign a level to that specic component. If the compo-

nent is weak or ambiguous, assign a lower performance level or

call it u.

Break down ambiguous components. You must be able to distin-

guish between those who “walk the walk” from those who only

“talk the talk.” Determine what the person actually did.

Challenge: select a few bullets from a local award package or per-

formance report. Work with others to evaluate the bullet and

compare notes. How did you do?

Stephen Covey’s management and leadership description is very

appropriate for this chapter. Performance levels are important for

scoring and, in turn, writing. ey are dened by interpreting the

degree of action, impact, and result corresponding to the level of per-

formance recorded. Performance levels include leadership, manage-

ment, supervisory, and membership. A nonperformance bullet is

called “u.” is model is a cornerstone of the magic.

Performance Levels

Do not confuse performance levels with performance. Do not take

the denition literally. Instead, use levels to characterize varying de-

grees of action, impact, and result conveyed in the bullet. When read-

ing, you must discern the context of the word in addition to the de-

gree of its characterization.

“As leaders move through successively higher echelons in the Air

Force, they need a wider portfolio of competencies,” Air Force Doc-

trine, Volume 2 - Leadership states. Performance levels correlate with

30 │ JAREN

the development of Airmen and should reect the level commensu-

rate with rank and accomplishment. Airmen at the membership level

reect performance in competencies needed for their job. At the su-

pervisory level, Airmen are expected to perform at a higher level to

advance the organization’s responsibilities. Management and leader-

ship skills inuence the entire organization and beyond as Airmen

continue to advance.

Let me take you back to 2001 to explain the origin of performance

levels. Part of the curriculum of the Senior Noncommissioned O-

cer Academy included a discussion on motivational commitment

levels. e exercise included the relevance of three levels—member-

ship, performance, and involvement. e classroom exercise illus-

trated the higher performance and involvement levels of activity ex-

pected and how to achieve these levels.

I vividly recall the instructor lecturing how senior NCOs should

perform at a level of involvement commensurate with their rank and

grade. Periodically the instructor would say, “Hey, way to be at mem-

bership level” just to drive home the point. is was a way of dening

someone who performed a minimal task such as taking out the trash

or doing homework.

e point about the performance levels is that you need to docu-

ment (and perform) above your position or grade. Membership-level

performance likely will not separate you from your peers, and if it

does, it may separate you the wrong way.

Although there were only three com-

mitment levels described at the acad-

emy, I expanded my model to four per-

formance levels due to the importance

Air Force Instruction 36-2618, e En-

listed Force Structure, places on con-

tinuing to develop leadership and man-

agement skills. Four levels—membership,

supervisory, management, and leader-

ship—present a model that corresponds

well to rank structures.

Performance Model

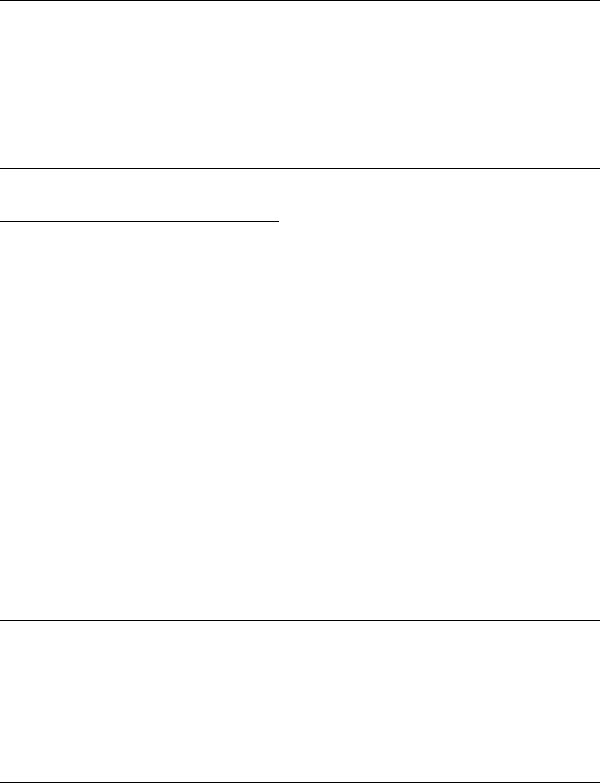

Figure 5 expresses the performance-level model. In broad brush

terms, it reects how you can go from oor sweeper to the boss. Al-

though the portrayal revolves around the military, the premise can be

Four levels—

membership,

supervisory,

management, and

leadership—present

a model that

corresponds well to

rank structures.

PERFORMANCE LEVELS │ 31

universally applied to any system. Each step in the ladder reects in-

creased responsibility, and, more important, increased expectation.

Leadership

Management

Supervisory

Membership

Figure 5. Performance-level model

Membership denes the apprentice to journeyman and the junior

ranks. e supervisory level includes journeymen, supervisors, and

NCOs. Management comprises crasmen and senior NCOs. Lastly,

and this can be dicult contextually, the leadership level describes

the contribution that anyone can perform well above expectations.

Similar to ambiguous writing, if an accomplishment is below an ex-

pected performance level, is it worth documenting on the perfor-

mance report or recognition package? e principle behind perfor-

mance levels is not what you are capable of but what is expected.

I like to use the crawl-walk-run example when explaining each performance

level. e question must be asked, “what am I being asked to do”? When per-

forming at the membership level, I’m being asked to crawl, at the supervisory

level we walk, at the management level we jog, and at the leadership level we

are running.

—CMSgt Wesley Riopel, USAF, retired

Performance Denitions

e following are basic denitions of performance levels. Please

do not get caught up in literal denitions. Levels are used incremen-

tally to denote various degrees of action, impact, and results.

32 │ JAREN

Membership

Membership-level performance infers tactical-level activities on a

small scale. ese actions are the building blocks toward larger ac-

complishments. ese eorts depict contributions of a junior Air-

man, an apprentice, or the expected daily tasking of someone higher

ranked:

• Job performance in your primary duty includes helping, assist-

ing, participating, and supporting.

• Self-improvement describes short training courses, college

classes, exams like the College-Level Examination Program

(CLEP)—things that would be considered the building blocks

toward more signicant educational accomplishments.

• Base and community involvement includes helping, assisting,

participating, and supporting.

• Mentoring includes your impact on the people in your charge.

Supervisory

Supervisory-level performance is tactical or operational in nature.

ese eorts depict actions normally accomplished by NCOs or jour-

neymen:

• Job performance includes oversight or supervision of a small

group, small team, or small program and taking charge of tacti-

cal activities.

• Self-improvement describes short in-residence or correspon-

dence courses or certications and completion of career devel-

opment courses, and completion of the Community College of

the Air Force (CCAF) degree.

• Base and community involvement includes oversight or super-

vision of small groups or small teams and organizing/leading

small-scale base and community activities.

• Mentoring includes impact on the Airmen in your charge and

expansion to those around you.

Management

Management-level is more operational in nature. ese eorts de-

pict activities normally accomplished by senior NCOs or crasmen:

PERFORMANCE LEVELS │ 33

• Job performance includes leading multiple teams, multiple pro-

grams, and/or large populations and organizing, directing, plan-

ning, and controlling large-scale projects.

• Self-improvement eorts describe signicant educational and

training milestones, long in-residence or correspondence

courses, career development course completion with outstand-

ing grades and distinction, and completion of undergraduate

degrees.

• Base and community involvement includes leading multiple

teams, multiple programs, and/or large populations and orga-

nizing, directing, planning, and controlling large-scale projects.

• Mentoring at the management level depicts activities with inu-

ence over large groups of Airmen inside and outside the organi-

zation and signicant involvement in professional development.

Leadership

Leadership-level performance depicts strategic involvement. ese

are functions expected from a leader. Remember, anyone has the

potential to perform at the leadership level:

• Job performance verbiage includes organizing, directing, plan-

ning, and supervising large programs and/or vast populations

and assuming responsibility over major operations.

• Self-improvement describes higher-level educational achieve-

ments and/or signicant in-residence courses and completion

of graduate degrees.

• Base and community involvement includes organizing, direct-

ing, planning, and supervising large base and community pro-

grams, overseeing vast operations, and assuming responsibility

over vast populations.

• Mentoring in this category demonstrates inuence over hun-

dreds of Airmen throughout the base and involvement organiz-

ing professional development panels and seminars. ese leaders

oer comments at graduations and other professional develop-

ment venues.

34 │ JAREN

Context

While anyone can demonstrate leadership, a certain level of per-

formance is expected based on your rank or position. erefore,

you should be performing at a level commensurate with or above

your position.

Oen the context of a word matters more than the word itself. For

example, look at the word leader in this bullet: “Leader! Washed cars

for the booster club.” is is u and should hold no value. e word

is inappropriately used to inuence the reader. Aer all, the individ-

ual only washed cars, which is membership level at best.

Conversely, a member of the USAF Uniform Board should carry

great value. Not many people will ever have the opportunity to par-

ticipate on the USAF Uniform Board, where they can aect Air

Force-wide change.

Bottom line: Do not get caught in a trap placing a stigma on the

denition of a word—look for context.

Apply Performance Levels to Bullets

Chapter 4 evaluated how bullets can be constructed in standard,

reverse, and inverted formats. Bullets were also divided into pieces,

giving insight into the writer’s communication style. As an evaluator,

you need to assign the appropriate level to each specic bullet com-

ponent. If the performance is strong, assign a higher performance

level. If the component is weak or ambiguous, assign a lower perfor-

mance level or call it u.

Consider the following example: “Hard-charging attitude and

dedication directly contributed to the unit winning the Air Force

Verne Orr Award.” e result seems to be leadership-level since the

award was won at the Air Force level. However, “hard-charging atti-

tude and dedication” are vague words and add no value. is u

limits credibility and hinders any bullet potential.

Upper and Lower resholds

One technique to assist in assigning a performance level is to nd

upper and lower thresholds for a particular accomplishment. For ex-

ample, an individual who instructed leadership principles to 25 stu-

dents during a one-day course might be considered leadership level.

Leadership is demonstrated at any rank and is performed at the tacti-

PERFORMANCE LEVELS │ 35

cal, operational, and strategic levels. However, rst consider the real-

istic and achievable possibilities for mentoring.

In trying to estimate what level of performance to assign, imagine

what other mentors are accomplishing. What about the individuals

who organized the following:

• Taught two subordinates how to write performance reports;

• Instructed 25 students on leadership principles during a one-

day course;

• Organized weeklong senior noncommissioned ocer profes-

sional development seminar for 50 in conjunction with a ban-

quet dinner;

• Taught two professional enhancement (PE) seminars, three Air-

men Leadership Schools (ALS), three First-Term Airmen Cen-

ter (FTAC), and organized a tour for the Reserve Ocer Train-

ing Corps (ROTC), shaping 350 future leaders.

By establishing realistic upper and lower thresholds you can com-

pare and contrast an appropriate level of performance. In this case,

what could have been perceived as leadership-level mentoring in the

rst two bullets falls short when compared to organizing a senior

NCO professional development seminar and completely pales by

comparison to the person involved in the yearlong shaping of 350

future leaders. Now the original accomplishment appears more like it

corresponds to supervisory level—“oversight or supervision of a

small group, small team, small program.” e others should appear

more like membership, management, and leadership level, respec-

tively.

e reason to mention these thresholds stems from evaluators

who profess to grade on a curve. Some purport a junior Airman or-

ganizing a car wash demonstrates leadership and thus award credit at

the leadership level. Doing this only serves to diminish the contribu-

tions of other Airmen performing at a higher level. What about the

president of the Airman’s Council who leads a yearlong committee,

conducts monthly meetings, and meets with base leadership regu-

larly? at is leadership level. Organizing a car wash is supervisory

level (oversight of a small group), and in my opinion, such eort

should not be graded on a curve. As you can see, applying proper

context helps you to identify the performance for what it is and be

condent in your choice.

36 │ JAREN

Two-Levels Concept

ere will never be a perfect system to score bullets, because you

cannot apply a checklist system to people’s values, backgrounds, ex-

perience, or interpretation of the intended message. However, you

can apply the two-levels concept. When evaluating a bullet select

“two” adjacent performance levels with the condence you have the

right choice between the two levels. For example, if a person per-

formed a certain accomplishment resulting in a $2,000,000 savings,

that should be considered a leadership-level result.

By applying the two-levels concept, practically every person should

agree that a $2,000,000 result is either a leadership or a management

level. at’s a lot of money! It should be unusual to believe a $2,000,000

result would be membership level. Every evaluator should be within

one level of each other by applying the two-levels concept.

e two-levels concept validates how two board members should

not be o by more than one level. For example, if one board member

thought the accomplishment is membership, it should be dicult for

another to perceive it as leadership. Any two board members usually

fall within one level of each other. If someone falls outside one level

repeatedly, they are oen inexperienced, occasionally parochial, or

may have a unique perspective falling outside the norm. I say the last

part to give exibility for unique and diverse thoughts, but in all hon-

esty, in 14 years of using this process, everyone who fell outside the

two levels was one of the rst two reasons.

In addition, if you nd yourself having diculties deciding on a

specic level, try using the two-levels concept. Selecting two levels